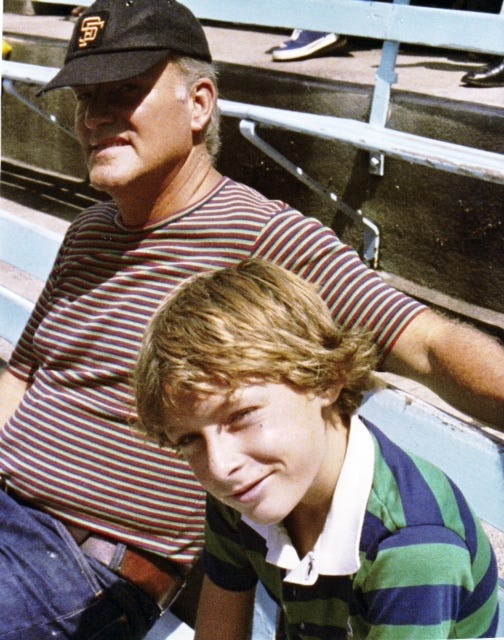

In 2016, my mom asked me to send her any photos I had of her ex-boyfriend, artist Bob Irwin, for a documentary somebody was making about him. After I found this photo of us in the stands at the LA Memorial Coliseum watching a USC football game, I wrote Irwin a letter:

Bob: My mom recently asked me for photos of you for a documentary film about you. One reminded me of the large and important role you played in my life. It is of us at a USC game during the John McKay/John Robinson era. Thanks to you, SC is the only team I follow in sports. With the one exception of my father, you were the most important male role model in my life.

Bob Irwin died last week at the age of 95, and I will always remember the day his fugly, green Cadillac Coupe de Ville glided into our Santa Monica Canyon driveway and changed my life forever. Bob Irwin did not just tell to me to follow a different path in life, he taught me, by example, how to develop the skills, tradecraft, and mindset to do it.

Bob and my mom, Joan Tewkesbury, were reacquainted in 1974 at a screening of her first film, Thieves Like Us. Shortly thereafter, they moved in together, and I went to live with my recently remarried father. For the next fifteen or so years, “Irwin” was my de facto stepfather. Relieved of all parental responsibility, Bob had the luxury to be a stern, and often merciless, but generous, teacher.

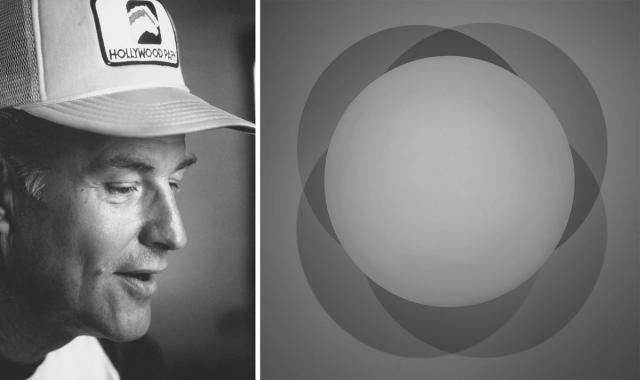

By now Irwin was well known and successful as both an artist and a teacher. He had left his paintings, disks and Venice studio behind and was moving into a new phase of his career.

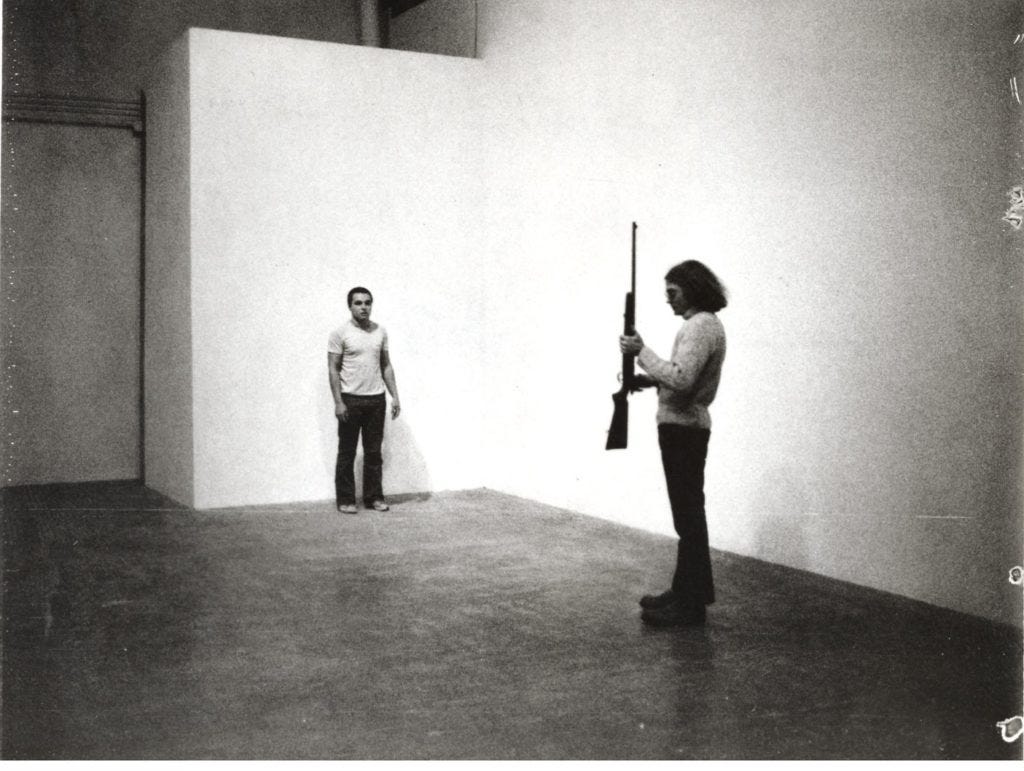

As a teacher, Bob did not want to be anyone’s mentor. Instead, he encouraged his students to be the best they could be in whatever medium they chose. The medium really didn’t matter, because the most important rule never changed: the harder you worked, the better you got, and the better you got, the luckier you got. In a short span of time, Irwin had already taught and inspired remarkably talented and diverse artists at Chouinard and UC Irvine. The Irwin alumni included: Larry Bell, Ed Ruscha, Alexis Smith, Vija Clemins, Chris Burden and others.

Bob not only looked like Socrates, he acted like him, sans disciples. Over weekly or biweekly meals at The Hamburger Hamlet, Musso and Franks, The Hungry Tiger, Monty’s, and a handful of other favorites, he would lecture me and whoever else was with us about whatever was on his mind: the latest book of philosophy he was fighting with, USC’s Rose Bowl prospects, automobiles and Angelenos, using your senses and not your brain to look at art, the moral bankruptcy of the Eastern art establishment, the art bureaucrat he was feuding with at the time, and last, but not least, whatever immediate fabrication challenges he and his assistant, Jack Brogan, were facing.

During the late 70s, Bob led a monastic life at the apartment he and my mom shared on Strathmore Drive in Westwood. He spent most of his days on and around the UCLA campus trying to bring himself up to speed on philosophy. Slowly and methodically, he read Hegel, Kant, Wittgenstein and Merleau-Ponty, and other hard books. Most afternoons, you could find him sitting outside at the Me and Me, a falafel restaurant in Westwood Village, enjoying one of his daily pleasures, a fountain Coca- Cola. He took his Coke as seriously as oenophiles take their wine and did not frequent this restaurant because of their falafels. He went there because their new coke machine had just the right ratio of syrup to soda water. Next, he would go home, don his running gear, put in a few miles on the track at UCLA’s Drake Stadium, and then take a bath. Afterwards, Bob might drink a Michelob, eat dinner, go to bed and do it again the next day. The only regular interruptions to this schedule came during the football season when the USC Trojans played, when the horses ran at Hollywood Park or Del Mar, or when he and my mom took their annual Christmas vacation to Hawaii.

Like my dad, Bob could be a real prick. He did not hesitate to put me in my place when he sensed that I was getting too full of myself and too comfortable in my Westside Manchu bubble of private beach clubs, private schools, and enervating privilege. Once when I was bragging about my standout performance in a little league game, Bob said, “Hold on a second.” He moved his chair so that he was directly in front of me, tilted his head back like he was sunbathing and said, “Go ahead, I just want to bask in your self-confidence.”

Bob always made it crystal clear that if a person wanted to pursue a career in any creative field, they needed to be able to support themselves with a side hustle that had nothing to do with their chosen creative endeavor. If you did not do this, your creative endeavor would quickly be compromised by the fickle tastes of collectors, the whims of gallery owners, the fiats of academic administrators, the censorship of timorous editors, or similar.

Bob’s side hustle was the horses. Most evenings during “the season,” he would buy the Daily Racing Form in the evening and carefully mark it up with a Flair pen. There was no “system,” just a lot of homework about horses, jockeys, track conditions, and many other floating variables. I went to the track with him a few times and it was serious business. Irwin was an extremely disciplined gambler who consistently won more than he lost.

Bob’s frugality and side hustles bought him the freedom to pursue his art career with creative and intellectual freedom. This freedom also bought him the ability to tell those he disagreed with, in no uncertain terms, they were wrong and then some. Bob did not suffer fools, did not hesitate to go for the jugular, and seemed to draw energy from his conflicts with the oppositional figures that cropped up throughout his life. When his one-time friend Billy Al Bengston began to talk shit about their dealer and greatest supporter, Irving Blum, Bob punched him. When a rich LA museum patron complained about his art, Bob said simply, “Fuck you, lady!” My favorite was the art critic Irwin took to see an elaborately customized car in some remote hamlet of LA county. When the critic refused to concede that the teenager who built the car was making aesthetic decisions that were every bit as sophisticated as any artist, Bob stopped his car, made the critic get out and left him by the side of the road. Supposedly, at a party on the East coast, Bob got in an argument about art with Jasper Johns and made him cry. God only knows how crazy Bob drove architect Richard Meier during their awkward pas de deux at the Getty Museum.

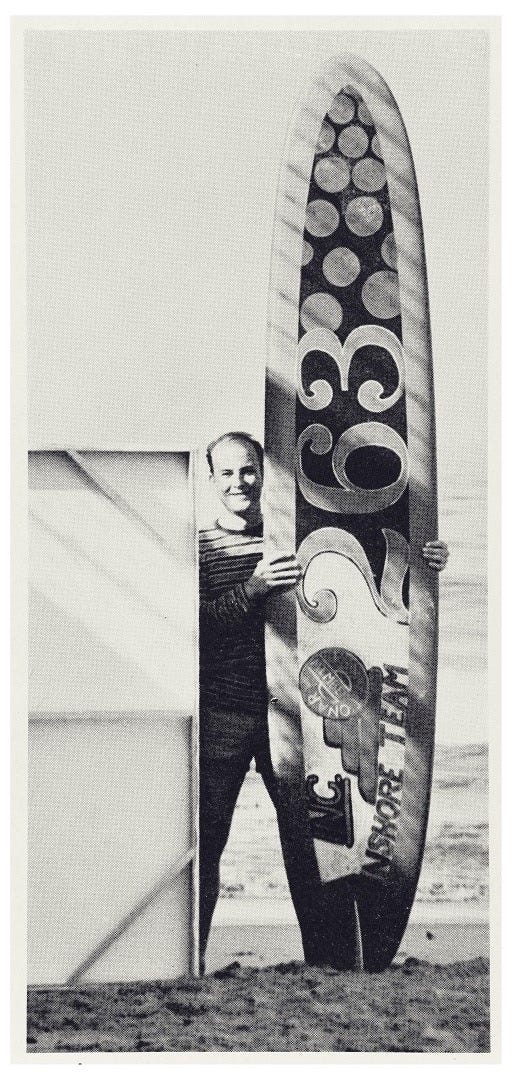

Bob also showed me that creative lives required contemplation, and this was not a group activity. To do it honestly, you could not be part of a herd, and there were much worse fates than being alone. Just because I was an athlete did not mean that I had to be “a jock,” just because I surfed didn’t mean that I had to be “a surfer,” and just because I liked to make art did not mean that I had to be “an artist.” Bob encouraged me to squeeze every hour out of every day, cross cultural lines and to be open to experiencing all the wonder that the world has to offer. His high school years were a worthy example of a Southside LA life lived. Although he played varsity football at Dorsey High School, Bob also swing danced competitively, built bitchin cars, chased beautiful girls, swam long distances in the ocean, and always, always had a job.

Bob and my mom helped me get my first real job at Melinda Wyatt’s gallery on Market Street in Venice where Bob had recently hung one of his scrims. In addition to maintaining the heaters, mopping the floors, and cleaning the bathrooms, I got to work in artist DeWain Valentine’s studio and help my mom and Joe Harvey Allen stage their one-woman play, Counter Angel. After DeWain’s artist sons, Sean and Nelson, introduced me to more artists and the lusty older women who liked them, the West Side began to look less and less interesting. In 1982, I began working as a union laborer in downtown LA. In addition to learning how to drive a forklift and use a chipping gun, I made more money as a high school student than I did decades later teaching at an Ivy League university. Although my dad was rich at the time, this money bought me the freedom to make my own decisions and do whatever I wanted. Much to my father’s dismay, what I didn’t want to do was go to college.

Instead, I worked construction in downtown LA, sold pot to the marijuana have-nots of South Central LA, saved every penny, and days before my 19th birthday in late 1983, boarded a flight to Australia. When my plane stopped over for a few hours in Honolulu, my mom and Bob were there to greet me at the gate. At an airport bar, over a beer, Bob told me how proud he was of me for setting out into the world—alone.

When I returned to LA seven months later only one thing was certain, I never wanted to live there again and I never have. Weeks before the start of the fall semester, I heard about a small, strange liberal arts college in New York that admitted students on the spot. It was called Bard. It turned out Barbara Haskell, Bob and my mom’s friend, who was also the former director of the Pasadena Art Museum and one of the true patron saints of California artists, was married to the school’s President.

Despite my low GPA and semi-disastrous high school record, Bard gave me a shot, and like Bob, also changed me forever. For the first time in my life, I became a serious student, and began to read many of the same books that I had once watched Bob sweat over.

During college, I spent most of my weekends in New York City where my mom had an apartment. Thanks to a MacArthur Genius Grant and great support from his friend and dealer Arnie Glimcher of the Pace Gallery, Bob began to gravitate east. I was an art major for my first two years of college and especially enjoyed drawing and painting. When I asked Bob to give a talk at Bard in 1985, not only did he come loaded for bear, so did some of the members of the faculty. It was at the height of the neo-expressionist movement that Bob despised and many of my professors loved.

With no notes, or script, Bob started talking as only Bob could. Halfway through the speech, he had captured most of the students’ imaginations, and this really pissed off one especially pompous member of the faculty who already didn’t like me, California artists, and Irwin, and not necessarily in that order. When the pompous professor began to express his dissenting opinions to those around him, Bob sensed it. Like a pro bass fisherman casting a big fake frog in front of a lunker largemouth, Irwin said, “And of course Morandi was one of the greatest abstract expressionists…” “What! Morandi an abstract expressionist!” the pompous professor roared from the crowd and Bob set the hook, then reeled in his prey, and expertly filleted him before our eyes.

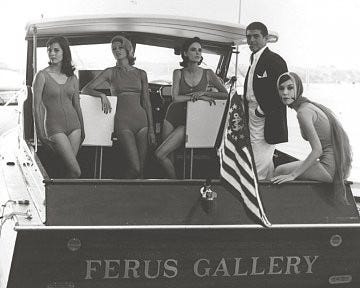

I was fortunate to be a fly on the wall at many dinners with Bob and his old friend, Irving Blum. In addition to a lighting quick wit, the Ferus Gallery founder had a tongue like a stiletto.

After one too many Barbara Rose readings in art history classes and one too many dinners listening to Irwin and Blum as they drew back the curtain on the New York City art world in the 1980s, it got harder and harder to take seriously. After all, Mary Boone was no Irving Blum, Julian Schnabel was no Bob Irwin, and for many of their rich, gullible patrons, art was just fertilizer for their real estate. In my junior year I changed my major from art to history and began writing a senior thesis that grew into my Ph.D. dissertation and first book, Law and War.

While my respect for Bob never faded, there comes a time in a young man’s life when you see your idols for the mere mortals that they and we all are. That day came for me in the spring of 1986 when I received an unexpected and urgent night time call from Bob. He was staying at my mom’s apartment in NYC and constructing a garden at Wave Hill in the Bronx.

Of course, the head garden bureaucrat hated him and of course Bob hated him back. It was the standard Irwin, fuck you-fuck you, situation. Being a bureaucrat, his nemesis did not work on the weekends, so one Saturday Bob and his loyal adjunct, Jack Brogan, attempted to push the envelope of the permissible. They brought in a piece of equipment to move some dirt, then got it, and another vehicle, stuck up to the axels in springtime mud. I told Bob not to worry and met him at Wave Hill the next morning with two four-wheel drives, tow ropes, snatch lines, and four strong friends from school. First, we freed the vehicles and then used his shovels to repair and obscure the evidence of their debacle.

My relationship with Bob Irwin ended very abruptly in 1988 after he and my mother went their separate ways. More than anything else, Bob and my mom were great friends. I believe that the support and perspective that they gave one another greatly helped each of them in their respective games. During the time they were together, my mom wrote Nashville, wrote and directed Old Boyfriends, and then pivoted to successful careers in television, theatre, and writing. Bob won Guggenheim and MacArthur grants, and even though he grew rich and world famous, he continued to make his art with the same dedication and discipline that he always had.

Over the years, I would occasionally read something about Bob or one of his projects in the press. I never thought words, Bob’s or anyone else’s, did justice to his art. Nothing excited him more than when someone looked at one of his pieces and reacted viscerally to it with their senses and not their brains, or as he used to say, “BAM! It hit’em between the eyes!”

There was some acrimony after Bob and my mom split, and I obviously sided with my mother as sons are wont to do. I did not see Irwin again until I ran into him at 72 Market Street in Venice in 1994. I had just received my doctorate and was now investigating war crimes in Cambodia, try to get my first book published and waging a one man war against the human rights industry. We were both happy to see each other and as I filled him in on my career, I could tell that he had missed me as much as I had missed him. We had shared some really good innings of our respective lives together.

I was happy that my mom encouraged me to reach out to Bob in 2016. As I have gotten older, I believe that it is important to acknowledge and pay our respects to those who have helped us along the way. Two of my greatest professors, Telford Taylor and James Shenton, both died before I had a chance to thank them. I did not want to make this mistake again, so I wrote him:

Bob….I wear many hats these days: husband/father (boys 9+11), author, history professor, martial arts instructor, ocean safety/junior lifeguards instructor, defense contractor, veteran adviser, and private investigator. I have spent much of my adult life helping others….Thanks for pushing me to see the world without restraints, but to be practical about it and, above all, always keep a day job to fund the art so that it can progress organically without outside pressure. As you probably suspected, Rob’s empire was built out of smoke and mirrors and came crashing down. Thanks to your advice, my day job saved me and my family when his empire collapsed in 2009. I have to come to California this fall and would love to catch up if you have time.

Sincerely, Peter Maguire

Bob responded back with a note, so I decided to visit him the next time that I was in California to thank him in person for all that he had taught me. A few months later, I drove down to La Jolla where my mom once lived and I had surfed as a boy. After an early morning surf at Windandsea, I headed up the hill to Bob’s house, and he greeted me warmly. Although he was still sharp as a tack, he was old, and the sand was running out of his hourglass. I sensed that he was trying to make the most of the time that he had left, and I did not want to take up too much of it.

I brought him up to speed on my life, then I thanked him for making a difference in it. Bob’s trusted assistant, Joey, was also there and they were up to their ears in a big project. I could tell that they had lots to do so I said goodbye.

When my 2021 book, Breathe, became a New York Times bestseller, I sent Bob a copy. Once again, I thanked him and told him that he, and my Jiu Jitsu teacher Rickson Gracie, who the book is about, were two of the most important teachers of my life. I think Rickson is the only teacher I have had who is as rigorous, generous, and intimidating as Bob was.

On Thursday night, after my mom told me that Irwin had died, I took my 10’2” balsa wood gun, the board I had ridden the biggest waves of my life on, and waxed it up. The next morning, my wife and I made a lei out of yellow daisies, and I went down to Wrightsville Beach to paddle it out to sea in Bob’s honor.

The waves were consistent, and it was a pain in the ass to paddle the big board through the beach break.

Just as I reached the outside and was preparing to say a few sentimental words and toss the flowers into the ocean, a big set came and caught me inside. While I managed to hang onto my board, the lei exploded and now there were clumps of bright, yellow daisy petals scattered on the surface of the greenish water. It was quite beautiful, and to borrow a term from Bob, “site specific.” I will leave it to others to talk about “minimalism,” “fetish finish,” “light and space,” “conceptualism,” “phenomenology,” and the other big words that get thrown around loosely when people talk or write about Bob’s art. I will always remember Bob Irwin as a guy from the Southside who taught me how to hustle.