I have had many great teachers in my life, but none prepared me for mi vida loca better than Rickson Gracie. It took me many years to realize that more than the ability to perform arm locks, chokes, and throws, Rickson gave me the confidence to fight for what I believe is right, speak truth to power no matter the consequences, protect those who do not have the power to protect themselves, and stay calm and improvise when plans A, B, and C fail. This, in short, is “Invisible Jiu Jitsu” and I will carry it with me until the day I die.

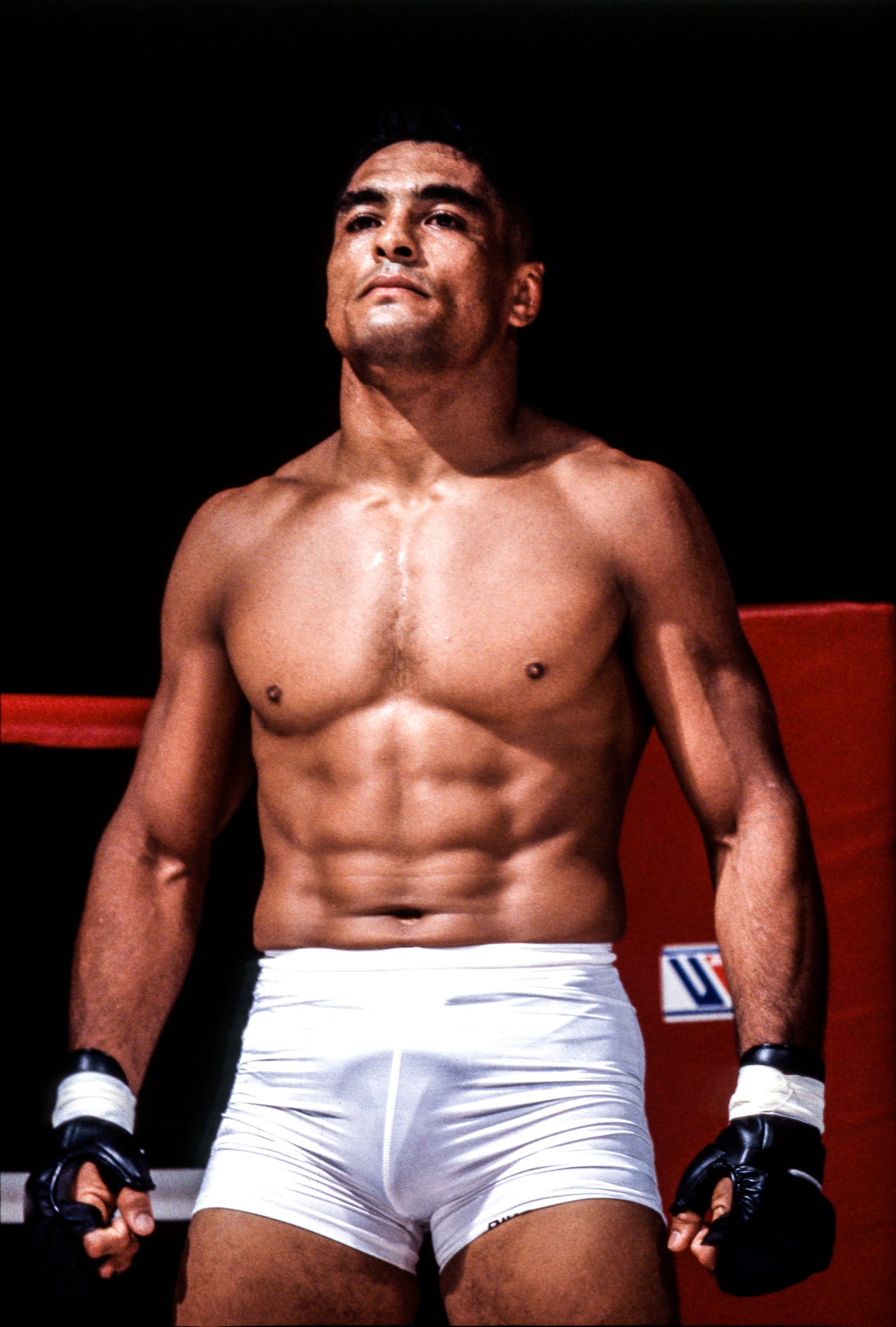

Today the phrase “Mixed Martial Arts” (MMA) evokes images of sweaty, tattooed, steroid-swollen monsters pounding each other bloody in metal cages before a global television audience. Rickson Gracie, arguably the greatest MMA fighter of the twentieth century, looks and carries himself more like a Latin American aristocrat than an MMA Übermensch. The multi billion dollar Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) empire was his family’s creation and grew out of the martial art they invented.

Gracie is regularly compared to sports greats like basketball player Michael Jordan or golfer Tiger Woods, but a more accurate analogy may be to bullfighter Manolete or dancer Rudolf Nureyev.

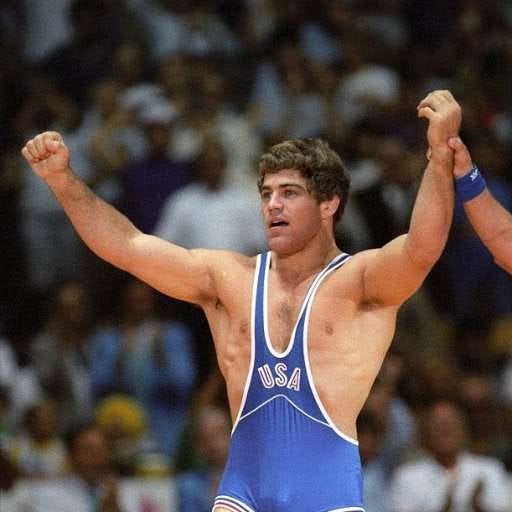

After American wrestling legend and Olympic gold medalist Mark Schultz lost twice to Gracie in a private match, he said simply, “Rickson was the best fighter I’d ever seen.”

Although Rickson Gracie’s three decades of dominance in competition Jiu Jitsu and bareknuckle vale tudo (the much tougher antecedent to MMA) fighting is astounding, even more astounding is the serenity and spiritual depth of his approach to mortal combat.

Gracie’s relationship with martial arts is a modern example of Friedrich Nietzsche’s “happy/gay science” (die fröhliche Wissenschaft), not a vindication of the UFC’s American entrepreneurial dream. His training regimen is neither solemn, nor self-important, nor exhibitionistic; rather, it is playful, flexible, and even lighthearted. When Gracie exercises, he does not count sets, much less watch the clock; instead, he tries to reach a state where he feels a balance between his mind, body, and spirit.

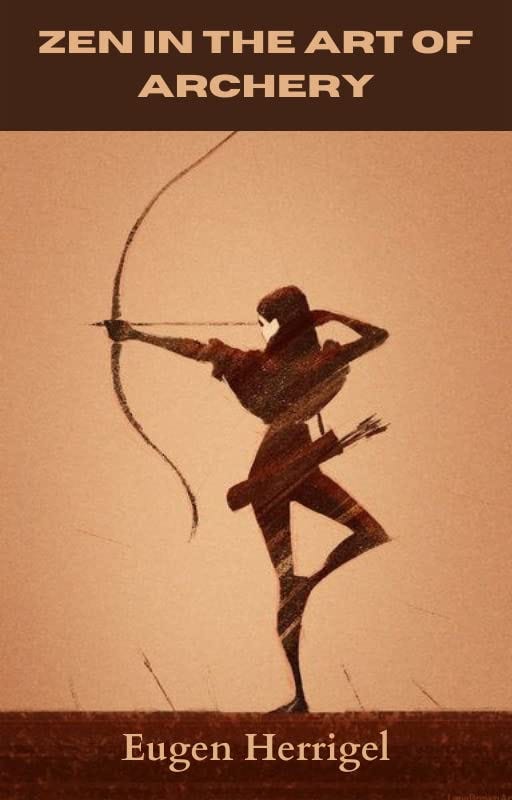

For Rickson Gracie, his art is not a sport; it is a philosophical practice. To him, the most interesting aspects of martial arts are not the techniques, but the invisible elements—the ever-changing senses of touch, weight, and momentum. His descriptions of Jiu Jitsu are reminiscent of Zen Buddhist monk Takuan Soho’s discussion of “immovable wisdom” in swordsmanship or the “unconscious control” that Eugen Herrigel wrote about in Zen in the Art of Archery.

Rickson has always used his family’s martial art as a tool to teach students about themselves, a fact I can personally attest to. When we first met at his now legendary Pico Academy in the summer of 1992, I was finishing my PhD in history at Columbia University.

For the previous two years, I had been training with martial artist John Perretti. Long before the UFC, the physically brilliant autodidact was teaching a handful of students an early version of mixed martial arts. In addition to holding several black belts in traditional martial arts, our teacher had kickboxed professionally, fought underground fights in New York City’s Chinatown, Long Island’s Native American reservations, and regularly adjudicated conflicts on the streets.

In a loft in Manhattan, Perretti taught me and a handful of others Wing Tsun kung fu, boxing, kickboxing, sadistic Gene LeBell-style grappling, and knife fighting.

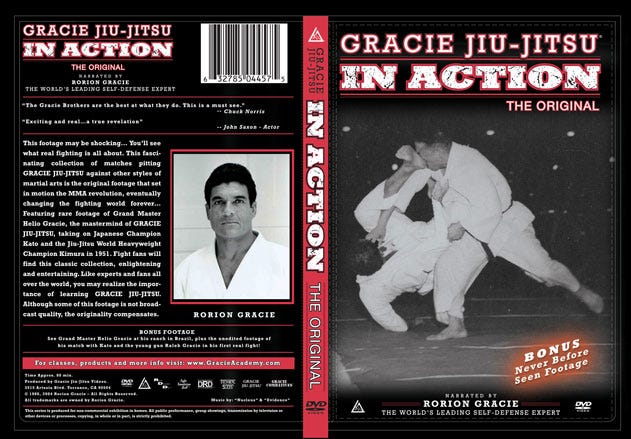

After I got my hands on a copy of Rorion Gracie’s Gracie in Action videotape in 1990, my classmates and I watched it over and over. Before the internet, all of us aspiring martial artists traded fight tapes like religious relics, and none was more prized than Gracie in Action.

Not only did it introduce us to the Gracies, the first family of Brazilian Jiu Jitsu, but the sight of skinny Brazilians tackling and choking out kickboxers who were far better than us was eye-opening. This, coupled with Rorion Gracie’s provocative mantra that “all fights end up on the ground,” planted seeds of doubt in my mind about my reliance on punching and kicking.

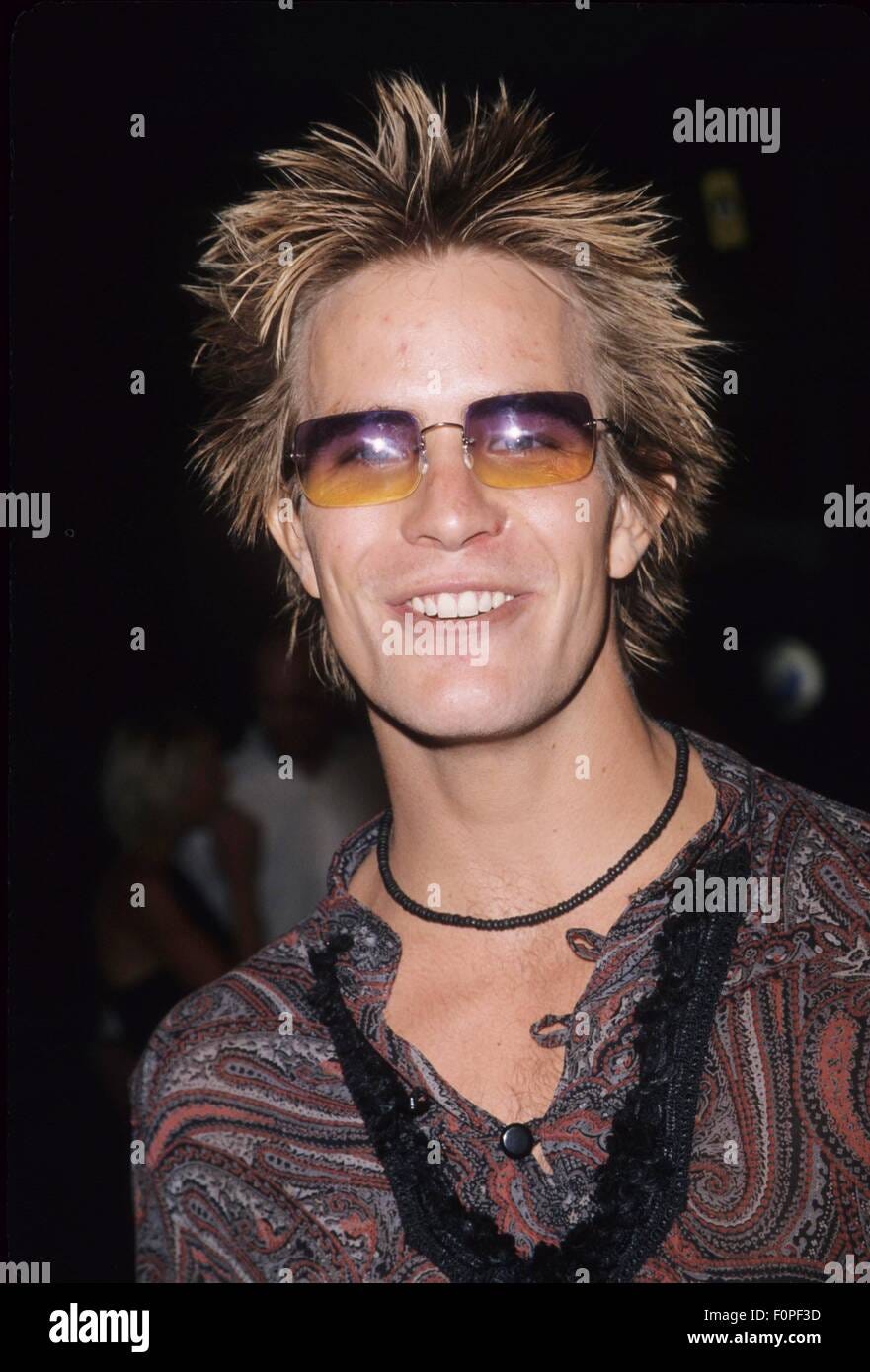

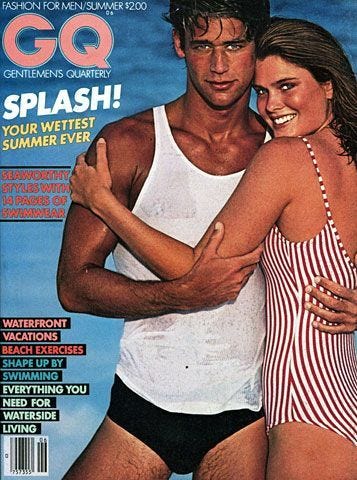

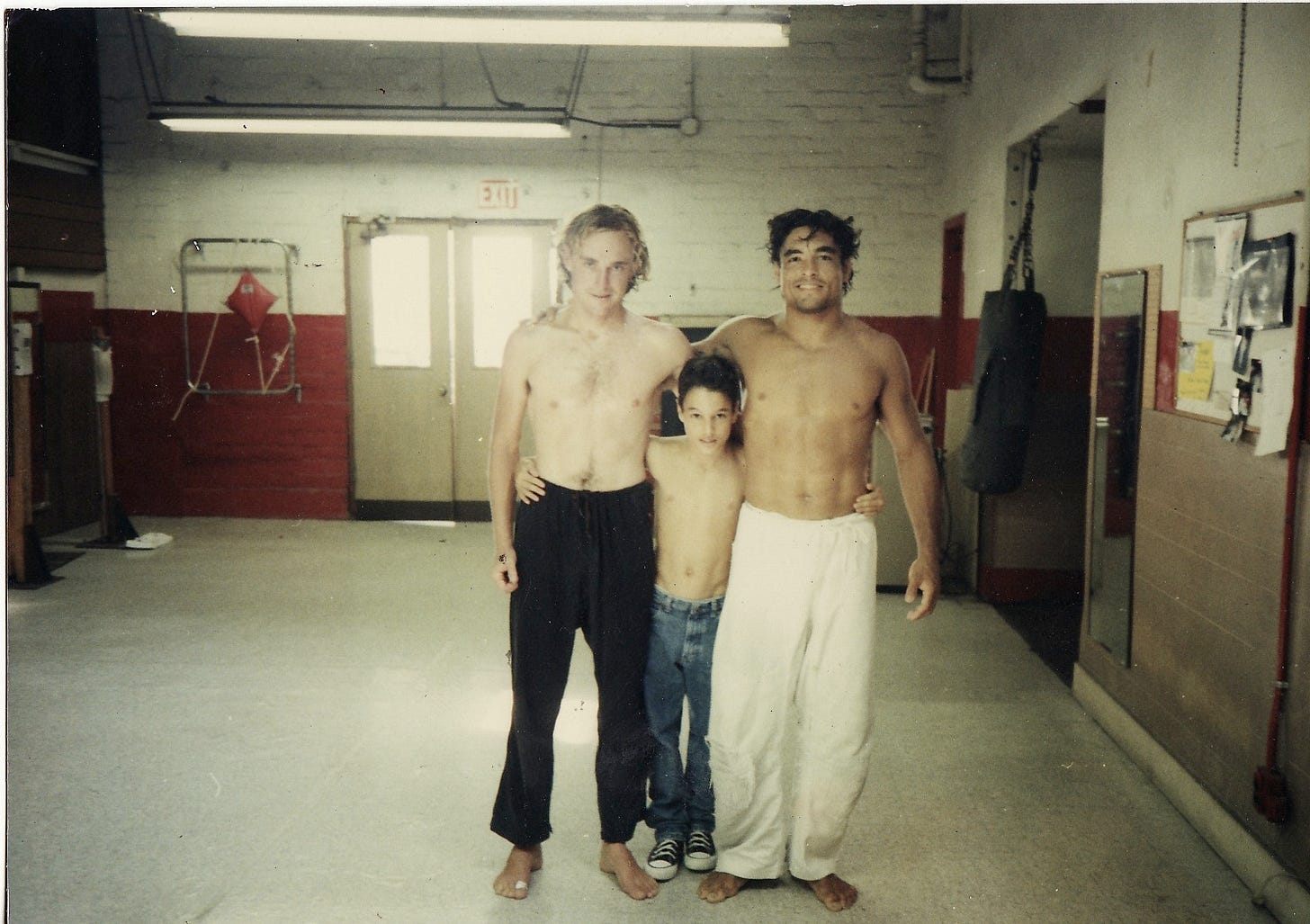

During the summer of 1992, West LA actor Ricky Hillman and 80s supermodel Todd Irvin told me that Rickson, the greatest Gracie, had opened a school on Pico Boulevard. Both were training there and could not speak highly enough of their new teacher. It didn’t matter if it was football, surfing, or volleyball, Hillman was one of the greatest natural athletes I had ever met.

Irvin was anything but a run of the mill professional handsome guy. Few knew that the tall, soft spoken man with bright blue eyes was also a skilled, former college wrestler.

I asked Todd to try to get me a private lesson with Rickson and much to my surprise, he called a day later and said, “Be there at two. His school is a little hard to find. Go east on Pico. When you hit Sepulveda, look for a fabric store on your right. Park when you see it, then walk down the driveway to the back of the building. Oh yeah,” he added as an afterthought. “They wanted to know if this is a lesson or a challenge. I told him it was just a lesson, but make sure to remind them when you get there. Lots of guys are showing up at his school to fight.”

The next day, I drove down Pico until I saw H. Rimmon Fabrics on my right, then pulled over and parked. I walked down the driveway, past an auto body shop, and saw a set of swinging, saloon-style doors, I pushed them open and entered a starkly lit, traditional Japanese karate school with a raised wooden platform, a makiwara, and an oil painting of an old Japanese karate master on the wall. While the sign said “West L.A. Karate,” something was amiss. The platform was covered with frayed green wrestling mats, and there were tan, fit Latinos sleeping on them. The West LA Karate School had rented their facility to Rickson and now this nondescript fighters’ gym was ground zero for a coming martial arts revolution that would forever change the way that the world looked at fighting.

“Can I help you?” asked the short, smiling man with a thick Brazilian accent and ghoulishly disfigured cauliflower ears, sitting at a desk and eating a late lunch. “Yes, I’m here for a private,” I replied to Rickson’s master sergeant, Luis “Limão” Heredia. “Rickson’s on his way,” he said, then returned to his lunch. I changed in the tiny locker room, and when I began to warm up by kicking the heavy bag, Limão got up from his desk, walked over, and asked casually, “Are you here for a lesson or a challenge?” His expression did not change when I replied “Lesson,” because the “Gracie Challenge” was a fact of his life.

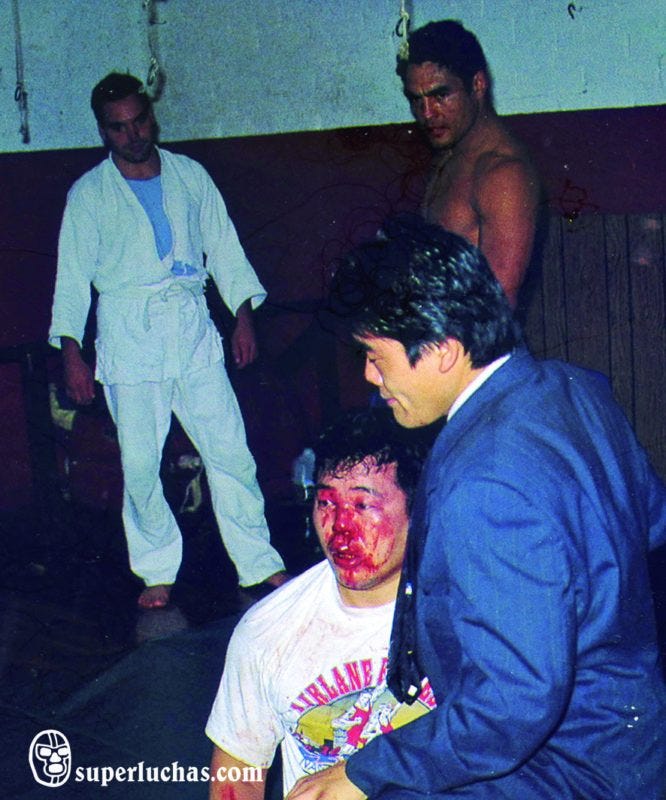

Revolutions are won on the battlefield, not in the conference room; an important part of the Gracie ethos was, and remains, the “Gracie Challenge.” To prove the effectiveness of their fighting system, the brothers openly challenged fighters from all styles to test their skills against Jiu Jitsu in as real a fight as they desired. The challenge could be a sporting affair that a tap on the ground at any time would end, but other matches were vale tudo, Portuguese for “anything goes.” In these fights, there were no gloves, or short rounds, and only two rules: no biting or eye-gouging. Unlike the UFC, headbutts, elbows, and knees on the ground were all perfectly legal.

Compared to Asian martial arts, Gracie Jiu Jitsu was informal. There were only five belts—white, blue, purple, brown, and black— and the only way to get promoted was by defeating higher belts. While Rickson would theoretically fight a challenge, a contender first had to make it through his platoon of incredibly tough blue, purple, and brown belts. The challenges were usually formal and respectful affairs but could quickly degenerate into beatings if someone broke the social contract by any form of unsportsmanlike conduct. Those who violated the social contract, I quickly became aware, were severely handled here.

Twenty minutes late, Rickson walked in, smiled at me, and apologized for his tardiness. When he shook my hand, he looked deeply into my eyes, then began to feel my shoulders, triceps, and lats, taking in nonverbal clues about me. In a nanosecond, he knew that I was as harmless to him as a gnat. Gracie was not tall, but he was extremely broad-shouldered. What struck me the most was how thick he was from his back to his chest.

Having grown accustomed to a more brutal martial arts pedagogy, my first lesson with Rickson was surprisingly calm and theoretical. First, he asked me to get into a fighting stance, then he checked my “base” by pushing, then pulling me. As the lesson went on, I was struck by how academic my first class was. Rickson’s dialectic explored physical problems that he described in terms like “base, engagement, connection, leverage, and timing.”

While grapplers had always impressed me, I detested robotic martial arts drills, whether it was kung fu, wrestling, or Judo. Gracie’s approach to fighting was the opposite. It was totally intuitive and relied as heavily on the senses as it did the brain. Rickson made a believer out of me by challenging my intellect instead of my ego. He forced me to examine, then solve, the physical problems he posed. My answers were either validated or refuted by a corporeal trial and error on the mat. Toward the end of the lesson, he asked me to try to pin him in any position I wanted, then he escaped with little or no effort. Next, he told me to try to slap him, tied me in a knot in seconds, and the only evidence of his effort was his loud, rhythmic exhalations.

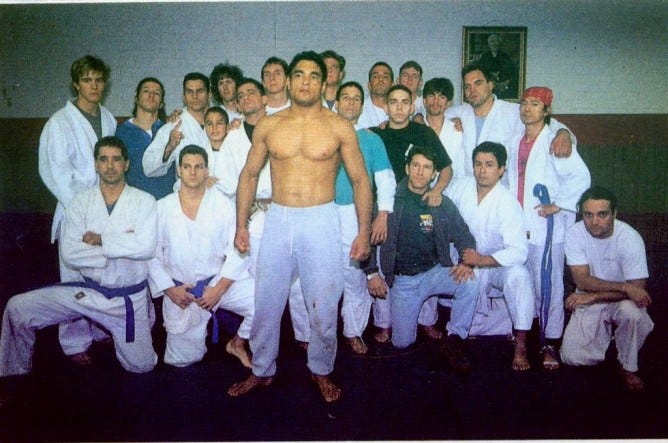

As I was getting ready to leave, Gracie’s frontline soldiers were filing in, licking their wounds, and psyching up for the evening class. Both Brazilian and American, the Pico Academy’s first generation of students were the guys who took on all challengers. The Brazilians were led by Luis Limão, Mauricio Costa, Luis Claudio, Fernando “Dentinho” Fayzano, and a revolving cast of carioca cousins and friends.

The Americans were equally impressive: Chris Saunders, Mark Ekerd, David Kama, Stephanos Miltsakis, and the dangerous teenager, Ricky “Hicky” Hillman. It was clear that each one of these guys would have taken a bullet for Rickson, so the formal and informal challenge matches were cherished opportunities to carry the Gracie flag.

Before I left the Pico Academy that day, Rickson invited me to come back and train seriously when I had more time.

I returned to LA the next summer, and instead of private lessons, I attended his 10:30 a.m. “Men’s Open Class.” Many of my classmates were professional fighters and experienced martial artists like MMA pioneer Erik Paulson and Navy SEAL hand-to-hand combat instructor Paul Vunak. My fellow white belt John Lewis would go on to fight in the UFC. While Paulson and Lewis were incredibly fit, game, and athletic fighters, much more daunting were the professional dangerous guys like the slightly fat, grizzly bear–like prison guard, the offshore oil rig roughneck whose hands were the size of catchers mitts, and the giant Navy SEAL. These men were a different species. It did not matter how slow they were or how obviously they telegraphed their moves; their size and strength allowed them to take what they wanted. Hawaiian big-wave surfer Leonard Brady best captured the mood: “At the end of my privates with Rickson Gracie at his classic Pico Academy, the group class would fill in—everyone shirts off, heavy attitudes, heavily tattooed—total prison yard at workout time.”

Socially, the class was divided into fighters that surfed, surfers that fought, and nonsurfing fighters. Almost all of the Brazilians surfed, and skill in the water was as important to them as skill on the mats. Luckily, I was a lifelong surfer and traveled the world to surf. This put me in good stead with the Brazilians, as did my access to many of California’s secret and private surf spots.

One constant at the Pico Academy that summer was the Brazilian chorus. Like a Greek chorus, it could be happy, sad, angry, or spiteful. The first time I became aware of it was when a pretty Brazilian girl burst through the academy’s swinging doors speaking loudly and excitedly in Portuguese about a bodybuilder at her gym who had talked disparagingly about her Gracie Jiu Jitsu T-shirt. Instantly, my classmates’ dark eyes narrowed, and their expressions changed. After a thirty-second cross-examination, four Brazilians, one armed with a video camera, piled into her VW Rabbit and tore out of the parking lot to find the bodybuilder. Forty-five minutes later, they returned laughing, and although they did not find their prey, they left a standing invitation for him at his gym to come visit the Pico Academy anytime.

One day Rickson told us to line up against the wall and began to talk in an honest and open way about nerves and fear. I wondered why everyone suddenly got so tense and nervous. I immediately understood when Rickson pointed to his left and said, “one hundred sixty pounds and above,” then to his right and said, “one sixty and under.” This would be my first interclass tournament. These regular informal competitions kept everybody honest about their place in the food chain. Because Rickson was the matchmaker and referee, the hierarchy at the Pico Academy was a natural one.

I drew a lanky Brazilian blue belt in my first match. I aggressively rushed in for a takedown, and after a brief scramble, we were on the ground. Although I was on top of him, he had wrapped his legs around my waist in the classic Gracie Jiu Jitsu guard. As the Brazilian grabbed my wrist with one hand and my tricep with the other, his loose hips swung. Suddenly, the back of a powerful thigh hit me in the face, found a comfortable home under my chin, and began to separate my head from my arm. Intent on not tapping out, I tried to pull away, but this only tightened his lock on my arm. As the pressure on my elbow increased, the feelings of tendons straining transformed into an internal sound—like a high-tension cable crackling and hissing just before it snaps. My elbow continued to hyperextend, and I could hear and feel things inside my elbow begin to pop one at a time—“bink-bink-bink.”

By the time I tapped, it was way too late, the damage was done, and the injury was my fault. While I tried to mask the pain, I could tell by the sickened looks on the faces of my classmates that they knew I was injured. There was a brief, harsh exchange between my opponent and the Brazilian chorus. I don’t speak Portuguese and I had no idea what the words meant, but I knew exactly what they were saying. It went something like this:

Chorus: “Why did you pop his elbow?”

Opponent: “He should have fuckin’ tapped.”

Chorus: “Sigh . . . Yes, he should have. . . .”

After the class ended, Rickson approached me and upbraided me for my haste and poor technique. Finally, he said, “Next time, tranquillo.” My arm was not broken, but my elbow was damaged, and for the next six months, every time I paddled a surfboard, I thought of the lanky Brazilian.

Other days, Rickson lined the class up against the wall and took on every single student, one after another. The matches would rarely last more than two or three minutes, but there were usually twenty to thirty of us. He made me tap with a standing armlock in less than thirty seconds.

On still other days, Luis Limão would don a comically large pair of old, worn, leather, lace-up boxing gloves and stand in the center of the mats. The exercise was a simple one: you had to tackle Limão before he punched you in the face. Given my background in Wing Tsun and kickboxing, his loopy boxing punches were easy to avoid.

For other students, however, this boxing drill was their worst nightmare. Just as boxers don’t understand the spatial relationship between two people grappling on the ground, at that time, Jiu Jitsu fighters did not box. Their sole objective was to get their opponents on the ground, where they were most at home. The worse you were at stand- up fighting, the harder you got hit. Unaccustomed to dodging blows, some of my classmates ate horrible shots, and Limão spared them neither pain nor humiliation. In our teacher’s mind, it was better to pay now, behind closed doors in the academy, not on the streets in the name of Gracie Jiu Jitsu.

The Brazilians, were impressed by my hands, especially Rickson’s eleven-year-old son Rockson. Jiu Jitsu’s crown prince was still just a skinny boy, but even then it was clear that he had the heart of a lion. He was intent on following in his grandfather’s, father’s, uncles’, and cousins’ footsteps. While I liked Rockson and he liked me, I was a native Angeleno and knew all too well what perils came with rising to every challenge in the City of Angels. Rockson was quick to identify weak members of the Pico Academy’s herd. He would innocently ask them if he could practice his choke on them. They did not suspect that such small and skinny arms could be capable of such power. Many went unconscious and woke up with a laughing child standing over them.

If the waves weren’t good, I trained three days a week. Many nights I had a hard time sleeping, because the tops of both my ears were throbbing blood blisters. Irrespective of my swollen ears, sore elbow, and bruised body, my Jiu Jitsu was getting exponentially better. In my second interclass tournament, I submitted my first opponent with a choke in less than a minute, then lost a close decision to a second, much larger opponent. After the tournament, I approached Rickson and fished for a compliment, “Better than the last tournament?” Rickson rolled his eyes and sneered, “What do you think?”

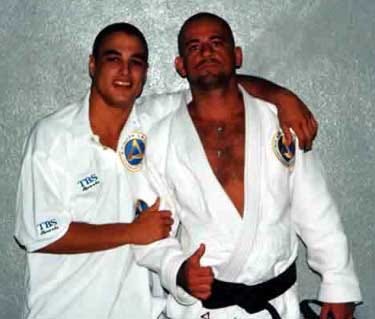

Halfway through the summer, Rickson’s brother, Royce, began coming to the Pico Academy to train with him. The rumor in the academy was that Rickson was preparing him to fight in America’s first vale tudo competition. The Ultimate Fighting Championship was largely the brainchild of the oldest Gracie brother, Rorion. Subsequently it has been claimed that Royce Gracie was selected to represent the family, because he appeared so young and unthreatening. While that might have been partially true, Rickson posed a direct threat to his older brother Rorion’s hegemony over Gracie Jiu Jitsu. Nonetheless, for a time, the Gracie brothers put their differences aside to prepare their younger brother for the first UFC. Although Royce was a formidable fighter in his own right, he was not in Rickson’s league, and this was obvious when we watched them training in the corner of the mats before our class.

Royce would do his best to endure and survive his brother’s unrelenting pressure, but that was all. When Rickson sensed that Royce was close to his breaking point, he would turn up the heat one last time, then end their match playfully. Instead of sinking a choke, he would pat Royce on the head or kiss his cheek, and all of the strain and tension of the past hour would dissipate as they joked and laughed in a way that only brothers can.

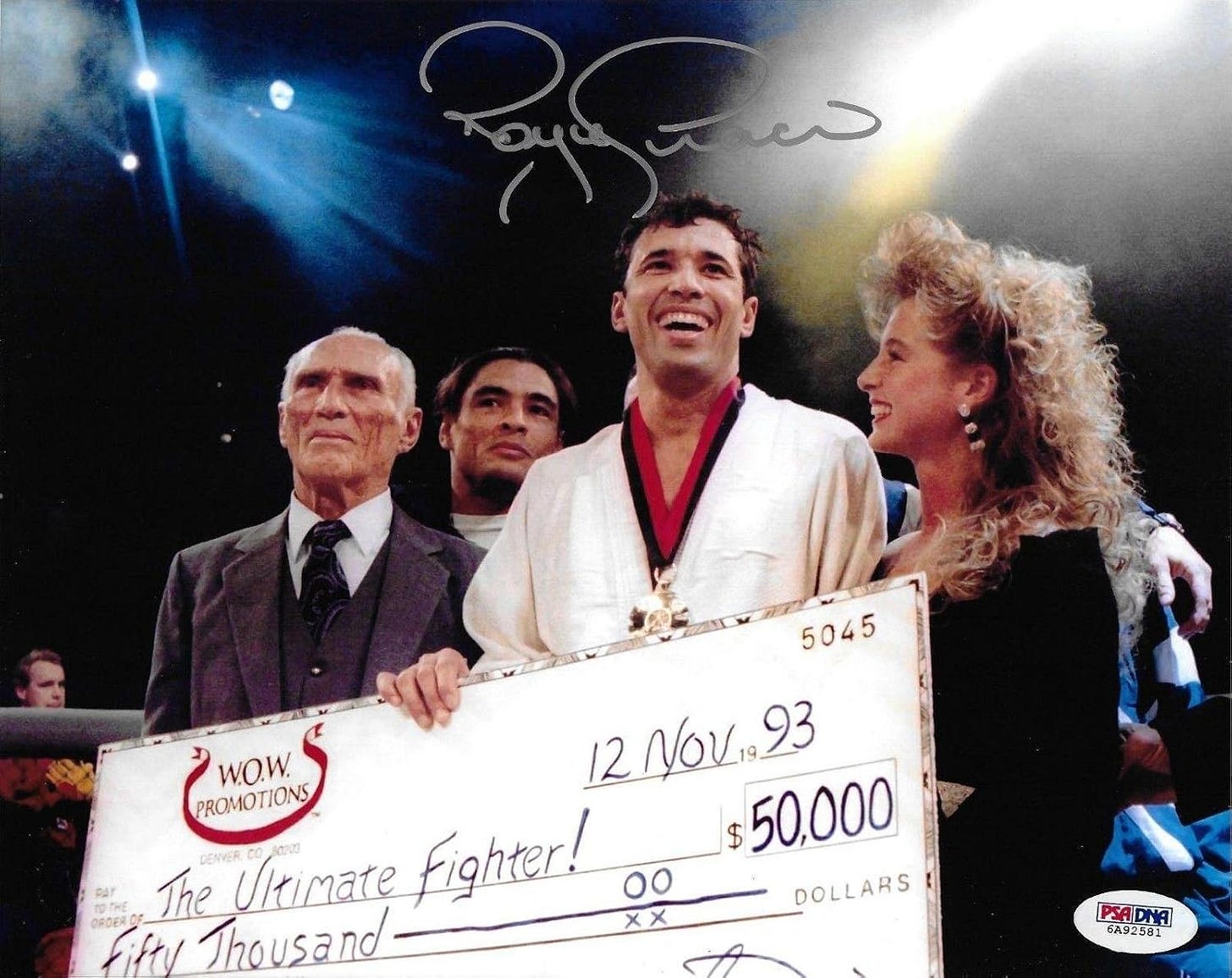

Advertised as a human cockfight in order to entice an American audience raised on Bruce Lee movies and the World Wrestling Federation, the UFC was a single-elimination tournament based on traditional Brazilian vale tudo rules. There were no gloves, no rounds, no time limits, and the only rules were no biting or eye-gouging. On November 12, 1993, 7,800 spectators attended the first UFC in Denver, Colorado, and another 86,000 paid $14.95 to watch on pay-per-view television. After Royce submitted a boxer, a wrestler, and a kickboxer to win the first tournament, the popularity of Gracie Jiu Jitsu exploded.

When I returned to the Pico Academy in December 1993, it was packed with students, and the mood was triumphant. I had just received my PhD in history from Columbia University, and even though my dissertation on the Nuremberg Trials and the laws of war had received the highest honors, I felt hollow and fraudulent, like a boxing commentator who had never stepped into the ring. I was twenty-eight, a product of the softest generation in American history, and all I knew about conflict was what I had read.

So instead of embarking on my academic career, I volunteered to work for a nonprofit in Cambodia that was documenting Khmer Rouge war crimes. When I told Rickson that I was going to the unstable, war-torn nation to investigate atrocities, he looked at me with curiosity and asked why. I told him that I wanted to find out how the Khmer Rouge had gotten away with genocide, try to hold their leaders accountable, and if nothing else, collect and preserve the evidence of their crimes. He nodded gravely, hugged me, and told me to be careful.

While I was in Asia, Royce defended his UFC title in devastating fashion—three of his four matches did not last a minute. Even though Royce was overshadowing his older brother in America, there was never any confusion about who the best fighter in the family was. In a postfight interview, Royce readily admitted, “Rickson is ten times better than me.”

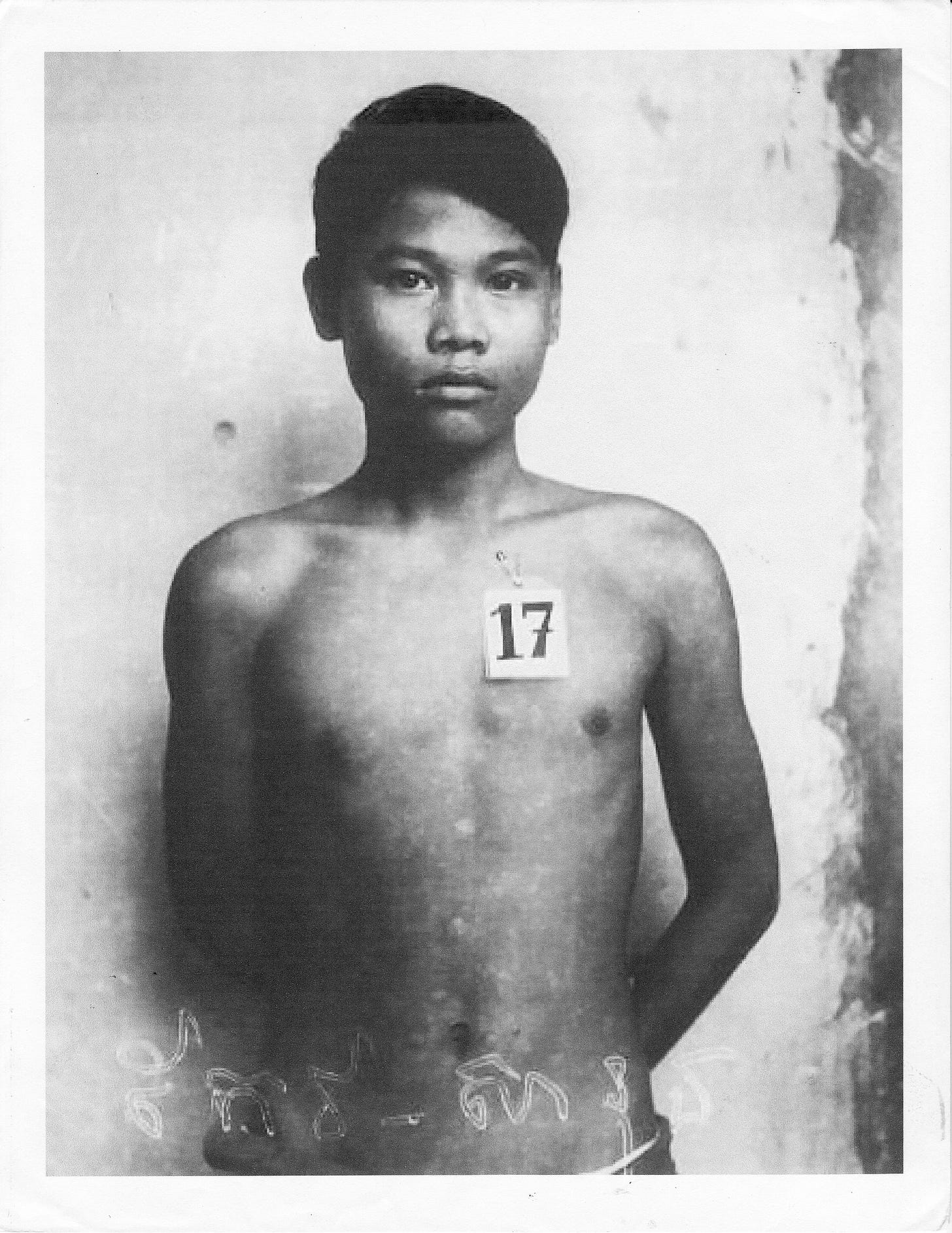

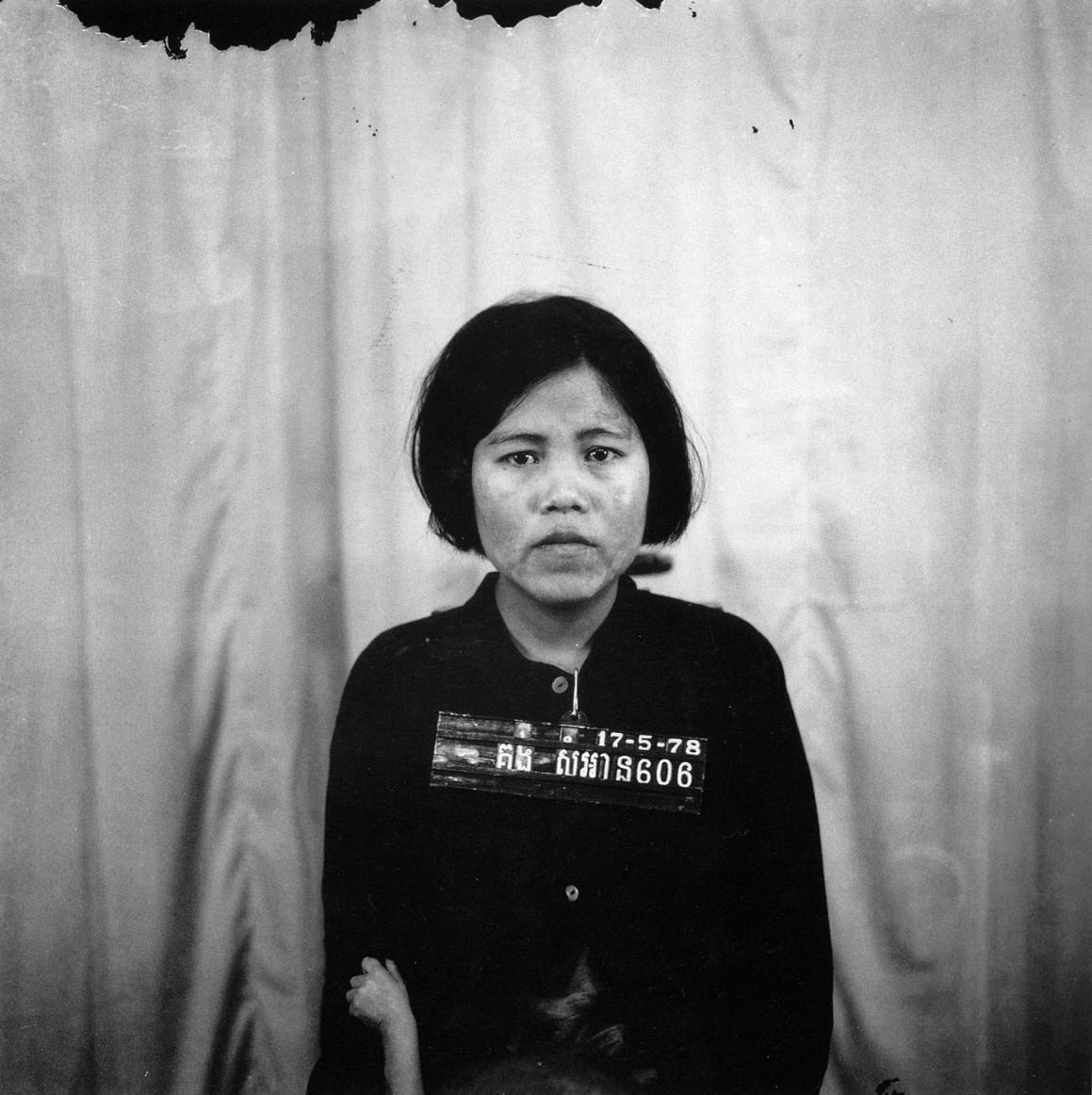

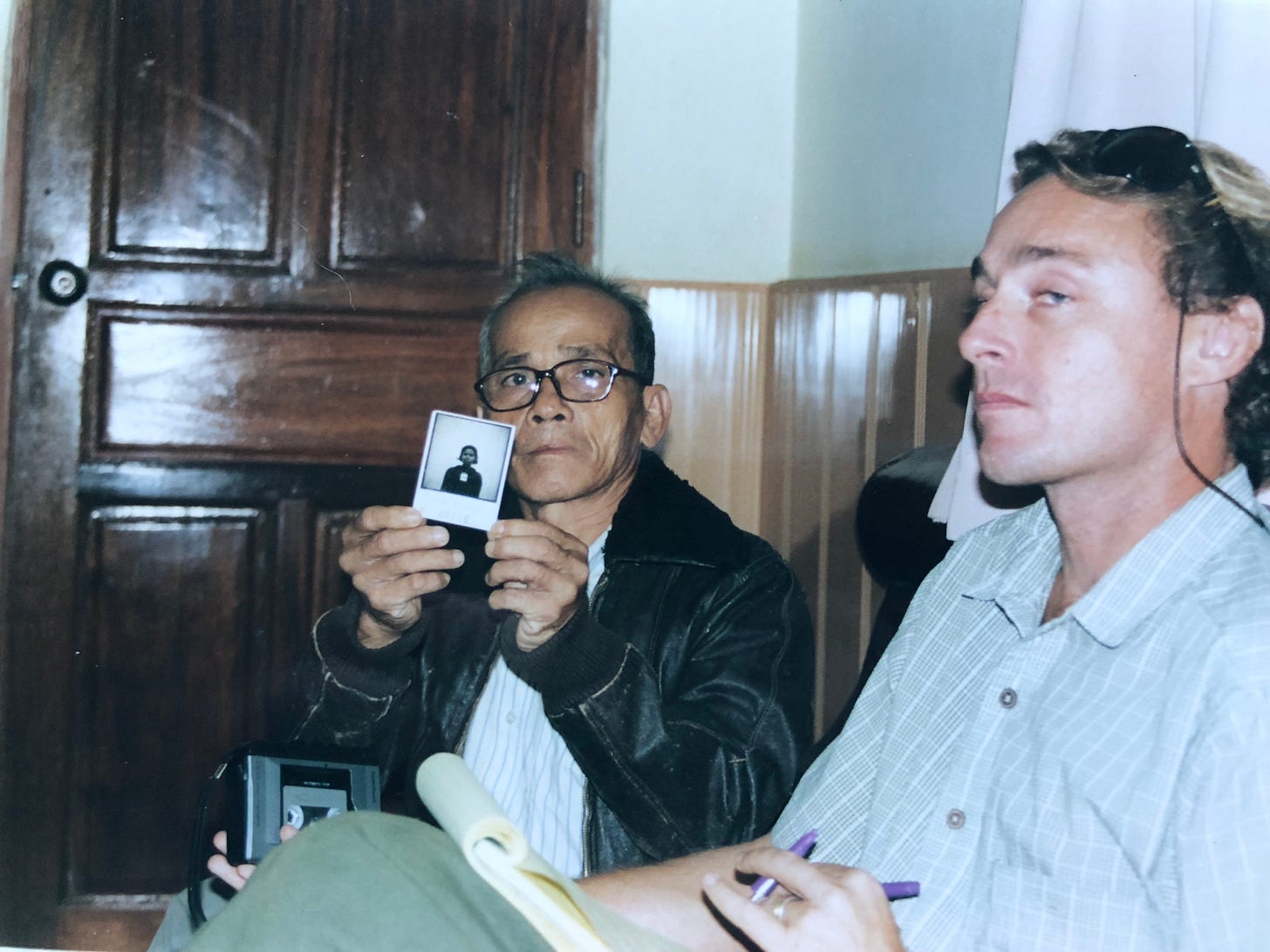

My first investigation in Cambodia centered around Tuol Sleng Prison. In 1976, the Khmer Rouge turned this former high school into a torture and interrogation center. More than twenty thousand people entered, and possibly twenty survived. Early interviews with Khmer Rouge survivors pushed me to the limits of theories of perfect justice that sounded much more convincing in university seminar rooms than in the hot, dusty backstreets of Phnom Penh.

I returned from Southeast Asia in the spring of 1994 and ran into Rickson at sunrise one morning at Malibu’s Surfrider Beach. In many ways, I was a changed man and Rickson’s life was changing just as fast as mine. He excitedly told me that he had just signed a contract to fight in Japan’s first vale tudo tournament. He said that he preferred to fight in Japan, because they had a much deeper understanding of martial arts and warrior culture than Americans.

Rickson invited me to train privately with him before I left LA. A few days later, I went to his house and brought some of the evidence that I had collected in Cambodia. Rickson winced as he looked at a photograph of a young boy with a padlock and chain around his neck, then a bare-chested young man with the number seventeen pinned through the flesh of his chest.

When he saw a sad looking mother whose child’s disembodied fist grabbed at her sleeve, he handed me back the stack of 8x10s and asked Why? So began a conversation that has continued for thirty years.

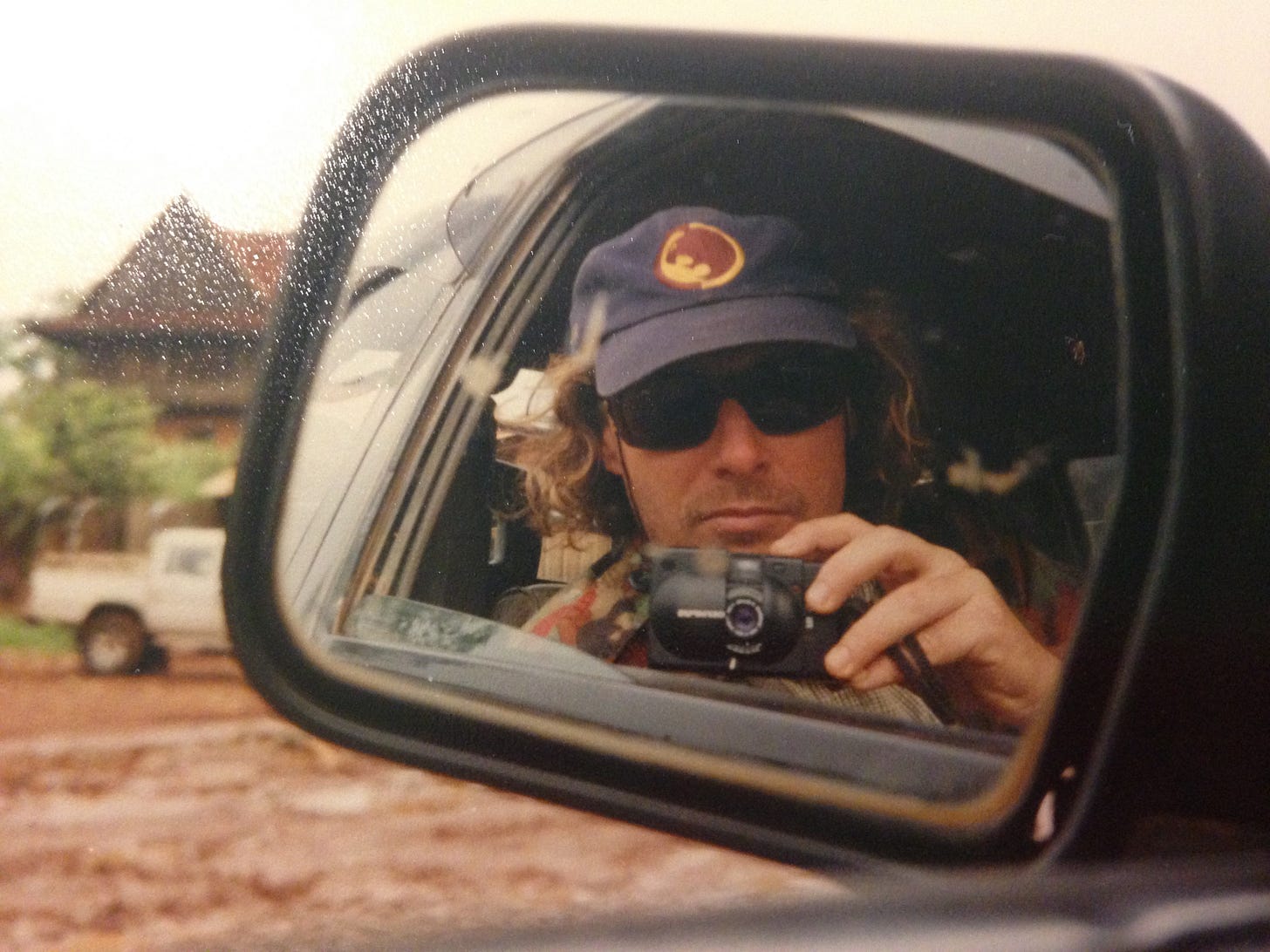

For the next decade, I devoted myself to holding the Khmer Rouge leaders accountable for their atrocities. My search for witnesses and evidence took me back to Cambodia many times, but also to Vietnam, Thailand, former East Germany, France, the Hague, Washington, D.C., and elsewhere.

In addition to investigations, I regularly briefed United Nations, US government, and human rights officials on the unlikely prospect of a Khmer Rouge war crimes trial.

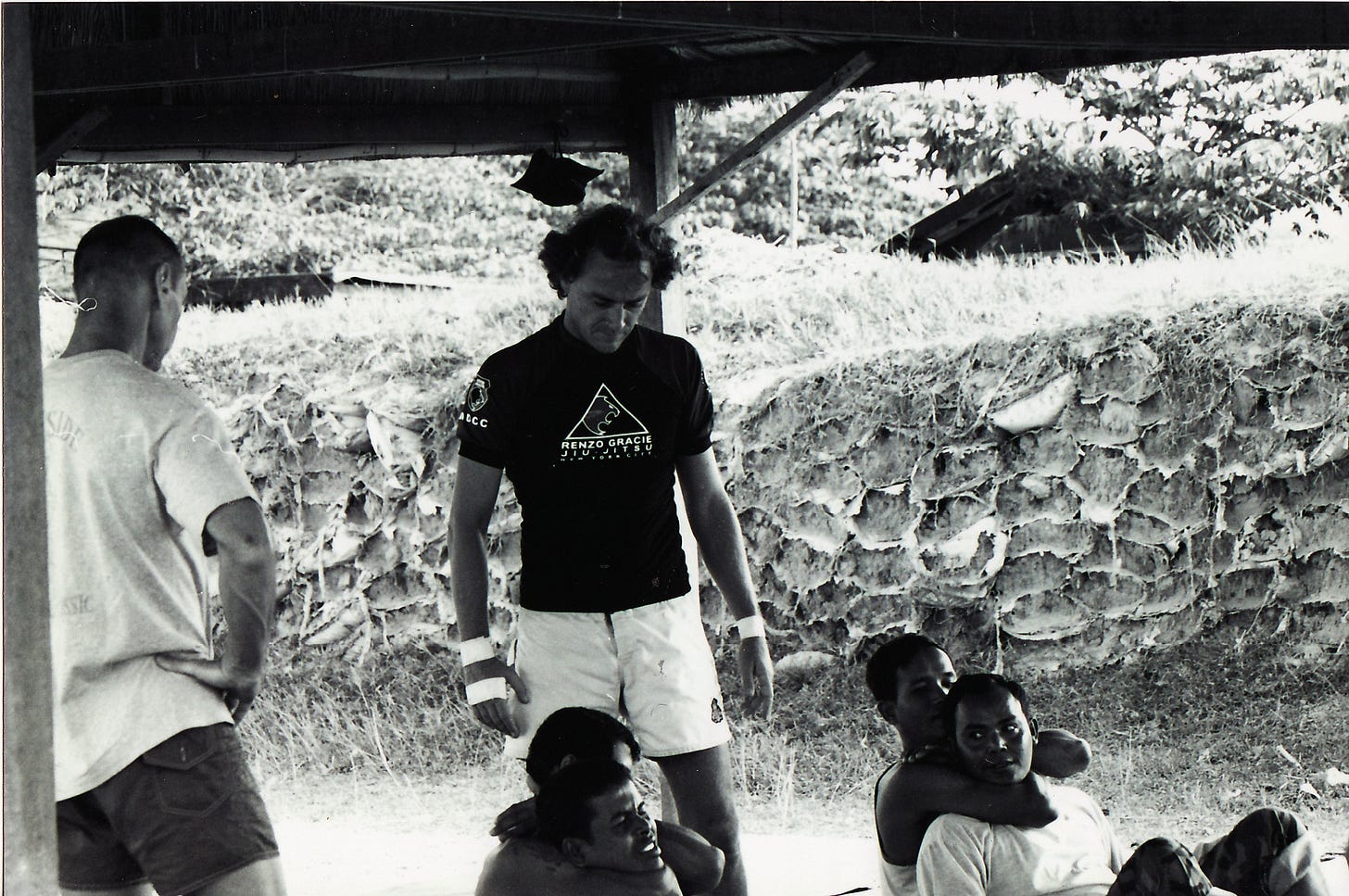

During this time, with Rickson’s blessings, I also introduced Gracie Jiu Jitsu to Cambodia, proved its efficacy, converted tough doubters into students and made lifelong friends.

When Cambodia won their first ever gold medal in the 2020 Asia Games, I was very proud that it was in Jiu Jitsu.

After many of my long and exhausting investigative trips overseas, I would clear customs at LAX, then drive straight to Rickson’s house. I would arrive unannounced, still reeking of wood smoke, dust, and stale sweat. I was eager to sigh a big breath of relief and tell my friend and teacher about my latest discoveries and martial encounters.

Often, I would find Rickson in his garage teaching a private lesson to a Jiu Jitsu legend who was in town for a tournament, or standing in a puddle of sweat, strengthening his neck with a homemade, elastic contraption, or doing breathing exercises in his unheated swimming pool [elastic contraption at 17:00 in video below].

“Fala Champion,” he would say with an always-welcoming, but slightly bemused, smile. As he hugged me, like always, he took my measure. Rickson could always sense when I had been running on minimal sleep, adrenaline, coffee, PowerBars, cigarettes, beer, and Valium for weeks on end. Before I could open my briefcase and start my show-and-tell, he would say, “Take off your boots, let’s play around a little bit.” Sometimes he gave me Gi pants to put on, but often I trained in the same dirty clothes that I had been wearing for days.

What I did not realize until many years later was that Rickson sensed my imbalance, and he was using Jiu Jitsu to slow me down, center me, and pull me back down to earth. These lessons were always long, intense, and built around a single minute detail that he sensed I was missing. He repeated the words “base,” “connection,” “leverage,” and “timing” like mantras until he was convinced that I didn’t just know these concepts, I felt them. One time he told me to stand and defend myself and then began to throw open-handed slaps at me. After I blocked and countered all of them, he said, “Yes, your hands work very well.” Then, suddenly, he threw a much more powerful haymaker. Although I blocked it, the force of his blow spun me 360 degrees. Rickson laughed and said, “But you are weak! Your hands are not connected to your base!”

Just as quickly as our impromptu classes would begin, they would end. It was usually when one of his kids saw me and wanted to hear about my latest trip. I told them about fighting off attackers on speeding motorcycles, escaping the crush of a stampeding crowd of thousands during Cambodia’s annual Water Festival, or the violent mobs that fed off the smell of fire and the sound of breaking glass during the Thai Riots of 2003.

More often than not, I wound up helping one of his kids with a school paper, dancing in the living room with his daughter Kauan, or rewriting PR copy for his then-wife, Kim.

While Rickson taught me about base, connection, and leverage, I taught him about Carl von Clausewitz, the Schlieffen Plan, the War on Terror, and the Khmer Rouge. What has made our friendship unique is that we have always given each other our unfiltered opinions, but always, through life’s triumphs, tragedies, reversals of fortunes, bestsellers, and lawsuits, stood shoulder-to-shoulder.

“You are the only person I know who can call up my dad some two days before you are in town (if that),” wrote his daughter Kaulin, on the eve of her wedding in 1999, “and get him to put on his rusty old Gi, clean out the garage, and preach his life’s philosophy.”

Initially, Comfort in Darkness was supposed to be a lifestyle guide, a victory lap after the success of our bestseller, Breathe: A Life in Flow. This book, however, took a much more serious turn in 2021.

During a class he was teaching my son, his cousin Jean Jacques Machado, martial arts legend Chris Haueter, and me, we all noticed an unmistakable tremor in Rickson’s right hand.

If nothing else, my relationship with Rickson has always been direct and honest, so I asked him about his shaking hand, and he told me that he had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

Unlike Breathe, Comfort in Darkness is much more of a collaboration than a ghostwrite. To understand Parkinson’s, I was forced to learn the biology and chemistry that I failed in school. My academic colleagues Wylan Tseh, Dylan McNamara, and Dr. Frank Snyder brought Rickson and me up to speed on the science of breathing, the physics of leverage, autophagy, neurotransmitters, synapses, dopamine, and many other aspects of the disease. Sometimes I knew more than he did; other times he refuted my academic understanding with his lived experience. As always, it was an intellectually honest give-and-take whose primary objective was to chart the best course forward to fight this debilitating disease.

Over the past two years, Rickson has shown me his faith in Invisible Jiu Jitsu, the depth of his commitment to it, and how he draws on it to fight Parkinson’s. Nothing, however, has impressed me more than the classes he holds at his small, immaculate, private Jiu Jitsu studio. Comparing the vast majority of Jiu Jitsu teachers to Rickson Gracie is like comparing a nail-gun-wielding tract house carpenter to the master Japanese Miyadaiku woodworkers who built the Temple of Hōryū-ji.

When Rickson puts on his kimono, ties his worn coral belt around his waist, and bows to the photograph of his father on the wall, he also puts his pain on the shelf for the next two hours. During these extremely intense sessions, his students’ knowledge of base, connection, leverage, weight distribution, and timing—the building blocks of invisible Jiu Jitsu—are tested.

No matter the color of their belts, every student fails in different ways. After these collective failures are examined, the real class begins as students feel and test their understanding of Jiu Jitsu’s larger concepts. There are no matches, nobody is tapping, and the atmosphere is more Socratic than martial. The lessons are stern and earnest; the lion in winter does not mince words or suffer fools. Afterward, Rickson limps off the mat and his sense of contentment and satisfaction is palpable because Jiu Jitsu’s Odysseus is always in Ithaca when he is on the mat.

Reviews

“The message of Comfort in Darkness extends way beyond mere Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. Rickson shows us what is possible when facing life’s most daunting challenges because he refuses to abandon his quest to reach the highest form of self.” — Kelly Slater, 11x world surfing champion

“Comfort in Darkness is a captivating, electrifying, and enlightening read. Rickson Gracie’s iron sight logic is as applicable to the battlefield as it is the board room. In a world where success is measured by material wealth, it is rare to find an individual who chose enlightenment instead.”—Ivan Trent, retired Navy Frogman (DEVGRU)

“Greatness tends to be known by proxy—titles, legacy, etc. Yet rarely can we study its essence, free of jaded signatures that leak meaning. Comfort in Darkness is an unflinching chronicle of brutality that peers into greatness and unveils the naked embers of the noble soul that powers it. Having lived a life so willing to die has imbued Rickson Gracie with a peace, honesty, and humility that’s palpable in every page.” — Rodney Mullen, the most successful competitive skateboarder in the sport’s history

“Rickson Gracie and I had a match in the BYU wrestling room in 1992. He made me tap out twice and told me I was the toughest guy he’d gone against. Rickson was the best fighter I’d ever seen. He still may be.” — Mark Schultz, wrestler and Olympic gold medalist

“A fluid mind-set is required to excel in both combat and life. Rickson Gracie is the embodiment of this mind-set. I don’t know of any athlete, in any sport, who can perform in ‘the zone’ or ‘the flow’ the way that Rickson Gracie did.” — José Padilha, director of Bus 174, Elite Squad, Narcos, and Entebbe

"Comfort in Darkness is an eye-opening read that sheds light on how we can better manage real-world risks and build resilience by facing our fears head on. In today’s fast-paced world, our natural, instinctual responses often get overridden or drowned out by cyber and material distractions. With so many choosing digital contact over human, it is no wonder that many feel alienated and disconnected. Rickson Gracie offers proactive ways to awaken the instincts that have kept humans alive since time immemorial. In the process, he reminds us that these instincts and the accompanying mindset are the products of conscious training and must be constantly maintained. Whether you are civilian walking alone late at night on a dark street, a commando operating behind enemy lines, or a patient in the doctor’s office receiving a terminal diagnosis, the lessons in Comfort In Darkness can help anyone face life’s challenges." —Leighton Clarke, retired British Commando

“Undefeated Jiu Jitsu champion Rickson Gracie illuminates the philosophy inherent in Jiu Jitsu, shares his vision and techniques, and explains how Jiu Jitsu can help people marshal their discipline and strengths to face any adversity in life. A moving and empowering guide.” — Karen Springen, Booklist