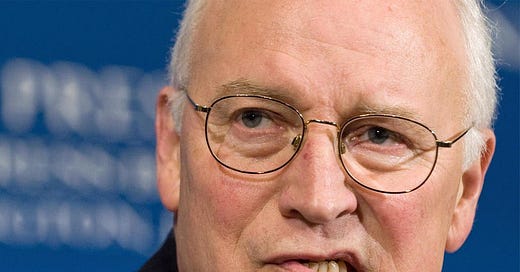

Why is Vice President Kamala Harris “proud” to have the endorsement of Dick Cheney, America’s most prominent living war criminal? I have devoted my entire professional life to legal and historical accountability for atrocities, human rights abuses, and war crimes and don’t make this accusation lightly. In my expert opinion, Cheney’s war crimes stem from his role as a principal architect of “the New American Paradigm.” “When someone shows you who they are,” Maya Angelou wrote, “believe them the first time.”1

Days after 9/11, against the advice of many of America’s military, foreign policy, and intelligence professionals, Dick Cheney convinced President Bush to replace the Hague and Geneva Conventions that govern U.S. soldiers’ battlefield conduct and treatment of POWs, with the New American Paradigm. On September 16, 2001, the Vice President unveiled his plan to millions of television viewers on Meet The Press:

“We also have to work through—sort of—the dark side, if you will. We’ve got to spend time in the shadows in the intelligence world. A lot of what needs to be done here will have to be done quietly, without any discussion, using sources and methods that are available to our intelligence agencies, if we’re going to be successful. That’s the world these folks operate in, and so it’s going to be vital for us to use any means at our disposal, basically, to achieve our objective.”

The Cheney‑led Bush administration replaced codified and customary international law with new, elastic and ever‑changing standards. Adversaries were redefined as “illegal enemy combatants,” torture became “enhanced interrogation,” and kidnapping “extraordinary rendition.”

Even though the U.S. Second Court of Appeals compared torturers to slave traders in 1980, after 9/11 only those acts that resulted in death or organ failure were considered torture. According to this new definition, not even John McCain’s treatment at the hands of the North Vietnamese met the Bush administration’s new standard.

Since 2001, I have written and spoken out against “The New American Paradigm.” I was never motivated by hatred for the United States, or sympathy for fundamentalist Islamic terrorists; in fact quite the opposite. I worried about what would become of my country if we flouted the most basic norms governing POW treatment and war crimes trials. “Although military commissions have been used throughout American history, given their uncertain historical legacy the president's decision raises as many questions as it answers,” I wrote in “Questions Hang Over Military Tribunals,” a November 21, 2001, New York Newsday op-ed. “Will ‘probative evidence’ in Bush's military tribunals include information obtained in [illegal] mock trials, as done in many of the 1945 military trials?” The answer, I would learn in late 2002, was a resounding “yes.”

After America consummated its sordid affair with Cheney’s “dark side,” brazen disregard for the laws of war was elevated to a matter of principle. By 2002, CIA paramilitary agents were clandestinely transporting suspected terrorists to top secret “black site” prisons outside the U.S. where they were tortured and interrogated. Afterwards, evidence obtained by torture was selectively leaked by the Bush administration to cabinet members, favored politicians and handpicked reporters to justify their actions.

During investigative trips to Cambodia in 2002–2003, I heard credible rumors about “Cat’s Eye,” a secret American prison in Thailand (also known as “Detention Site Green”) where CIA officials were torturing and interrogating suspected terrorists. The world would later learn that Abu Zubaydah was waterboarded there eighty-three times in August 2002 alone. After al Qaeda computer expert Abu Anas al-Libi was “rendered” to Egypt for interrogation in 2002, he claimed under duress that Iraq was training al Qaeda on the use of chemical and biological weapons. Secretary of State Colin Powell would repeat al-Libi’s lies in his infamous 2003 UN speech that justified the invasion of Iraq. Super-terrorist Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, “KSM,” confessed to masterminding thirty al Qaeda operations and even wielding the knife that decapitated Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl after months of torture, interrogation and isolation.

In short order, American policymakers, pundits, and academics attempted to rationalize the use of torture based largely on the “ticking time bomb” scenarios of television supersleuth Jack Bauer.

There was, however, one problem: evidence obtained by torture is not reliable. A 2014 Senate Intelligence Committee report concluded that Abu Zubaydah provided no new or significant information. Even worse, the same committee concluded that “the CIA's use of its enhanced interrogation techniques was not an effective means of acquiring intelligence or gaining cooperation from detainees.”

Nonetheless, the Bush administration loudly declared the New American Paradigm a great success. Over the course of the next decade, fifty-four foreign governments aided and abetted America’s torture and interrogation efforts. Some hosted CIA black sites, others captured and transported suspected terrorists, and still others turned a blind eye when their domestic airports and airspace were used to transport prisoners secretly.3

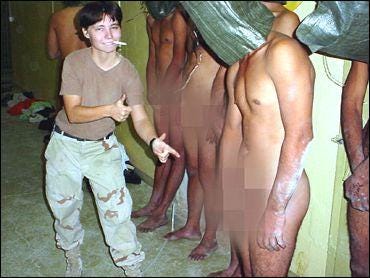

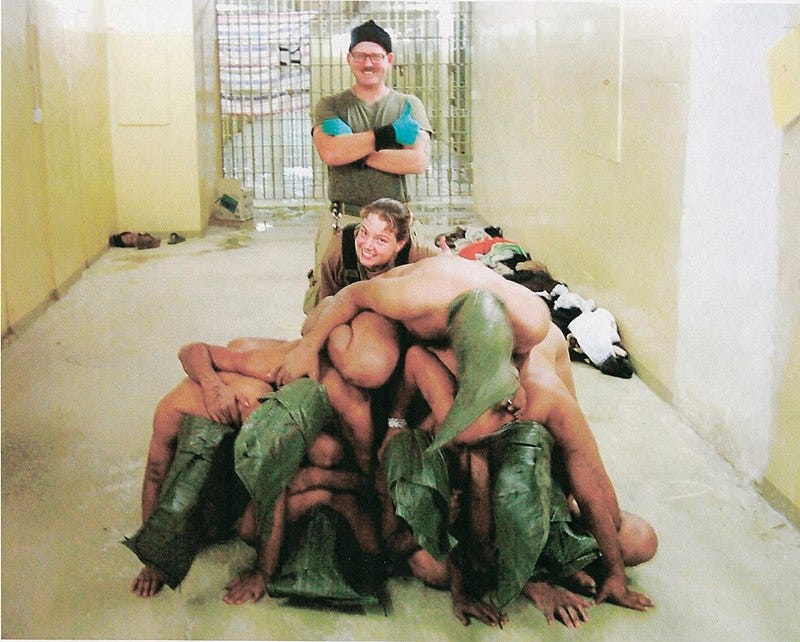

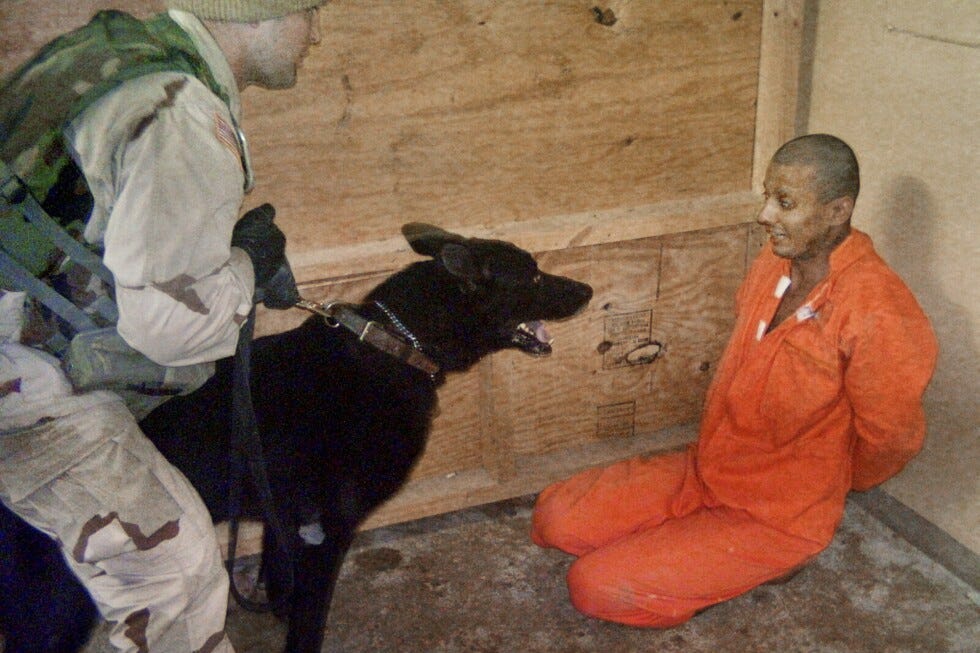

By the time the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, extraordinary rendition, secret prisons, indefinite detention of American citizens, domestic espionage, and “watchlists” were all accepted as facts of life by a stunned and submissive American public who had the luxury of viewing the havoc wrought in their name from afar. This arm’s-length relationship, however, was shattered in 2004 when Army General Anthony Taguba’s report on prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib was leaked to investigative reporter Seymour Hersh. Bin Laden himself could not have staged a more successful propaganda coup as photographs of smiling, fresh-faced American girls leading naked Iraqi men on leashes flashed around the world in seconds.

One senior policymaker described the perpetrators to me at the time as “the seven soldiers who lost the war.”

The Taguba Report exposed to the world that not just the New American Paradigm, but also “torture’s perverse pathology,” had taken root. Historian Alfred McCoy would later make the important and overlooked point that torture doesn’t just fail to provide reliable intelligence, it also “leads to both the uncontrolled proliferation of the practice and long-term damage to the perpetrator society.”

In just three short years, America’s use of torture spread from a handful of CIA agents and military psychiatrists to common Army reservists and unaccountable “defense contractors.”

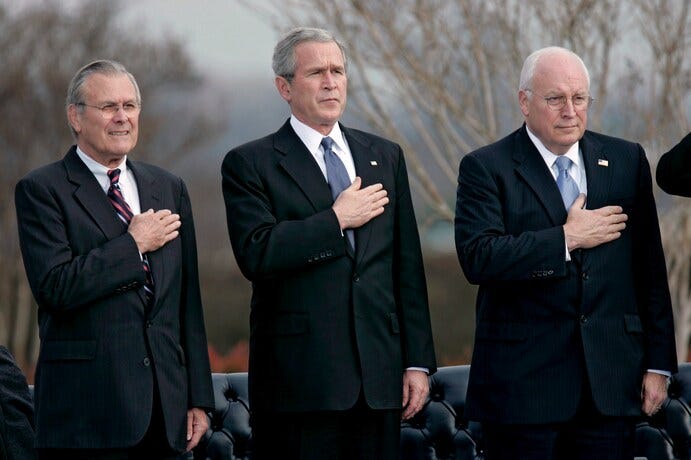

Equally important, America, according to Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s own metrics, was now losing the Global War on Terror (“Are we capturing, killing, or deterring and dissuading more terrorists every day than the madrassas and the radical clerics are recruiting, training, and deploying against us?”).

Overnight, the land of the free and home of the brave had been transformed into the land of the surveilled and home of the scared. Snitches, not truthtellers, were venerated and a bovine body politic passively accepted the Patriot Act’s unconstitutional overreach, the alphabet soup of new three-letter government agencies whose cyber gaze was now focused on American citizens, and the kangaroo courts that did their bidding. After all, “if you’ve haven’t done anything wrong, you’ve got nothing to be afraid of.”

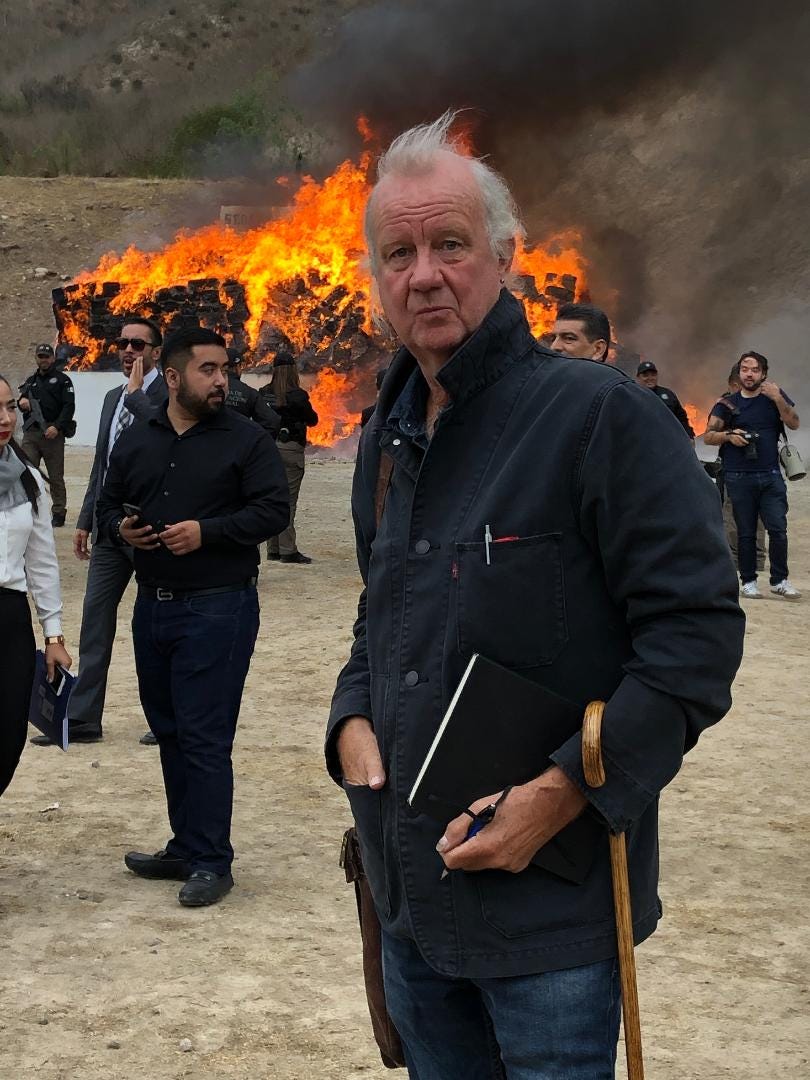

During the early years of the Global War on Terror (2001-2005), I regularly denounced the New American Paradigm on television, radio and in New York Newsday.

I accepted long delays at airports because I “was on a list” and was never surprised to find big, orange Department of Homeland Security cards in my checked bags informing me that their minimum wage mall cops had tossed my dirty clothes. When people called me on my home phone and asked about the loud clicks, and obvious, audible interference, I explained simply that “the government is probably listening,” then added, “Fuck you, Alberto Gonzales.”

I was more afraid of my great‑grandfather and PhD advisor rolling in their graves for my failure to speak the truth than I was of the U.S. government.

That said, after the Iraq invasion, my work became increasingly lonely. People I once counted as allies succumbed to various forms of pressure and got with the New American Paradigm. As a result, I began to distance myself from them and they began to distance themselves from me.

I was fortunate to have a small, but strong, support system. People like criminal defense attorney Andy Patel, laws of war professors Jonathan Bush and Gary Solis, journalists Ed Vulliamy, my editors Peter Dimock and Leslie Kriesel at Columbia University Press, Spencer Rumsey at New York Newsday, and above all, my fearless Southern wife, Annabelle Lee, always strengthened my resolve. There were still others—Senator Jim Webb, Andrew Bacevich, Morris Davis—whom I did not yet know, but whose willingness to speak truth to power, also inspired me and reminded me that I was not alone.

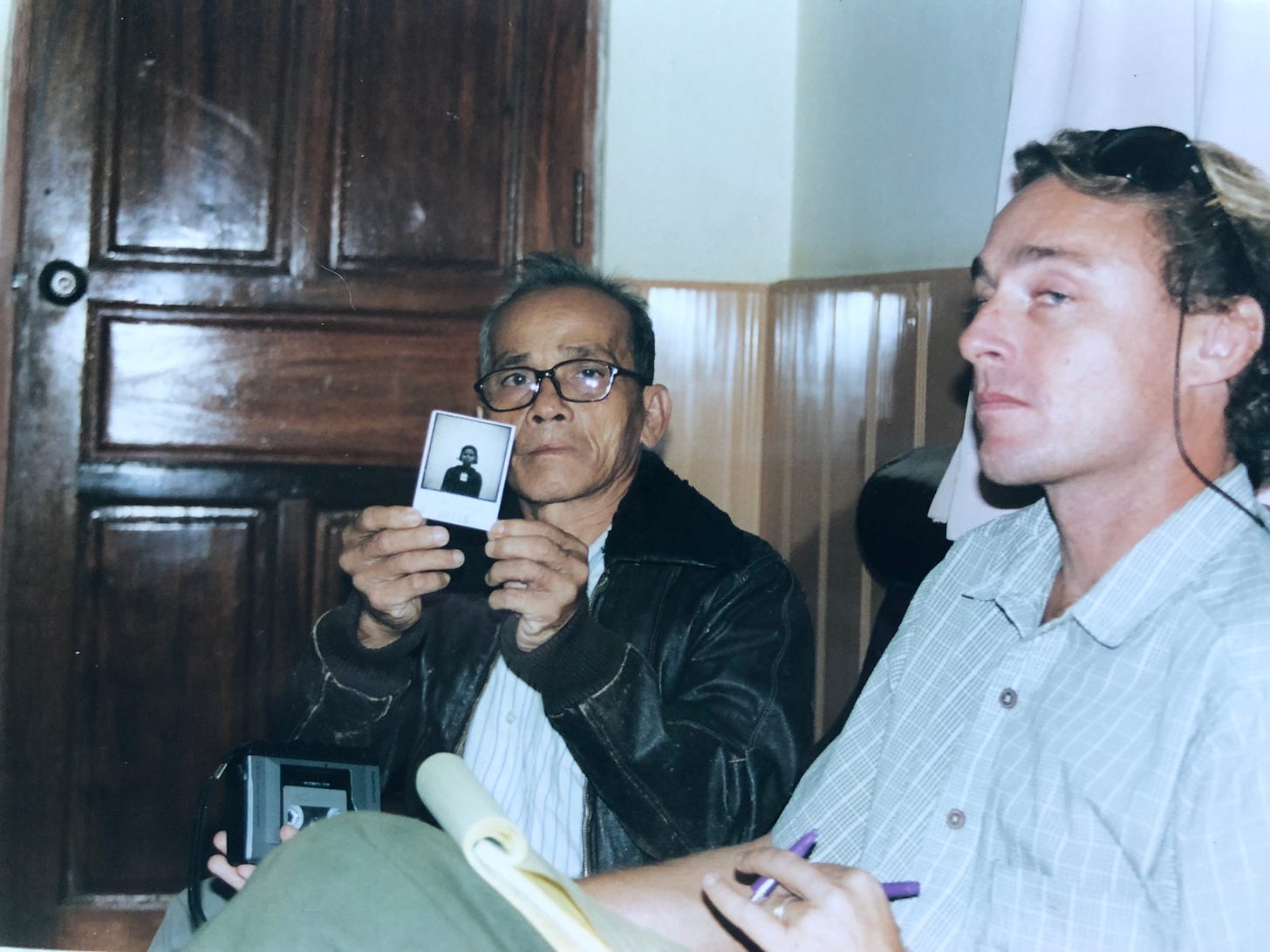

Nobody, however, did more to strengthen my resolve than Rich Arant. Like me, Arant had been very actively involved with the war crimes accountability efforts in Cambodia. Long before the UN swanned onto the scene and held their imperfect and overpriced trials, the accountability efforts were led by the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC CAM). Both Rich and I supported their efforts. While I donated my research to DC CAM, Arant translated many of their articles and books from Khmer into English.

Unlike me, Rich was not a civilian, but a slightly mysterious military professional who had worked in Southeast Asia since the end of the Vietnam War. By 2005, I had spent more than a decade documenting Khmer Rouge atrocities, had interviewed many of the former cadre who had committed them, and knew the inner workings of Security Prison 21 (Tuol Sleng) as well as anyone in the world.

Nevertheless Arant’s short, four-page untitled preface to The Chain of Terror, a 2005 book about Khmer Rouge secret prisons, forced confessions, and executions by Cambodian author Meng-Try Ea, shook me to my core. Arant wrote:

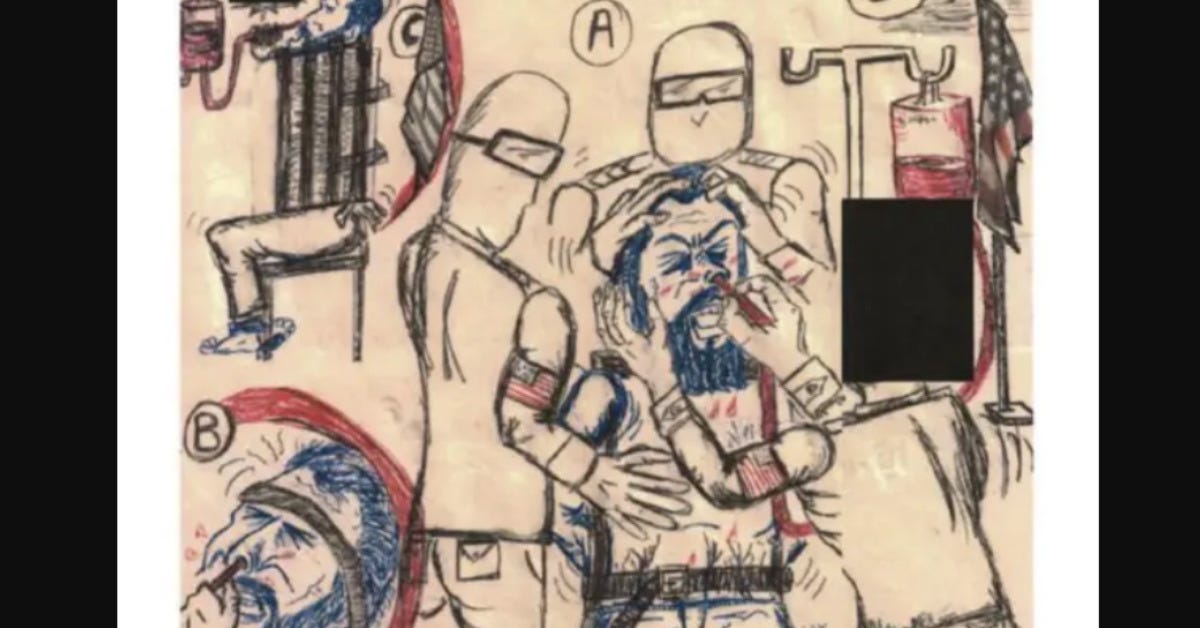

It was during 2002 that I first saw Meng-Try Ea’s draft of The Chain of Terror in the Khmer language. The author asked me to assist him with the English translation. Little did I realize then how much this work would come to haunt me during the next two years.I recall as if it were yesterday sitting at a desk in the Thai Armed Forces Intelligence Operations Center in Bangkok during mid-1975 as a young Army NCO, reading the first Thai intelligence reports of the barbarity that swept Cambodia. My immediate reaction was that the reports were incredible, over the top. My assessment— propaganda.My experience a decade later as an Air Force human intelligence officer interviewing inmates of communist prisons and reeducation camps in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam had, I thought hardened me to the cruelty of prisons and interrogations. More recent memories of interviewing former Khmer Rouge cadre after the United Nations brokered “peace” in Cambodia convinced me I knew what evil these creatures, so unlike us, were capable of carrying out in the name of “The Organization.”Translating The Chain of Terror was a fascinating opportunity to learn more about the evil perpetrated by interrogators and guards inside prisons that operated far beyond the pale of human decency. For months afterwards I would recall at odd times one female witness’s description of the sounds of clubs smashing the skulls of victims kneeling at the edge of freshly dug pits, “the sounds of coconuts falling to the ground.”Then late one night in early 2003 I found myself in the “hard site” at Abu Ghraib, Saddam Hussein’s version of Pol Pot’s S‑21, just a few yards from Saddam’s infamous death chamber, and life changed forever. Standing there in shock, I recalled a phrase from a Khmer Rouge interrogator’s notebook—"When the interrogator is clear in his emotions and principles that the enemy arrested and brought in by the party is a ‘spy,’ the interrogator can successfully carry out his duty. Success is digging up the mysteries hidden by the prisoner and demonstrating to the Party that the prisoner was involved with the enemy.” Upper echelon wanted answers and wanted them now. I soon left, ashamed at being unable to perform my duty. When I sat down my first “terrorist suspect,’” I began with the question, “Why were you arrested?’’” Immediately I thought of the testimony of one of the witnesses in The Chain of Terror: “When I arrived at the interrogation room, the investigator told me to sit down and began asking questions. The first question every time was, “Do you realize why Angkar brought you here?” Seldom does any interrogator really have any reliable information about the prisoner who sits before him. The interrogator must harden his heart sufficiently to act as if he already knows the guilt is there, so he can apply the necessary pressure to convince the prisoner that confession is the only avenue out of a bad situation. Just part of the job, I told myself, [but also remembering the witnesses whose testimony I had translated quoting their interrogators:] “Angkar [The Organization] has never made a mistaken arrest.’”Arant’s Preface continues:

Late one night during November 2004 at the American military prison at Bagram Air base in Afghanistan, I stood in the prisoner-in-processing room and listened to a young MP reading the “house rules” to a just-unblindfolded and still trembling “Taliban suspect.” The MP reads the rules verbatim from a sign posted on the wall behind the prisoner’s back. My mind flashed to the Ten Rules of Santebal [Special Security] written on the blackboard at Pol Pot’s House of Horrors, S-21. Every prison has rules, I assured myself. I watched the stunned expression of newly arrived Afghans and saw the same expressions once registered in the in-processing mug shots taken at S-21. Exploiting “capture shock” is a necessary part of the game. I told myself. Ugly, but unavoidable.As I questioned an Afghan prisoner accused by an unknown paid informant of working against US forces, I went after the identities of anyone he knew who was cooperating with the Taliban, but was distracted by the recollection of Khmer Rouge interrogator Pol telling his prisoner Sen: “Brother if you report the secrets of the party: meaning you betray your party and join with us, we will not be afraid to use you, But Brother, if you do not report, that means you are stubborn and are protecting treasonous forces.”One night in the prison at Bagram I was interrogating an older man, a man my own age, a former Mujahidin cadre who had successfully fought with American support to drive the occupying Soviet Army from his land. A former Afghan communist prison commander, educated and trained by the Soviets, had recently taken a security position with the new free Afghan government and reported to US Forces that my prisoner was cooperating with the radical Taliban mullahs. My prisoner had been “implicated,” to use the Khmer Rouge jargon. My prisoner had once been jailed by the Russians. I began describing how the Khmer Rouge had turned on their own cadres and tortured them to extract phony confessions, this during roughly the same era when the Afghan jihad against the Russians was occurring. I was preparing to make the point that he could trust an American interrogator to treat him with more respect than the Russians had. I was stunned to see this dignified man completely collapse in tears, unable to speak. After my interpreter and I gave him a chance to gather himself, he said, “I fought the Russians, our common enemy, and now you Americans have imprisoned me on the word of a son of the Russians. This is my reward.”Arant continues:

Prisons and interrogations are by their very nature inhumane. Our leaders have taught us that taking a life on today’s battlefield can be a righteous and patriotic act, an act of bravery or self-defense, a “preemptive” necessity in the new age of the war on terror. “Precautionary murder” is the term once used by T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia). Former conventions regarding the treatment of prisoners are now considered quaint, obsolete. But a prisoner is as defenseless as a passenger held hostage on an aircraft. There is little honor found in exploiting his fears, no matter how pressing the requirement. Bringing to light the testimonies of victims of human rights violations, as Meng Try Ea has done so brilliantly here in The Chain of Terror, helps protect us from falling into the trap of imitating the “evil-doing” which we accuse our enemies of initiating.

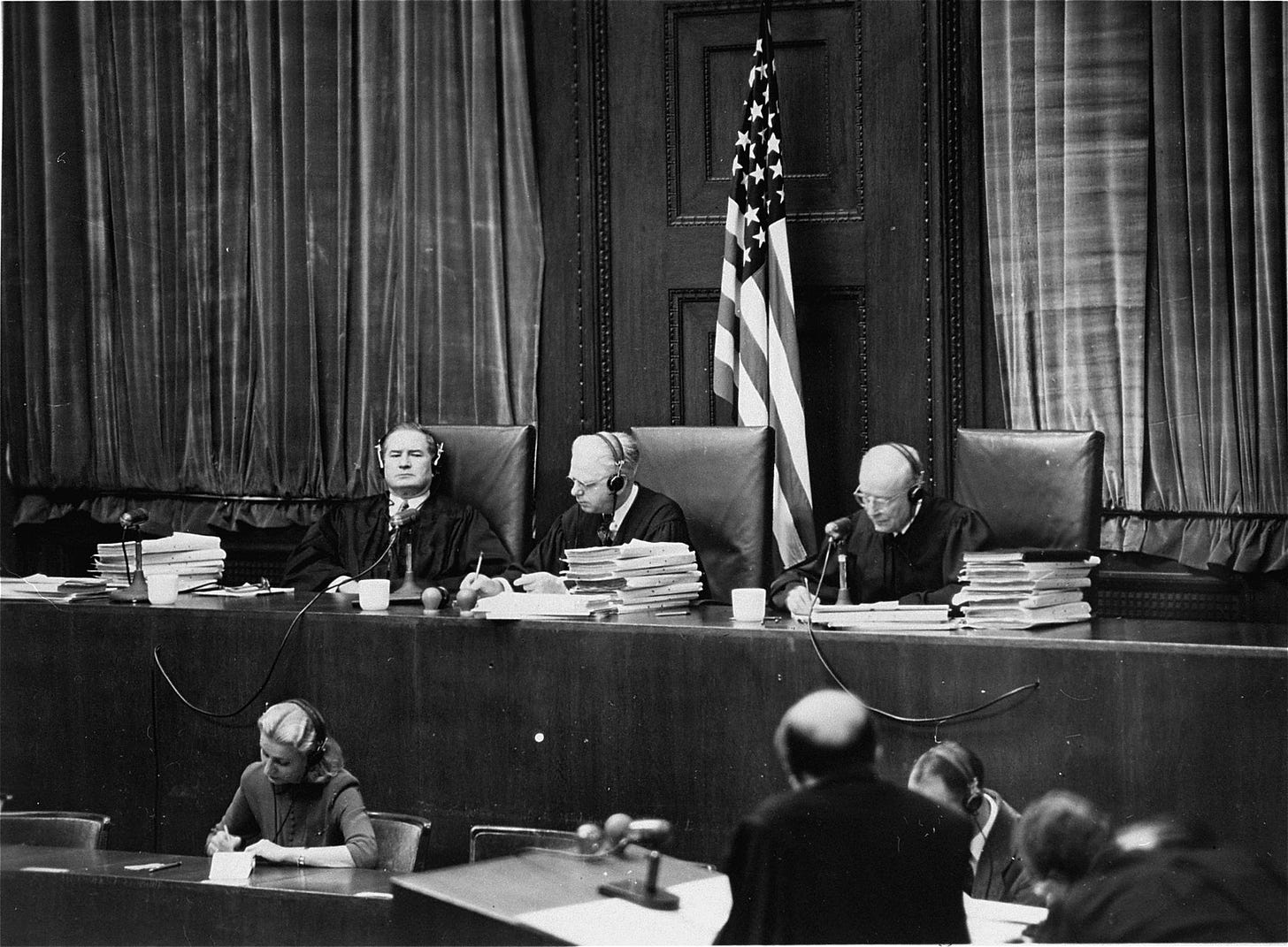

Since 2001, the words of American Nuremberg prosecutor Robert Jackson’s opening address have haunted me. “We must never forget that the record on which we judge these defendants today is the record on which history will judge us tomorrow. To pass these defendants the poison chalice is to put it to our own lips as well.”

After 9/11, Dick Cheney transformed Justice Jackson’s poisoned chalice into a poison keg. Not only did Bush, Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, Rice, Chertoff, Feith, Perle, Gonzales, Ashcroft, Libby, Tenet and Black drink from it like frat boys during rush week, but so did their eager pledges—Yoo, Addington, Hadley, Miller, Rizzo, Sanchez, Bybee, Haynes, Goldsmith, Bellinger, Newstead, Frum, and others. .

Today, more than 23 years, eight trillion dollars, and a million dead later, America has never been more insecure at home and had less power, credibility and moral authority abroad. “The U.S. is no longer the world’s policeman who will enforce the international rules based order,” one dispirited government official wrote me this year after the Biden administration abandoned the 100 million dollar Airbase 201 in Niger. “We’ve instead turned into the fat middle aged crossing guard, standing there in a neon vest, flapping our arms and yelling at the side of the road for cars to slow down.”

I once thought that the U.S.—Dakota War Trials (1862) and the Yamashita case (1945) were the worst stains in American international legal history. However, the Kafkaesque farce that has dragged on for more than twenty years in Cuba, out of sight and mind, at Guantanamo Bay, stands without parallel.

Instead of facing the fact that we have hit rock bottom and ending the two decade-long bender, American leaders have unleashed the New American Paradigm on U.S. citizens who dare question whatever non‑oppositional ideology rules the day.

Because half of the country distrusts the Supreme Court and the other half distrusts the Department of Justice, no matter who wins this bleak election, the U.S. cannot move forward without some form of reckoning. The neoconservatives who created this mess and neoliberals who expanded and presently oversee it need to be held, if nothing else, historically accountable. As for Dick Cheney, although he will never wear headphones in the Hague, there is nothing that can redeem him. If the former Vice President had a sense of shame, he would join George W. Bush at his finger-painting studio in Crawford, Texas and vanish from public sight. Instead, Cheney continues to insert himself into American politics, and it is up to us—democrats, republicans, progressives, libertarians—to shun him like a racist uncle at Thanksgiving dinner.

See my 2009 essay, “The New American Paradigm,” after the Postscript below.

Endnotes for Dick

1. My great-grandfather, Robert Maguire, was a judge at the final American trial at Nuremberg and one of my dissertation advisors, Brigadier General Telford Taylor, was chief prosecutor. Over the past thirty years, I have investigated and documented war crimes, written books (Law and War: Americans History and International Law and Facing Death in Cambodia and articles about the experience, provided pro bono advice to defendants, plaintiffs, governments, and NGOs in war crimes and other high profile trials and investigations like Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia 1997-2015; David Irving v. Deborah Lipstadt/Penguin Books 2000; Donald Rumsfeld v. Jose Padilla 2004; Kiobel v Royal Dutch Petroleum Co. 2012; Investigation and arrest of Yan Yoeun 2021; John Knock Presidential Pardon 2021; Ann Shively and the estate of Michael Jay Shively v. Utah Valley University, Astrid Tuminez, Karen Clemes, and Sara Flood 2022.

2. Nations involved in the New American Paradigm’s kidnapping and torture efforts included: Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Finland, Gambia, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Iceland, Indonesia, Iran, Ireland, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Libya, Lithuania, Macedonia, Malawi, Malaysia, Mauritania, Morocco, Pakistan, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Syria, Thailand, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, Uzbekistan, Yemen, and Zimbabwe.

3. Some of my more prominent stories: “Questions Hang Over Military Tribunals,” New York Newsday, 2001; “Our Standards of Judgment Are Whatever We Wish Them To Be” New York Newsday, 2003; “Bush Can't Have Justice Both Ways,” New York Newsday, 2003; “The Undoing of International Justice,” New York Newsday, 2004; “Here Comes the Judge: Hussein Trial May Set New Low,” New York Newsday, 2004; “Look at Our Prisoner of War Policy Now,” New York Newsday, 2004; “Soldier Serves as Scapegoat in Iraq Scandal While Higher-ups Duck Responsibility,” New York Newsday 2005; “Padilla: US Courts Can Fight Terrorism,” New York Newsday 2007; “UN-Cambodian War Crimes Court Is Tested,” International Herald Tribune, 2009.

POSTSCRIPT:

When I wrote “The New American Paradigm” in 2009, I was working as a defense contractor designing, testing, and building combat rescue boats for the U.S. military.

This work put me in regular contact with the Master Chiefs, Sergeants and Captains who were actually fighting these wars. These young men had not just spent the best years of their life far from home, they had lost friends, been touched by fire, and had lost faith in their political leaders.

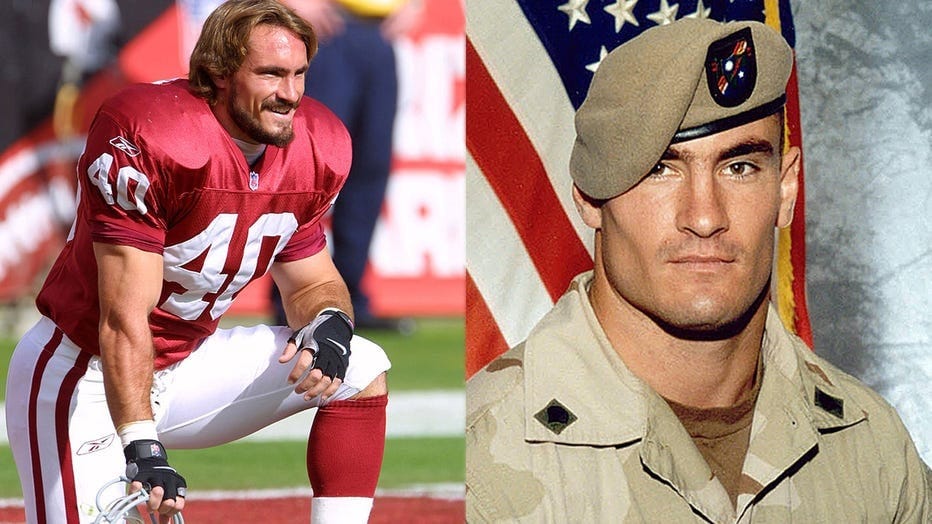

I wrote “The New American Paradigm” for them and the others, like Pat Tillman, who did not make it home. To me, Tillman was a sad metaphor for the War on Terror. The NFL star walked away from a lucrative gridiron career only to be killed by friendly fire. After the Bush administration’s attempt to cover up the cause of his death, Tillman’s mother, Mary, testified, "The deception surrounding this case was an insult to the family, but more importantly, its primary purpose was to deceive a whole nation."

“The New American Paradigm”

(This essay was first published in 2009 as a postscript for my book Law and War: American History and International Law).

Today, the Nuremberg trials and the principles that they spawned seem like quaint memories from a long-bygone era. The 9/11 attacks and the ensuing “Global War on Terror,” forced America’s international legal duality out into the open for all to see. Weeks after 9/11, senior Justice Department lawyers convinced President Bush that the “War on Terror” was a new kind of war requiring “a new paradigm” that would render the Geneva Convention’s strict limitations on the treatment of enemy prisoners “obsolete.”1Unlike previous American presidents who claimed to support inter- national law when the outcome was favorable to the United States, President Bush explicitly rejected both long-standing, codified laws of war like the Geneva Conventions and older customary distinctions such as that be- tween soldier and civilian.2 The Bush administration pushed aside the military professionals and argued that there were no limits—constitutional or congressional — on presidential authority.3Brazen disregard for the laws of war was soon elevated to a matter of principle as America began a sordid affair with what Vice President Cheney described as “the dark slide.” Even though the U.S. Second Court of Appeals compared torturers to slave traders in a 1980 opinion, by the summer of 2002 the United States had redefined torture to include only those acts that resulted in death or organ failure. According to the new American definition, not even John McCain’s treatment at the hands of the North Vietnamese met the new standard.4President Bush officially declared war on international criminal law when he unsigned the Rome Statute establishing the International Criminal Court in July 2002. Conservatives viewed the ICC and the concept of “uni- versal jurisdiction” as a kind of inverse strategic legalism or “lawfare.” Ac- cording to Brigadier General Charles Dunlap, lawfare used the law instead of military force “to achieve an operational objective.”A new federal law called the American Service-Members’ Protection Act (better known as the Hague Invasion Act), passed in August 2002, authorized the President to use “all means necessary and appropriate to release US prisoners of the ICC.” The Bush administration also began suspending aid to countries that refused to give U.S. citizens immunity before the ICC. Initially the Bush administration took the position that neither the federal War Crimes Act nor the Geneva Conventions constrained U.S. forces in Afghanistan. Because the United States deemed that nation “a failed state,” they could define both Al Qaeda and the Taliban as “illegal enemy combatants” unprotected by common Article 3 of the Geneva Convention.5It was one thing for American Special Forces teams to play fast and loose with the laws of war on hot battlefields in the Pashtu frontier, where the ir- regular nature of the foe merited such an approach. However, by the time the war shifted to Iraq, “torture’s perverse pathology” had taken root, and now army reservists were applying similar standards during the invasion of a sovereign nation. According to historian Alfred McCoy, not only does torture fail to provide reliable intelligence, it also “leads to both the uncontrolled proliferation of the practice and long-term damage to the perpetrator society.”6Although the term “enemy combatant” was used as a strategic legal mechanism to get around international humanitarian law, when all else failed, the Bush administration invoked simple messianic unilateralism. “Good” and “Evil” became the new “metrics” for a vague new American foreign policy whose exponents claimed to be on a crusade to rid the world of “Evil” and to spread “Freedom.”7 Very suddenly, colonialism, crusades, nuclear weapons, and prayer breakfasts were all the rage for ambitious post–9/11 D.C. Republicans. Not only did America’s evangelical President describe the War on Terror as a “Crusade,” he claimed “God” had told him to strike at Al Qaeda and Saddam Hussein.8 However, this Judeo-Christian inspired, reflexively anti-Islam rhetoric and policy proved strategically unsound and worked as a force multiplier for America’s enemies. Soon the United States was fighting not only Al Qaeda but also “Islamofascism” and “IslamHitlerites.”9After 9/11, human rights utopians were immediately replaced by proud neo-imperialists who called for a unipolar world, with America striking out preemptively against threats both real and imagined. Russian-born Wall Street Journal editor, Council on Foreign Relations fellow, and L.A. Times columnist Max Boot argued that “Afghanistan and other troubled lands to- day cry out for the sort of enlightened foreign administration once pro- vided by self-confident Englishmen in jodhpurs and pith helmets.” Heav- ily praised by the mainstream press, Boot’s 2002 book, Savage Wars for Peace, points to the 1898 U.S. war in the Philippines as a template for the “War on Terror.” “In deploying American power, decision makers should be less apologetic, less hesitant, less humble,” wrote Boot. “America should not be afraid to fight ‘the savage wars of peace’ if necessary to enlarge the ‘empire of liberty. ’”10 President Bush’s Canadian speechwriter, David Frumm, and Iraq War architect, Richard Perle, went so far as to claim that the stakes for the United States in the War on Terror were “victory or holocaust.”11The War on Terror’s cheerleaders and enablers were not limited to the right. Pro-war columns by liberal hawks like Judith Miller, Michael Gordon, Thomas Friedman, Michael Ignatieff, David Remnick, Jeffrey Gold- berg, Peter Beinart, Paul Berman, and Kenneth Pollack helped to sell and justify U.S. policy and conduct. “The press played ball. After 9/11, they rolled over and played dead,” said the dean of the White House press correspondents, Helen Thomas. “Really, they asked no questions, they all had to be patriotic. . . . To ask a question was to be unpatriotic, un-American and so forth.”12 Even the onetime human rights advocates at Harvard’s Carr Center blew with the wind. Not only did Michael Ignatieff advocate the use of torture, his colleague Sara Sewall advised the U.S. military on counter- insurgency policy, and even Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Samantha Power, who was quick to point out atrocities in Darfur, remained conspicuously silent about the new American paradigm.13 It is no coincidence that today all three are politicians or policy makers.The most incisive criticism of the Bush administration’s POW policies came from professional soldiers who were growing increasingly uncomfortable with multiple combat tours ordered by civilian leaders who had never been in a fistfight, much less a firefight. Because the career military lawyers supported Geneva Convention protections for prisoners, they were simply cut out of the policy-planning process.14 One heavily decorated Vietnam war veteran wrote: “Never before in our country’s history has an administration charged with defending our nation been so lacking in hands-on combat experience and therefore so ignorant about the art and science of war.”15 Secretary of State Colin Powell, one of the few Vietnam veterans in the Bush administration, argued forcefully and prophetically that the new American paradigm would “reverse over a century of U.S. policy and practice,” and predicted “a high cost in terms of negative international reaction, with immediate adverse consequences for our conduct of foreign policy.”16Many American policy makers, pundits, and academics attempted to rationalize the use of torture based largely on the “ticking time bomb” scenarios of television supersleuth Jack Bauer. There was, however, one problem: torture does not provide a steady stream of reliable intelligence, as evidenced by testimony of superterrorist Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. After months of torture and isolation, “KSM” confessed to masterminding thirty Al Qaeda operations and even wielding the knife that decapitated Daniel Pearl.17“We are falling into the trap of imitating the ‘evil-doing’ which we accuse our enemies of initiating,” wrote Rich Arant. A contract interrogator who worked at Abu Ghraib and Afghanistan’s Bagram Air Force base in 2003–4, Arant had a revelation one night while questioning a former Afghan Mujahid who had fought against the Soviets and was now in jail be- cause a paid U.S. government informant and well-known Soviet collaborator had fingered him. When Arant told the old soldier he could trust an American to treat him with more respect than the Russians, “this dignified man completely collapsed in tears, unable to speak,” wrote Arant. “After my interpreter and I gave him a chance to gather himself, he said, ‘I fought Russians, our common enemy, and now you Americans have imprisoned me on the word of a son of the Russians. This is my reward.’” Arant quit shortly thereafter and offered this observation:‘Our leaders have taught us that taking a life on today’s battlefield can be a righteous and patriotic act, an act of bravery or self-defense, a “preemptive” necessity in the new age of the war on terror. “Precautionary murder” is the term once used by T. E. Lawrence, Lawrence of Arabia. Former conventions regarding the treatment of prisoners are now considered quaint, obsolete. But a prisoner is as defenseless as a passenger held hostage on an aircraft.’There is little honor found in exploiting his fears, no matter how pressing the requirement.”By the time the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, extraordinary rendition, secret prisons, indefinite detention of American citizens, domestic espionage, and watch lists were all accepted as facts of life by a stunned and submissive American population who viewed the havoc wrought in their name from afar. That arm’s-length relationship was shattered in 2004 when General Anthony Taguba’s report on prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib was leaked to Seymor Hersh and photographs of American soldiers perversely torturing and humiliating common Iraqi criminals flashed around the world in seconds. Bin Laden himself could not have staged a more successful propaganda coup as smiling, fresh-faced American girls led naked Iraqi men on leashes. One senior policy maker described the perpetrators to me as “the seven soldiers who lost the war.”19The Bush administration’s response to the Abu Ghraib affair was similar to President Theodore Roosevelt’s response to atrocities in the Philippines War or President Nixon’s response to the Mai Lai Massacre: the perpetrators were “a few bad apples” and these were “isolated” events.20However, this buffoonery was limited to the Abu Ghraib Seven. This appendix from the Taguba Report speaks for itself: in a sworn statement, a U.S. soldier stationed at Abu Ghraib wrote, “I climbed a yellow ladder . . . to see a light skinned, black male . . . taunt the prisoners by flexing and shouting at them. Right after this, a Caucasian soldier . . . taunted the prisoners of compound ‘B’ and ‘C’ by similar means of flexing and shouting at them. This caused the prisoners to become extremely irate, and a short riot ensued that resulted in gunfire” (seven Iraqis were shot).21It did not take long for American POW policy to be denounced by our British allies, the U.S. Supreme Court, federal judges, the International Red Cross, and the American Bar Association. Now there is irrefutable documentary evidence that even American doctors and psychiatrists violate the Geneva Conventions, the Nuremberg medical standards, and the Hippocratic oath. The New England Journal of Medicine called the complicity in the interrogation process “a matter of national shame.”22 Military professionals, like former Navy Judge Advocate General, Rear Admiral John Hutson, rejected the few bad apples argument: due to “the range of individuals and locations involved in these reports, it is simply no longer possible to view these allegations as a few instances of an isolated prison.”23The Guantanamo Bay camp is in many ways a distraction, a set piece, or as defense attorney Clive Stafford Smith put it, a “lightning rod not only for criticism but also for global attention.” Largely ignored is the archipelago of secret prisons around the world where “high-value” detainees are tortured, interrogated, and sometimes killed. FBI agents who visited the Cuban prison were shocked by both the style and the substance of the interrogations. Stupidly brutal, proudly racist, and deeply perverse, the FBI agents witnessed scantily clad female interrogators sexually taunting Muslim captives (one even smeared fake menstrual blood on a suspect).24 FBI agents watched one “detainee sitting on the floor of the interview room with an Israeli flag draped around him, loud music being played and a strobe light flashing.” According to one FBI memo, the theatrics “produced no intelligence.”25When it came to war crimes trials for the vanquished, the Bush administration employed traditional, primitive political justice. As a result, it could not even provide an easily convicted thug like Saddam Hussein with a de- cent show trial. The fallen Iraqi leader’s chaotic American-choreographed proceeding saw lawyers murdered, courtroom brawls between defendants and guards, and even an execution video on YouTube before it made the morning papers.26 The treatment meted out to American and Australian collaborators like Jose Padilla, John Walker Lindh, and David Hicks has been oddly unsystematic, as if the prosecutors were making up the rules as they went along.The self-contained legal bubble of Guantanamo Bay has become a sort of Orwellian version of Alice’s Wonderland where even defendants found not guilty “can be held in perpetuity.”27 The Gitmo military commission was firmly under the control of Vice President Dick Cheney and his political appointee Susan Crawford. Navy Lieutenant Commander Brian Mizer filed a motion in 2008 that charged senior Pentagon appointees with “exercising unlawful command influence” by pressuring prosecutors to charge “high- value” detainees in order to gain “strategic political value” before the 2008 election.28 The tribunal’s top legal official, Brigadier General Thomas Hart- man, was removed from his position after judges in three separate cases barred him from participating in trials due to his pro-prosecution bias.29 Convinced that political interference made fair trials impossible, Colonel Morris Davis, Major Robert Preston, Captain John Carr, and Captain Carrie Wolf all resigned.Australian David Hicks was the beneficiary of an eleventh-hour political deal that sent the prisoner home in a futile effort to aid Australian Prime Minister John Howard’s doomed reelection effort. Although Hicks signed a document claiming that he had not been mistreated by Americans, this statement was contradicted by his earlier affadavit.30 “The charade that took place at Guantanamo Bay would have done Stalin’s show trials proud,” said one of Australia’s most experienced criminal lawyers, Robert Richter. “First there was the indefinite detention without charge. Then there was the torture, however the Bush lawyers, including the attorney general, might choose to describe it. Then there was the extorted confession of guilt.”31The Bush administration strained to make an analogy between the Nuremberg and Gitmo trials. In the lead-in to the first Gitmo trial, U.S. diplomats received a memo that instructed them to point to the execution of Nuremberg convicts to justify the death penalty at Guantanamo Bay.32 Brigadier General Hartmann went so far as to claim that the legal protections for Guantanamo Bay defendants “exceed those that were available at Nuremberg.”33 Colonel Morris Davis described one conversation with the Pentagon’s top lawyer and recently resigned torture advocate, William Haynes, who tried to describe the Gitmo trials as “the Nuremberg of our time.” When Davis reminded him that defendants at Nuremberg were ac- quitted, Haynes appeared shocked and replied: “Wait a minute, we can’t have acquittals. If we’ve been holding these guys for so long, how can we explain letting them get off? We can’t have acquittals, we’ve got to have convictions.”Although the Bush administration and Guantanamo officials continue to compare the Guantanamo Bay military commission to the Nuremberg trials, nothing could be further from the truth. It took Nuremberg’s international court less than 13 months to indict, try, and sentence Nazi Germany’s top leaders in an imperfect but highly credible procedure. Between late 1946 and 1949, the United States tried another 177 German leaders in 12 more trials at Nuremberg.34 At no point did the United States monitor the work of the defense attorneys or authorize the use of torture to gain information. No Nuremberg defendants or their lawyers ever alleged that they were tortured. Former Nuremberg prosecutor Henry King found the analogies offensive: “To torture people and then you can bring evidence you obtained into court? Hearsay evidence is allowed? Some evidence is available to the prosecution and not to the defendants?”35The Guantanamo Bay tribunals would have lived up to the worst star chamber expectations were it not for the verdict in the Hamdan case. In a split decision, a six-officer military commission convicted Osama Bin Laden’s driver, Salim Hamdan, of the lesser charge of providing material support for terrorism, but acquitted him of the more serious conspiracy charge. The Hamdan case proved once again that even primitive political justice cannot be stage-managed.36Thankfully, not all Americans have given in to the fear. U.S. District Judge John Coughenour tried and convicted Algerian Ahmed Ressam for his plot to bomb Los Angeles Airport. Coughenour did not need a secret military tribunal, or indefinite detention, or to deny the defendant the right to counsel, or to deem him “an enemy combatant.” The judge explained, “The message to the world from today’s sentencing is that our courts have not abandoned our commitment to the ideals that set our nations apart.” According to Coughenour, if the prevailing American view becomes that terrorism renders the Constitution obsolete, “the terrorists will have won.”37Former Navy General Counsel Alberto Mora was another who pushed back against the Bush administration: “When you put together the pieces, it’s all so sad. To preserve flexibility, they were willing to throw away our values.”38 With the establishment of a new, Democratic administration and a fresh set of international crises causing near-seismic shifts, Americans would be wise to consider the words of American Nuremberg prosecutor Robert Jackson’s now famous opening address: “We must never forget that the record on which we judge these defendants today is the record on which history will judge us tomorrow. To pass these defendants the poison chalice is to put it to our own lips as well.”39End Notes for “The New American Paradigm”

1. Testimony of Cofer Black to the Joint Congressional Intelligence Committee, September 26, 2002; http://www.fas.org/irp/congress/2002_hr/092602black.html.

2. Jameel Jaffer and Amrit Singh, Administration of Torture (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), A1–5. “But under this New Paradigm, the President gave terror suspects neither the rights of criminal defendants nor the rights of prisoners of war,” wrote Jane Mayer in her groundbreaking book, The Dark Side: The Inside Story of How the War on Terror Turned Into a War on American Ideals (New York: Doubleday, 2008), 51–52.

3. Bush also announced that the United States could use military force preemptively against terrorist organizations or the states that harbor or support them. Mayer, The Dark Side, 64–65. According to one of John Yoo’s 2001 memos, “These deci- sions, under our Constitution, are for the President alone to make.”

4. Alfred McCoy, A Question of Torture (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2006). “War means killing people,” the architect of the new American paradigm, John Yoo, explained in a 2007 interview. “If we are entitled to kill people, we must be entitled to injure them.”

5. Jaffer and Singh, Administration of Torture, A1–5.

6. McCoy, A Question of Torture, 112; Scott Shane, “Soviet-Style ‘Torture’ Becomes ‘Interrogation,’” The New York Times, June 3, 2007. “When you say something down the chain of command like, ‘The Geneva Conventions don’t apply,’ that sets the stage for the kind of chaos we have seen,” said retired Judge Advocate General Rear Admiral John Hutson.

7. Mayer, The Dark Side, 240 – 41.

8. Deputy Secretary for Defense Intelligence, Lieutenant William Boykin called the War on Terror a “holy war against Satan.” According to Boykin, “Our spiritual enemy will only be defeated if we come against them in the name of Jesus.” Richard Leiby, “Christian Soldier,” Washington Post, November 6, 2003.

9. “Was the USA unleashing pent-up rage, seeking vengeance for every military engagement it had lost or terrorist act that it had suffered?” asked former Guantanamo Bay prisoner Mossam Begg. “Well, almost. The common denominator was Islam.” David Horowitz, “Jimmy Carter: Jew-Hater, Genocide-Enabler, Liar,” Front Page Magazine, December 14, 2006; Moazzam Begg and Victoria Brittain, Enemy Combatant: My Imprisonment at Guantanamo Bay, Bagram, and Kandahar (New York: New Press, 2007), 111.

10. Max Boot, The Savage Wars of Peace (New York: Basic Books, 2002), 352.

11. David Frumm and Richard Perle, An End to Evil (New York: Random House, 2003), 9. Disney/ABC radio host Paul Harvey did his best to stiffen the American spine and in the process demonstrated the insidious effects of “torture’s perverse pathology” in one 2005 radio address: “we didn’t come this far because we’re made of sugar candy. Once upon a time, we elbowed our way onto and into this continent by giving smallpox-infected blankets to Native Americans. Yes, that was biological warfare! And we used every other weapon we could get our hands on to grab this land from whomever. And we grew prosperous. And, yes, we greased the skids with the sweat of slaves” (Paul Harvey Show, ABC Radio, June 23, 2005). According to a Gallup poll, by 2005, more than one in four Americans approved of the use of nuclear weapons in the War on Terror. Another survey found that a majority of American high school students believed that newspapers “should not be allowed to publish without government approval,” and even more shocking, one in five said that “Americans should be prohibited from expressing unpopular opinions.”

12. Helen Thomas, Media Matters interview, May 12, 2006; http://vodpod.com/ watch /97344-helen-thomas-on-the-medias-failure.

13. Ron Steel blasted Ignatieff in a New York Times review of Ignatieff ’s book The Lesser Evil: “In concocting a formula for a little evil lite to combat the true evildoers, Mi- chael Ignatieff has not provided, as his subtitle states, a code of ‘political ethics in an age of terror’ but rather an elegantly packaged manual of national self-justification.” Alfred McCoy was also extremely critical of Ignatieff. He described the American press and public’s “willful blindness” and “studied avoidance” of American con- duct in the War on Terror. The human rights advocate turned Canadian politician did a one-eighty after the Abu Ghraib debacle and subsequently wrote an embarrassingly feeble mea culpa in which he blamed his lapse of judgment on too many years as a hothouse academic at Harvard. “The Lesser Evil,” The New York Times, July 25, 2004.

14. McCoy, A Question of Torture, 128. Major General Jack Rives, Air Force Judge Advocate General, argued that the more extreme interrogation techniques not only put “the interrogators and chain of command at risk of criminal accusations abroad,” they also damaged the military’s “culture and self image.”

15. David Hackworth, “Fry the big fish, too,” February 1, 2005, www.worldnetdaily .com.

16. Colin Powell, Memo to the Counsel to the President, January 26, 2002.

17. Robert Baer, “Why KSM’s Confession Rings False,” Time, March 15, 2007; Katherine Shrader, “Officials: Mohammed Exaggerated Claims,” AP, March 15, 2007; Josh Meyer, “Detainee Says He Confessed to Stop Torture,” Los Angeles Times, March 31, 2007.

18. Meng Try Ea, The Chain of Terror (Phnom Penh: The Documentation Center of Cambodia, 2002), 2: “Upper echelon wanted answers, and wanted them now. I soon left, ashamed at being unable to perform my duty.”

19. News.findlaw.com/hdocs/docs/iraq/tagubarpt.html.

20. Robert Jervis, The Logic of Impressions in International Relations (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989). “Unlike Nuremberg, which led with the trials of the top leadership of the Third Reich and only gradually worked its way down to the bottom of that evil ladder,” wrote Col. David Hackworth, “our leaders are, so far, successfully ducking any responsibility for the crimes perpetrated on their watch.”

21. Sworn statement taken at Baghdad Airport Confinement Facility, June 6, 2003. Another U.S. soldier wrote in a sworn statement: “X choked him until he passed out X stated that X was beating him because Y is a Muslim and X is a Christian.”

22. Jane Mayer, “The Experiment,” The New Yorker, July 11 and 18, 2005.

23. Hackworth, “Fry the big fish, too,” https://www.wnd.com/2005/02/28723/.

24. www.cbsnews.com / htdocs /pdf / FBI_gitmo_detainees.pdf.

25. Ibid.

26. James Rosen, “Saddam Trial at Uncertain Juncture,” McClatchy Newspapers, February 13, 2006.

27. “Annan Backs UN Guantanamo Demand,” BBC, February 17, 2006; “Guantanamo Inmates Can Be Held in Perpetuity,” Reuters, June 15, 2005; “I think if you combine excessive arrogance and excessive ignorance, you wind up 78 months later where we are in this process,” said former Gitmo prosecutor Colonel Morris Davis, who resigned in protest. Josh White, “Prosecutor Alleges, Pentagon Played Politics,” Washington Post, October 20, 2007.

28. White, “Prosecutor Alleges, Pentagon Played Politics”; Carol Williams, “Defender Says Advisor Exerts Illegal Sway,” Los Angeles Times, March 28, 2008; William Glaberson, “An Unlikely antagonist in the Detainees’ Corner,” New York Times, June 19, 2008.

29. “Guantanamo Bay Prosecutor Steps Down,” BBC, September 25, 2008; Mike Melia, “Former Gitmo Prosecutor Blasts Tribunals,” AP, September 26, 2008; Deputy Prison Camp Commander Brigadier General Gregory Zanetti called Hartmann’s conduct “abusive, bullying, and unprofessional.” Lieutenant Colonel Darrel Vandeveld resigned rather than prosecute a case against an Afghan teenager accused of throwing a grenade at U.S. soldiers. Vandeveld said that he could no lon- ger serve due to the “slipshod” evidentiary procedures.

30. Carol Williams, “Detainee’s Plea Deal Angers Some Legal Experts,” Los Angeles Times, April 1, 2007; “Hicks Case Points up Problems Facing US ‘Terror’ Tribunals,” AFP, April 1, 2007; “Guantanamo Follies,” The New York Times, editorial, April 6, 2007.

31. “Trial Would Have Done Stalin Proud—Lawyer,” Sydney Morning Herald, April 1, 2007.

32. “U.S. Diplomats to Use Nuremberg Defense,” The Australian, February 14, 2008; Matthew Lee, “U.S Likens Death Penalty War Court to Nuremberg,” AP, February 12, 2008.

33. Dan Ephron, “Fair, Open, Just, Honest: A Chat with the Adviser to the Gitmo Mil- itary Commissions,” Newsweek, June 2, 2008.

34. Frank M. Buscher, The U.S. War Crimes Program in Germany, 1946–1955 (West- port, Conn.: Greenwood, 1989), appendix A.

35. Martha Neil, “Nuremberg Attorney: Gitmo Trials Unfair,” ABA Journal, June 11, 2007. To King, the United States “has always stood for fairness. We were the ones who started war crimes tribunals and we’re the architects. I don’t think we should turn our back on that architecture.”

36. www.hamdanvrumsfeld.com /.

37. Hal Bernton and Sara Jean Green, “Ressam Judge Decries U.S. Tactics,” The Seattle Times, July 28, 2005.

38. Mayer, The Dark Side, 228.

33. http://www.roberthjackson.org/Man/theman2–7-8–1/.