John Milius

Child of the Bomb

I was 13 when Big Wednesday opened in 1978. I went to see it with a friend I’d been surfing with at State Beach since grade school. We were among the first to buy tickets. For more than a year, we’d been anticipating West LA surfer and Hollywood enfant terrible John Milius’ surfing epic about coming of age at Malibu in the early ’60s.

Two hours after we walked into the National Theatre in Westwood, we walked out inspired to carry on Jack, Matt, and Leroy’s legacy. Our sentiment, however, was not shared by my mother’s boyfriend, the installation artist Robert Irwin. Never one to hold his tongue when it came to matters of art and culture, Irwin—an LA native and former lifeguard—cut our teenaged reverie short. “The only good scene in that movie was the bar fight in Mexico,” he said. “That Mickey Mouse macho surfer bullshit won’t get you very far in Tijuana.”

Irwin was not alone. Film critics were waiting with sharpened beaks for Big Wednesday, and it quickly turned into a pecking party. “The surprise is not that Mr. Milius has made such a resoundingly awful film, but rather that he’s made a bland one,” wrote Janet Maslin in The New York Times. Variety piled on: “A rubber stamp wouldn’t do for John Milius,” reported the publication’s staff review. “So he took a sledgehammer and pounded ‘Important’ all over Big Wednesday.” Not to be outdone, critic, author, and American historian Gary Jack Willis wrote, “John Milius tries to make the spurious sport of surfing into some monumental rite of passage.”

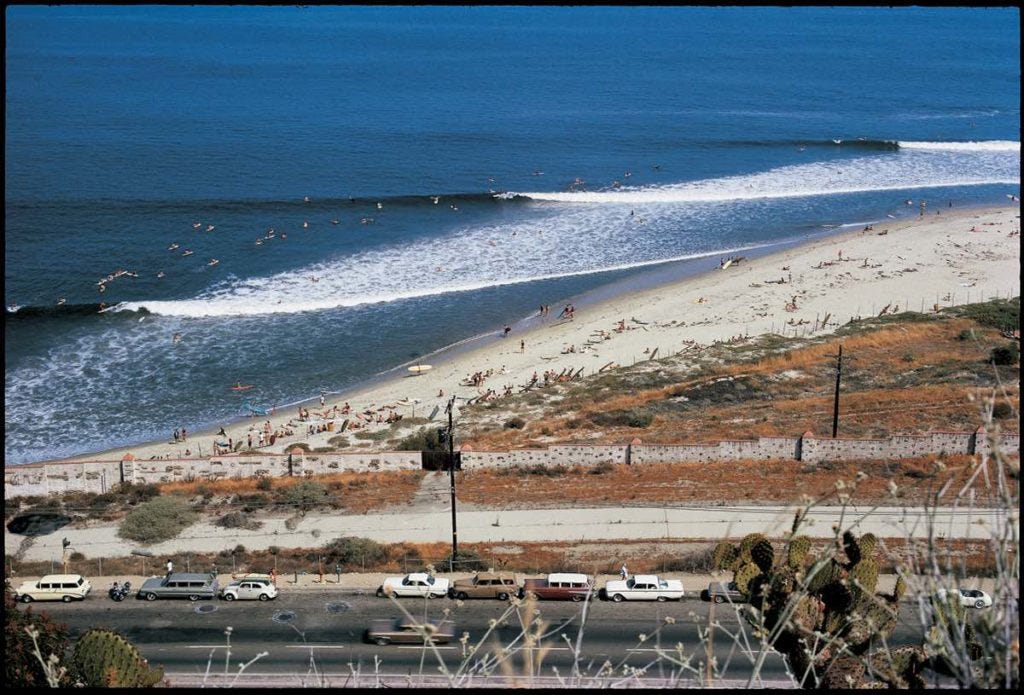

It’s a good thing that we rushed to see Big Wednesday. Weeks after opening, it was pulled from theaters. I, however, was oblivious to the criticism. The film had affirmed what I already knew: Surfers were an elite group that I was lucky to be part of. That summer, I arranged rides to Malibu with anyone who’d take me. While the names had changed since Milius and his friends surfed the point, the characters remained the same. Even in 1978, Malibu during a big summertime south swell was still a Greek play.

That summer, I lurked between Second and Third Point on my trusty 5'11" Natural Progression diamondtail, catching whatever scraps I could. I watched Allen Sarlo smash the most vertical off-the-tops I’d ever seen and Jay “The Riddler” Riddle thread tubes in statuesque cheater fives.

Also prominent in my teenage eyes were the stylists: lifeguard John Baker and hairdresser Steve Dunn. The brawlers: Dave White, Johnny Gyro, and Angie Reno. The fun-loving rippers: Mike “Muzzy” Marcellino and his wingman, Kirk Murray.

And the hot Colony kids: Ian Warner, the Lyon brothers, and Matt Rapf.

It wasn’t all bread and circuses that first summer. I also learned stern lessons. “Stay out of the way, you fucking kook!” screamed a red-faced man, inches from my face. Never again would anyone have to tell me not to paddle for the shoulder. Between sessions, I devoured greasy Jack-in- the-Box tacos and eavesdropped on the beachside chorus that shared joints and judgment on every wave of every set. The conflicts in the water that sometimes spilled onto the sand were exciting because the stakes were so high. Reputations were won and lost in seconds.

Between sets, I watched bonobo-like mating rituals between beautiful beach sirens as they competed for the fragmented attention of the surfers.

Most importantly, I surprised myself that summer by catching the odd set wave that slipped through the crowd, and my surfing improved exponentially. Like John Milius, Malibu became an important strand in my DNA. Many years later, I would realize the reason Big Wednesday spoke so loudly to me: It wasn’t just about the formative period of Milius’ youth. It was about the formative period of my youth. We were members of the same tribe.

John Milius was born in 1944 to a prosperous and cultured St. Louis family. From his earliest memories, narrative, both written and oral, shaped his life. “My father would read or tell me stories,” Milius says in the book Big Bad John, a collection of interviews by the writer and film critic Nat Segaloff, which amasses nearly 50 years of the author’s conversations with Milius. “I remember he read James Fenimore Cooper to me [The Last of the Mohicans]. But one of the very first stories that he ever read to me, which told me something about him, was The Rough Riders,” Theodore Roosevelt’s account of the First US Volunteer Cavalry, the regiment he led during the Spanish-American War.

After Milius’ father retired from a successful career in the shoe business, he decided that California was where he wanted to raise his three children, and the family moved to Bel Air in 1951. Two years too old to officially be counted as a baby boomer, Milius would later describe himself as a member of “the bomb generation” and believed that the Cold War had defined him: “We lived every waking moment under the threat of nuclear annihilation. Mutually assured destruction. We got used to it: drop drills, sirens, the Red Menace.”

By 12, Milius was a volunteer in the Air Force Ground Observer Corps and spending weekends in an observation tower in the Santa Monica Mountains, scanning the horizon for “Badgers” (Soviet Tupolev Tu-16 bombers) coming in fast and low from the northwest. As fascinated as he was with flight, aviation took a back seat when he began to surf that same year. Like most West LA surfers, Milius got his start at State Beach and migrated north as he improved.

One day at Sunset Boulevard, the mushy right where Sunset meets PCH, Beverly Hills surfers Joel Bass and Jack Barth had their “first encounter” with Milius, who was wearing a fur-collared parka over a pair of wet swim trunks. “Joel found him in a crevasse along the cliff, coming out of a cave like a bear,” Barth told me. Bass—the only one of the three with a driver’s license—drove Milius home to Bellagio Road afterward, and the trio became fast friends. Soon they were surfing State, the Jetty, Topanga, Malibu, and Secos together.

Milius rode a balsa wood Velzy-Jacobs and was surprisingly agile for his size. “He wasn’t flashy. He was more elegant,” Barth said. “The aesthetic sensibility at that moment amongst us was to try to be elegant. Smooth, I guess, would be the word.” When they surfed the State Beach jetty, Milius would call himself the “Yeti at the Jetty.” “He’d act it out,” said Barth. “Everything, John acted out. My youth was one big hysterical laugh because of him.”

To Milius, “Malibu was Mecca” and West LA surfers Miki Dora and Lance Carson were “the best in the world.”

The Pit—where the elite surfers, their courtiers, and the court jesters hung out—was just as attractive and fascinating as the perfect waves. “You’d see the rise and fall of great men, empires built and lost, and all of this was done within the Pit,” he said in Milius, a 2013 documentary directed by Joey Figueroa and Zak Knutson.

Milius was known at Malibu as “Viking Man” and called his 9'6" Jacobs “Odin’s Arrow.” He was on his way to becoming a standout surfer, but he was also becoming the black sheep of his family. Like many surfers during the post–World War II era, he was what historian James Gilbert described in his book on 1950s juvenile delinquency, A Cycle of Outrage, as “an existential outlaw.”

“It was a cardinal rule with all of us,” said Barth. “You’re not a follower. You’re not a joiner. It was part of the ethos.” “Our lives were regulated by a strict chivalry code,” Milius would later say, explaining his brigand’s mindset. “We were samurai.”

Barth considered his friend’s rebellion innocent, unpredictable, and always entertaining. He was once invited to a reception at the Milius house or a group of Chinese diplomats. When he arrived, he saw Milius “sitting cross-legged on the floor, barefoot in his suit, eating a big plate of shrimp.” Although his parents were appalled, they said nothing.

While most young Americans in the early 1960s were preparing for college, marriage, and careers, something dramatically different was taking shape in Southern California. Because Milius and Barth began to surf at young ages, they were “never conditioned in the ways of bourgeois society,” said Barth. Instead of their identities being defined by class, religion, or social status, they were defined by surfing. Moreover, living in the bubble of West LA, they had the freedom to ignore not only mass culture, but the prim dictates of 1950s America. Robert Irwin put an even finer point on it when he described the “footloose” and “freewheeling” attitude West LA teens had had about the post-war world. “From the time you were 15, you were just an independent operator,” he said, “and the world was your oyster.” “We were really good at freedom,” Barth said.

After surfing, Barth, Bass, and Milius often would go to Dave Sweet’s surfboard shop to discuss design with Sweet. “John had a sense of craftsmanship and design which played out not only in surfboard design, but his guns, which he admired for the workmanship and design,” recalled Barth. “He had an eye for excellence for all things, really.”

It was in that showroom on Olympic Boulevard that Barth, who would later become a renowned fine artist, first learned about form and how to take the time to notice and appreciate an object. By high school, Milius, Barth, and Bass all were drawing, painting, and showing artistic skills. “It was a moment,” said Barth. “Innocence and creativity together, creativity born by mistake or by design.”

A surf trip with Milius was an LA version of Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast. Sometimes they went to Star Burger on Lincoln and ate five-for-a-dollar hamburgers. If they were really hungry, the trio went to the Viking’s Table on Pico, home of an all-you-can-eat steam-tray smorgasbord. Although, like Barth, Bass would go on to have a successful art career in New York, it was Milius who was the first of the group to have a one-man show in LA. “John, being John, got to know the owner [of the Viking’s Table] and cut a deal,” recalled Barth. In exchange for an endless ticket to the buffet, Milius agreed to paint various imposing, horn-helmeted figures from Viking lore, which were hung in the dining room.

Milius’ antisocial, surf-punk behavior genuinely began to concern his parents. In an effort to get their son back on track, they sent him to the Lowell Whiteman School in Steamboat Springs, Colorado. Students at the unconventional boarding school were allowed to check out horses and guns and spend their weekends hunting elk and camping in the wilderness.

Years later, Milius credited the wild Colorado mountains with changing him forever. In addition to learning to survive outdoors in the wintertime, he read Melville, Faulker, Hemingway, Kerouac, and Conrad and discovered his own gift for writing. He also found something within himself that cannot be taught: the God-given gift of a great ear. Milius has said he does not just see words on paper. Instead, he hears them in his head.

By the time he graduated from high school, he could mimic the greats and write school reports in “Hemingway,” “Conrad,” “Technical Manual,” or “Kerouac.” He further attributed his Homeric ability to tell stories to surfing’s oral tradition: In the years before heroic feats in the water were captured and documented in print or on video, the only accounts were spoken, shared on the beach or around bonfires by the “existential outlaws” themselves.

“Surfers in those days were more literate than the image the surfers have today,” Milius told Segaloff in Big Bad John. “You must remember that surfers had a great beatnik tradition. The first time that the great waves of Waimea Bay were ridden, Mickey Muñoz quoted the St. Crispin’s Day speech from Henry V [“We few, we happy few, we band of brothers...”] to the other surfers before they rode. There was a different attitude about surfers.”

When Milius left for Colorado, he was a teenager. When he returned to Malibu, he was a large, hirsute, bearish man. He started to notice harbingers of social change at the beach, like “the coming of hippies, the coming of drugs, the Vietnam War, the protests, the commercialization of surfing, the cheap heroes and the real heroes, the loss of morality, the pioneers being forgotten. All of this happened,” he said in Milius, “by the time I was 21 years old.”

Although he was moving up the Malibu food chain, Milius’ attention also began to return to his fascination with aviation. American military advisors were already in Vietnam, and he wanted to become a Navy fighter pilot. In his mind, he would either earn his stripes in the sky over Vietnam or die trying. However, when he went to enlist, a naval doctor discovered that he had asthma and declared him unfit for military service. This rejection left him totally demoralized. “I was going to miss my war,” he said.

Increasingly aware of his own insignificance, Milius was forced to reconsider what he was going to do with his life. In 1962, he moved to Hawaii, rented an apartment near Ala Moana, and surfed the reefbreaks of the South Shore. One day on the beach, he met big-wave legend Buzzy Trent, who was impressed by the talkative young man’s drawings. Trent saw something he liked in Milius and took him under his wing, schooling the wayward youth about a world that was much rougher than the one he’d left behind in Malibu.

Before he arrived in the Islands, Milius had considered himself a tough surfer who was willing to fight anybody. That winter in Hawaii, how- ever, he met men like Trent, Conrad Canha, and the Ah Choy brothers and saw “real violence and real life, and how dangerous it was.” Hawaii hadn’t become a US state until 1959, and gambling and prostitution had been legal well into the 1940s. Given the huge transient military population, corruption and syndicate-controlled vice were still important parts of the economy. In one famous example, when two Chicago mobsters traveled to Oahu to send a message to the Hawaiian syndicate for encroaching on their operations in Nevada, they were executed upon arrival. The syndicate then “returned their chopped-up bodies to the mainland in the back of a trunk with a note attached: ‘Delicious, send more.’” Milius told Segaloff that Hawaii made him realize, “I wasn’t at all what I thought I was.”

The Cuban Missile Crisis climaxed on October 27, 1962, after a Soviet surface-to-air missile, launched from Cuba, shot down an American U-2 spy plane and killed the pilot. The next day, with the world on the brink of a nuclear war, Milius decided to spend the day in the water at Ala Moana. “I surfed for eight hours. The waves were 4 to 6 feet—offshore winds,” Milius recalled in Big Bad John. “I knew what was happening, but where else was a better place to be?”

Although Milius may not have been as tough as he thought he was, during his stay in the Islands, he discovered his true calling: film. One rainy Honolulu day, he stumbled into a theater that was holding a weeklong Akira Kurosawa festival. After watching the great Japanese director’s classics—Rashomon, Seven Samurai, and others—he began to consider a career in filmmaking for himself.

After surfing Ala Moana until after dark one evening, Milius was paddling back to shore, looking at the boats to take his mind off the sharks. He spotted a big, beautiful sailboat whose well-lit deck was bustling with activity and decided to take a closer look.

The Araner was a 106-foot ketch owned by Kurosawa’s idol, John Ford, the four-time Academy Award–winning Hollywood director, who was on his way to Kauai with John Wayne and Lee Marvin to film Donovan’s Reef. Milius paddled over.

“I’d like to hire on,” the young surfer said to a man on the deck. “I’ll do anything.” “Can you sail?” the man asked Milius.

“No,” Milius replied. “But I can dive with the best of ’em, and I can swim really good, and I’m a great surfer, and I really know the sea that way. But I’ve never sailed.”

Suddenly, the man turned and Milius realized he was speaking to the Duke himself. “Well, come back when you know how to sail, kid,” he said.

Then Ford, who was next to Wayne, also turned around.

“Sorry, kid,” he said. “We don’t have any surfing in this movie.”

“Thank you very much, Mister Wayne and Mister Ford,” Milius replied, and went on his way. Describing the meeting many years later in Big Bad John, Milus commented that it was like “a scene out of a movie. That didn’t happen by accident, now did it?”

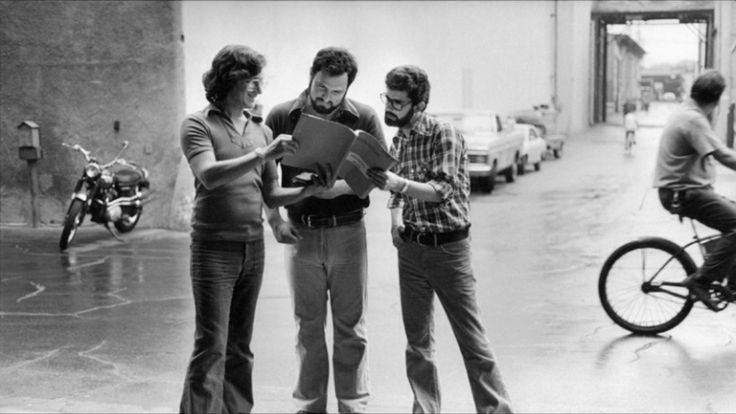

Touched by Hollywood fire, Milius returned to Los Angeles, resumed surfing Malibu, enrolled at USC, and began to study film. Even among classmates and peers like George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, Randal Kleiser, Don Glut, Basil Poledouris, and others who would go on to gain fame and fortune in the movie industry, Milius stood out as the group’s alpha male leader. “John is our scoutmaster,” Spielberg said later of Milius’ continuing influence on the group. “He’s the one who will tell you to go on a trip and only take enough food and enough water for one day and make you stay longer than that. He’s the one who says, ‘Be a man. I don’t want to see any tears.’”

Milius learned to write screenplays from Irwin Blacker, the film department’s most feared professor. The author of 22 fiction and nonfiction books, Blacker also wrote for television shows like Bonanza, Odyssey, and Conquest, and co-produced his own novel, Search & Destroy, for TV.

Unlike many of Milius’ other professors, there was nothing academic about him. “I was never conscious of my screenplays having any acts,” Milius later told an interviewer. “It’s all bullshit. [Blacker] never talked about character arcs or anything like that. He simply talked about telling a good yarn, telling a good story.”

Blacker did not scare Milius as he did most of the other students. Instead, the seasoned and jaded Hollywood pro sparked Milius’ curiosity and interest in “the biz.” “There was something very attractive to me about Hollywood, where you could have your throat cut at any minute, where you could get rich,” Milius explained in Big Bad John, “where you could sleep with beautiful women and be pushed into obscurity in a half a millisecond. That was the real world.”

Living in the bomb shelter under a home in Beverly Glen Canyon, Milius hunted deer in Malibu and worked in Hollywood. After his thesis film, Marcello, I’m So Bored, won best animation at the National Student Film Festival, he was hired by American International Pictures, the legendary B movie studio.

He remained as enamored with surfing as ever during this period. Not only did it shape him into a “physical masterpiece of youth and vitality,” but it also afforded him the ability to “avoid real life and work and questions of life.” However, not everyone in town was impressed by his larger-than-life persona and alternative lifestyle. When Milius approached his neighbor, a literary agent, for representation, the agent scoffed. “I’ve been watching you through this past year,” he told Milius. “How do you ever expect to be a writer? You have no discipline! All you live for is being a surfer and having pleasure and bringing these girls back to your place.”

After writing the The Devil’s Eight (a Dirty Dozen knock-off ), along with The Texans, Los Gringos, Last Resort, Truck Driver, and others, Milius was making a strong counterargument against his neighbor’s assessment, showing great skill as a screenwriter while maintaining an outsize character. Commenting on the latter, George Lucas said in Milius that his friend created a persona “built out of his passion for samurai, for Teddy Roosevelt, for people he admired and things he admired—and that character is very outrageous.” “At the time, we thought it was funny. John thought it was funny,” said Jack Barth. “Everything felt like he was playing a trick on the world. He did everything with a wink.”

In 1971, actor and producer George Hamilton approached Milius to write the screenplay for a film about motorcycle daredevil Evel Knievel. When Hamilton asked Milius how much he wanted in compensation, Milius answered, “I want girls, guns, and gold.” Eager to get him working, Hamilton put Milius up in his Palm Springs house, gave him a gun and a motorcycle, and had his associates introduce him to some women. A few days later, Hamilton called his house manager in Palm Springs to find out about his guest’s progress. When he learned that Milius had done everything but write, he called and warned the screenwriter that if he did not produce the script, the girls, guns, and gold would all disappear. Days later, Hamilton began receiving Western Union telegrams in New York with the script written on them. One hundred and forty telegrams later, he had his screenplay.

Milius was quickly establishing himself as one of Hollywood’s up- and-coming screenwriters, especially gifted at writing dialogue. Although he received no on-screen credit, it was Milius who helped to define the character of ruthless San Francisco cop Harry Callahan in the first scene of Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry, penning his most famous line: “You’ve got to ask yourself one question: ‘Do I feel lucky?’ Well, do you, punk?”

The following year, Paul Newman read a spec script by Milius about a judge in the Old West who held court in a saloon. When the studio approached the writer to buy The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, Milius made them an unusual offer by suggesting two scenarios: The first entailed an extremely high fee for the script alone. The second included a much lower price for the script itself, but with Milius attached as the director, a move he believed was “the only way anyone will listen to you in Hollywood.” In the end, the studio chose John Huston to direct the film and paid the young writer the unprecedented sum of $300,000 for his script.

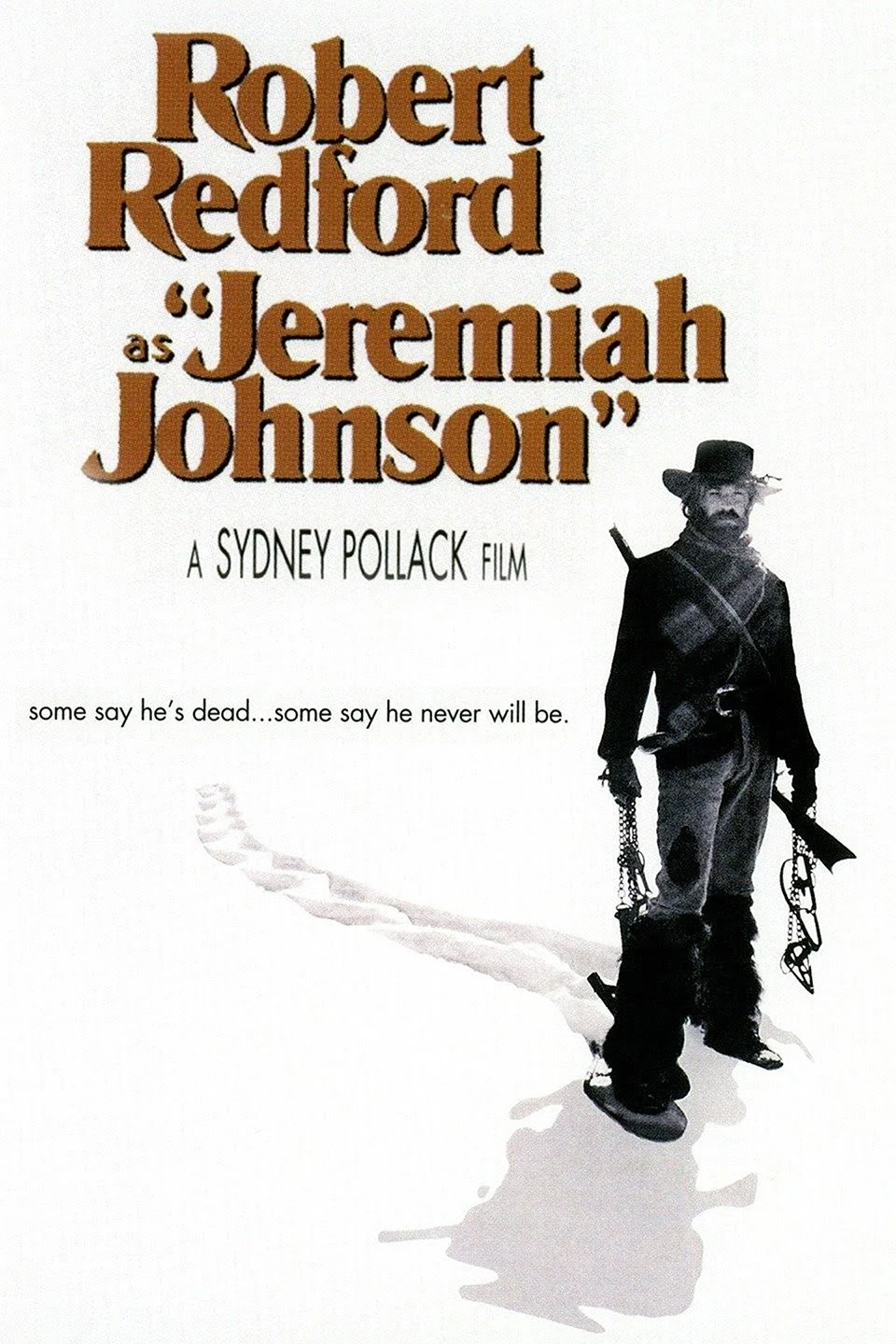

Next, Milius wrote a screenplay about John Jeremiah “Liver-Eating” Johnson, one of the most feared mountain men in the West. According to legend, Johnson had waged a one-man war against the Crow for killing his wife and child. The resulting film starred Robert Redford in the titular role. “Johnson is a classic lone man,” Milius said in Big Bad John, “with a searing loneliness about him. A leader of men is always alone.”

A theme was emerging in Milius’ work: the outsider who lived by his own code of honor and paid a price for it. “I’m Japanese at heart,” Milius explained to an interviewer. “I live by the Kendo code of Bushido. Honor and skill. All my characters have their codes. I like Kurosawa violence, John Ford violence. Violence that takes place within a code.”

“The work that John did,” said Martin Scorsese in Milius, “dealt with something very primal and very truthful to what the human condition is. And he was not shy about expressing political opinions—behavior that was not fashionable.”

Part of this stemmed from Milius’ frustration that Americans, and especially American filmmakers, were consumed by guilt. “I don’t want to see a Western where the Indians are portrayed as peaceful people who worship the sun and birds, and the white men are the only rapists and killers around,” he said. “They were savages and we were savages. We were even more savages than they were.”

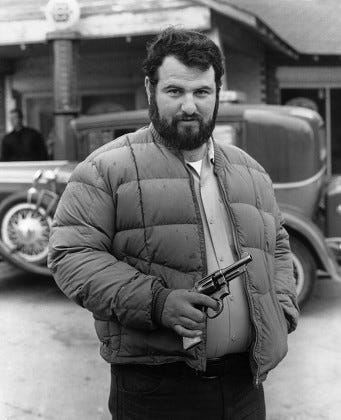

Milius next wrote portions of Magnum Force, the second film in the Dirty Harry franchise. In 1973, he directed his first film, about the In 1973, he directed his first film, about the notorious bank robber John Dillinger. He said he set out to write about Dillinger because he was “a pure criminal” who was not robbing banks “to right social wrongs.”

After the box-office success of Dillinger Milius was hired to write and direct his biggest film to date, The Wind and the Lion, starring Sean Connery and Candice Bergen. Although the movie’s success was overshadowed by Spielberg’s blockbuster hit Jaws, Milius and his peers were taking Hollywood by storm.

Milius, Spielberg, and Lucas meanwhile remained close and were extremely generous with one another’s projects. For example, when Spielberg needed to lend detail and authenticity to Robert Shaw’s monologue in Jaws, in which his character, Captain Quint, recounts his experiences during the sinking of the USS Indianapolis, he turned to Milius, who dictated a 10-plus-minute screed to Spielberg by phone, which was then reworked and shortened into its final form by Shaw.

By 1976, the 32-year-old West LA surfer had worked with Robert Redford, Paul Newman, Sean Connery, Candice Bergen, Clint Eastwood, George Hamilton, John Huston, Roddy McDowall, and Brian Keith. Like Spielberg and Lucas, Milius was considered one of the hottest properties in Hollywood, and, due to their respective successes, each could now write his next ticket. Spielberg would make Close Encounters of the Third Kind. Lucas would make Star Wars. And Milius would make his ode to surfing, Big Wednesday.

By the mid-’70s, while Milius still surfed, he had a wife, children, a career, and all the responsibilities that came with them. He was moving away from the beach—and a new generation of surfers was taking over, with a new style of surfing. The writer and director felt he was watching the end of an era and a changing of the guard. “When you are young and have no responsibility, that’s the time to be a surfer,” he said. “But gradually, the world comes and calls you to other things. You have to go inland, face the whole catastrophe, get married, divorced, have a job.”

Milius felt that the problem with Hollywood’s surfing films, like Gidget, Ride the Wild Surf, and others, was that they were palpably inauthentic. He wanted to capture surfing in a way that only a participant could. “Had I waited five more years, that life would have drifted away,” he said in Big Bad John. “I wasn’t cynical when I made it.” Milius began to meet with his old friend Denny Auberg, a Malibu surfer who would go on to officially coauthor Big Wednesday, to record their memories.

The script was loosely based on the lives and exploits of Pacific Palisades surfers Lance Carson and the Aaberg brothers. Kemp, the older brother, was a lifeguard at Malibu and gained early surf stardom when a photograph of him arching across a sparkling Rincon wall became Surfer magazine’s first logo.

He and Carson, who began surfing Malibu very young, were the two best surfers in the Palisades. The Aabergs lived with their divorced mother next to Palisades Park in a house that was a hive of activity—filled with surfboards, hot rods, and parties. The lifeguards and the best Malibu and South Bay surfers all attended the blowouts, which were as much tribal councils as they were social events. “The kids ran the show at the Aabergs’, and the neighbors were aghast!” recalled Malibu surfer Jim Ganzer.

After Warner Bros. green-lit Big Wednesday in 1976, Milius set out to assemble the cast for the film. Every actor who came in to audition claimed they could surf, but Milius ignored their proclamations.

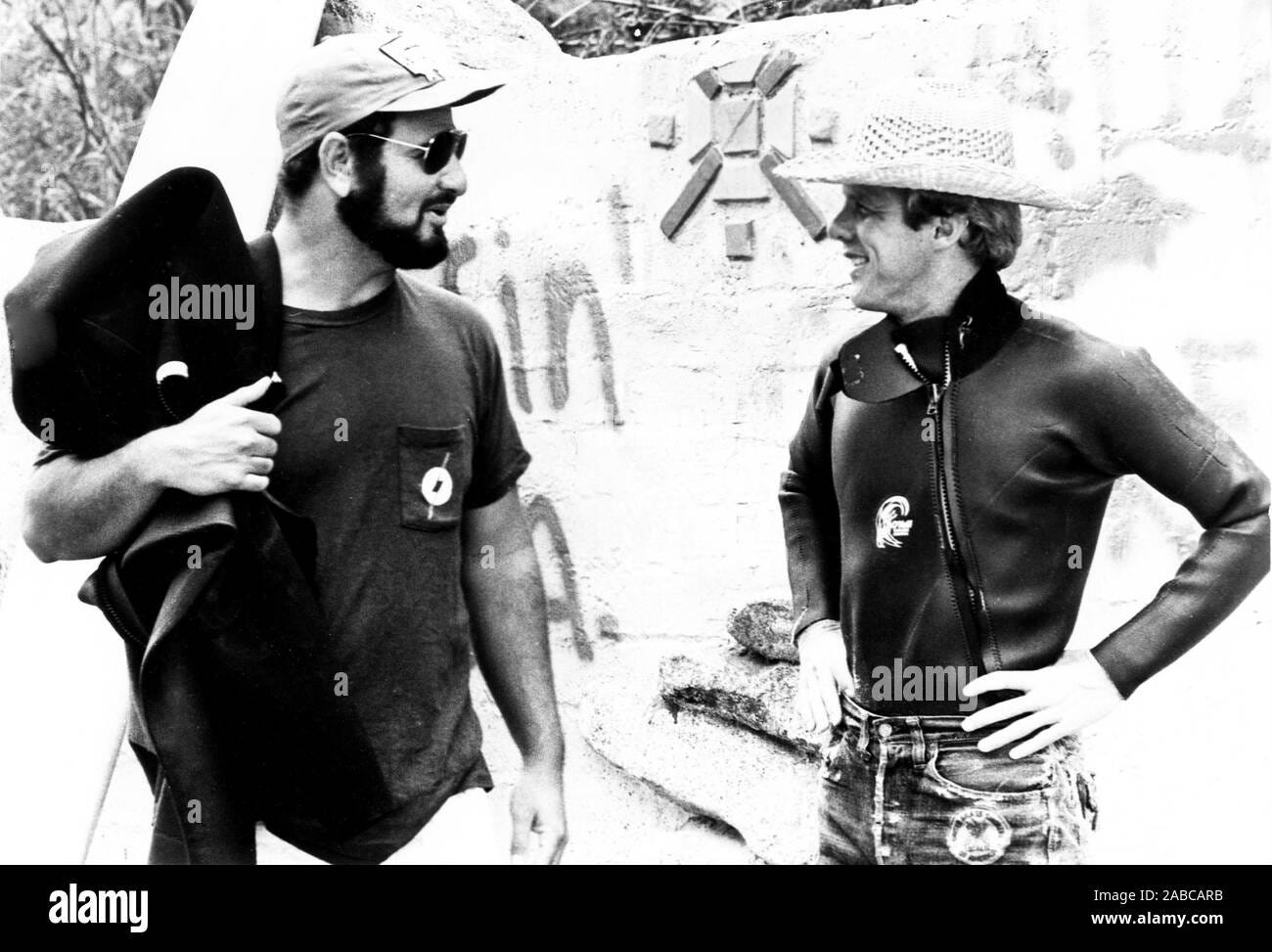

Instead, he focused on putting together an A-team of stunt doubles. That year’s world champ, Peter Townend, doubled for actor William Katt (as Jack Barlow), West Australian Ian Cairns stood in for Gary Busey (as Leroy “The Masochist” Smith), and Kauai’s Billy Hamilton and Malibu’s J Riddle were hired as the in-water talents for Jan-Michael Vincent (as Matt Johnson). Milius also assembled the world’s best water photographers—George Greenough, Bud Browne, and Dan Merkel—to capture their every move on 35-millimeter film.

For more than a year, Surfer and Surfing magazines tracked the production’s progress, reporting from location shoots in El Salvador at La Libertad, at the Bixby Ranch, and on the North Shore. Photographer Art Brewer documented the making of the film for Surfer and described the set as “a full circus.”

“I mean, you had George Greenough in his black-and-white Highway Patrol car,” he said, “burning down the dirt roads and then coming into the lot doing donuts. It was more like a party than a working situation.”

With Robbie Dick and Mike Perry shaping period-correct boards for the film, “The Riddler” stunt-doubling for Vincent, and numerous local surfers working on various aspects of the production, the Santa Monica Bay coconut wireless was humming. Rumor had it that Milius acted like a general on his heavily stratified set. One Topanga surfer working as an extra was summarily fired after he failed to clear the water when the bullhorn announced, “The director requests five or six waves alone.”

When Big Wednesday was finally released in the spring of 1978, not only was it a box office flop, but it also provided an opportunity for what a number of people in the film industry, who’d taken his every hyperbolic statement at face value, believed to be the long-overdue auto-da-fé for Milius, whom they considered a Hollywood heretic. Many, especially on the East Coast, had long resented the success of the swaggering, gun-toting surfer. The New Yorker’s Pauline Kael especially despised Milius and considered him “a bad storyteller” who represented the film industry’s “fascism and amorality.”

After Big Wednesday bombed, Milius felt “scorned,” “excoriated,” and attacked for his hubris. “Ninety-seven percent of my friends abandoned me,” he said. “Not the surfing friends. The Hollywood friends.” Worse than the bad reviews was the fact that the film

was pulled from theaters so quickly, meaning nobody saw it.

As he was licking his wounds, Milius revisited a project that he, Lucas, and Francis Ford Coppola had been developing since the late 1960s, called Apocalypse Now. Screenwriting professor Irwin Blacker had thrown down the gauntlet to Milius and his classmates when they were students by suggesting, “No screenwriter has ever perfected a film adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.” Shortly thereafter, Milius and Lucas used the plot of Conrad’s novella to tell a similarly ambiguous morality tale about American 5th Special Forces Group Colonel Walter E. Kurtz, who goes rogue during the Vietnam War. “It is about a descent to savagery, or an ascent into savagery, depending on how you look at it,” said Milius in an interview. “Kurtz has a line: ‘Yes, I have descended, but I have become much greater for the descent.’”

When Lucas was unable to direct the film, Coppola stepped in and also coauthored the final script. The most obvious Milius creation was William “Bill” Kilgore, the hard-charging surfing lieutenant colonel, played by Robert Duvall, who is reduced to a starstruck fanboy when he learns that a gunner’s mate on a recently arrived Navy river-patrol boat is famous California surfer Lance B. Johnson, played by Sam Bottoms. “One of the reasons I put surfing in Apocalypse Now was because I always thought Vietnam was a California war,” Milius explained to Surfer magazine. “I love the idea of this mighty colonel getting to be a kid again. Of course it’s still Kilgore’s world. He takes Charlie’s Point so the two of them can go surfing.”

During the shooting of the film, Milius sent his old friend Jack Barth, now working as a successful artist in New York, large Xeroxed images of explosions in the jungle and expressed his respect for Coppola. “He loved him,” Barth told me. “He was so impressed with what Coppola was doing to get it made. He’d mortgaged his life and so on.” The feeling was mutual. “Everything memorable about Apocalypse Now was written by John Milius,” Coppola would later admit.

Whatever Big Wednesday’s shortcomings were as a film, Apocalypse Now more than made up for them. It was a smash hit both commercially and critically. Once again, Milius’ dialogue—“I love the smell of napalm in the morning,” and “Charlie don’t surf!”—became part of the popular-culture lexicon, even spawning a song by the Clash.

Change, however, was in the wind in Hollywood. It was apparent at the 52nd Academy Awards when Apocalypse Now, nominated for Best Picture, and Milius and Coppola, nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay, lost in both categories to Kramer vs. Kramer, a film about gender roles, divorce, and parenting that starred Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep.

Through the 1980s, top-earning screenwriters like Milius were subjected to studio executives who insisted on inserting themselves into the creative process. The swashbuckling auteurs of the 1970s like Milius and the patrician studio heads like Frank Wells were replaced by more-compliant writers and directors who took the “notes” of Napoleonic, business-minded executives seriously.

In one meeting, for example, Milius pitched a long, tragic story about a general who is told by prophetic witches that he will one day become king. Lusting for power, he murders the king, turns into a tyrant, sparks a civil war, goes mad, and is finally beheaded. “That’s not a really good story,” one executive said dismissively. As she got up to leave the room, Milius turned to his longtime partner, Buzz Feitshans, and said, “Some people don’t like Macbeth.”

In 1982, Milius teamed with Oliver Stone to write and direct Conan the Barbarian and cast bodybuilding icon Arnold Schwarzenegger to play the titular lead.

In the supporting role, Milius cast his friend Gerry Lopez to play Conan’s archer sidekick, Subotai.

Although the film grossed more than $70 million, critics once again focused their ire on Milius. Roger Ebert called Conan the Barbarian “a perfect fantasy for the alienated preadolescent.” Richard Schickel added that it was “a sort of psychopathic Star Wars, stupid and stupefying.”

Never one to shy away from conflict, Milius wrote and directed a film in 1984 about a fictional Russian invasion of the United States and an American teen insurgency.

Red Dawn was a big hit at the box-office, but the critics again zeroed in on Milius for his “right-wing jingoism.” The National Coalition on Television Violence declared it “the most violent film ever.” “To any sniveling lily-livers who suppose that John Milius,” wrote his New York Times nemesis Maslin, “has already reached the pinnacle of movie-making machismo, a warning: Mr. Milius’s Red Dawn is more rip-roaring than anything he has done before. Here is Mr. Milius at his most alarming, delivering a rootin’-tootin’ scenario for World War III.”

Always someone who defined himself by what he opposed, Milius would embrace his conflict with the liberalism of the cultural elite in the coming years. “I actually like left-wing radicals,” Milius told one inter- viewer. “I don’t like liberals. Whether you’re a right-wing or a left-wing anarchist, you are probably throwing the same bombs.” He rejected the charge that he was a fascist and instead called himself “a man of the people” and “a Maoist” before settling on “Zen anarchist.”

As the film industry continued to change and more power shifted toward the oxymoronically titled “creative executives,” Milius bristled against their attempts to quantify and commodify human taste and the artistic process. “All creative work is mystical,” he said. “How dare they demystify it? How dare they think they can demystify it? Especially when they can’t write. How arrogant it is to assume that you know the market, that you know what’s popular today. Only Steven Spielberg knows what’s popular today. So leave it to him. He’s the only one in the history of man who has ever figured that out.”

Milius found it increasingly difficult to get studio executives, who used terms like “inciting incident” and “four-quadrant potential,” to green- light his projects. Even when he was able to make his films—Farewell to the King (1989), Flight of the Intruder (1991)—he was continually frustrated by the difficulty of the process. As a result, he came to embrace his new persona as a persecuted, “blacklisted” outsider. “I’ve been very, very powerful in my influence on the revolutionary committee,” Milius said to one interviewer, “being that I’m the head of the IWA, the International Writers Army, the terror arm of the Writers Guild. And they have stopped me in many of my projects, and one was to blow up Jeff Katzenberg’s car. This is a symbol.”

Those who knew Milius could differentiate between John the person and John the persona, but others could not. “I know John the person,” said Lucas in Milius, “and he’s sweet, lovable, wonderful, honest, very loyal—great guy. He created this persona.” “John was very rebellious, and in a way he’s one of the few people whose rebellion had consequences,” said Barth.

Producer Andre Morgan best described the impact Milius’ intemperate outbursts had on his own career during the 1990s: “He showed a certain naiveté, which is also fundamental to John Milius. He doesn’t realize that executives with little talent have long memories.” Actor Sam Elliott put it more bluntly: “If you say enough shit or do enough shit, as in the case of Milius, you’re bound to pay at some point, on some level.”

Although Milius continued to make films, he wrote more than he directed. In addition to penning the screenplays for Geronimo: An American Legend, Clear and Present Danger, and Texas Rangers, he also added memorable, uncredited lines to Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, The Hunt for Red October, Saving Private Ryan, and Behind Enemy Lines. He also never missed an opportunity to rail against the neoliberal elite.

During the summer of 1993, I was finishing my PhD dissertation in a shack on the hillside between Topanga and Big Rock. After a close call with marriage in 1990, I was leading a monastic life that consisted of surfing, scholarship, swimming, and martial arts. During the 1992-93 academic year, I’d surfed Nova Scotia and Oregon in the fall, Rincon, Jalama, Sunset Beach, and Hanalei in the winter, then both the eastern and western coasts of Australia in the spring and early summer.

One morning, before the men’s open Jiu Jitsu class at Rickson Gracie’s academy on Pico Boulevard, I fell into an easy conversation with a friendly Hawaiian surfer who knew a lot about surfing big waves. After class, I asked Gracie’s assistant who the Hawaiian was, and he told me it was Leonard Brady, whose articles I’d grown up reading in Surfer.

Brady and I soon became friends—but when he told me that he worked as John Milius’ assistant, I winced. I was the product of extremely left-wing schools (Bard College, then Columbia University) where “film” meant Jean Renoir’s La Bête Humaine, Adolfas Mekas’ Hallelujah the Hills, or similar. Hollywood was considered beneath contempt, and it was a known “fact” that John Milius was nothing less than a right-wing crank, perhaps even a “crypto fascist.”

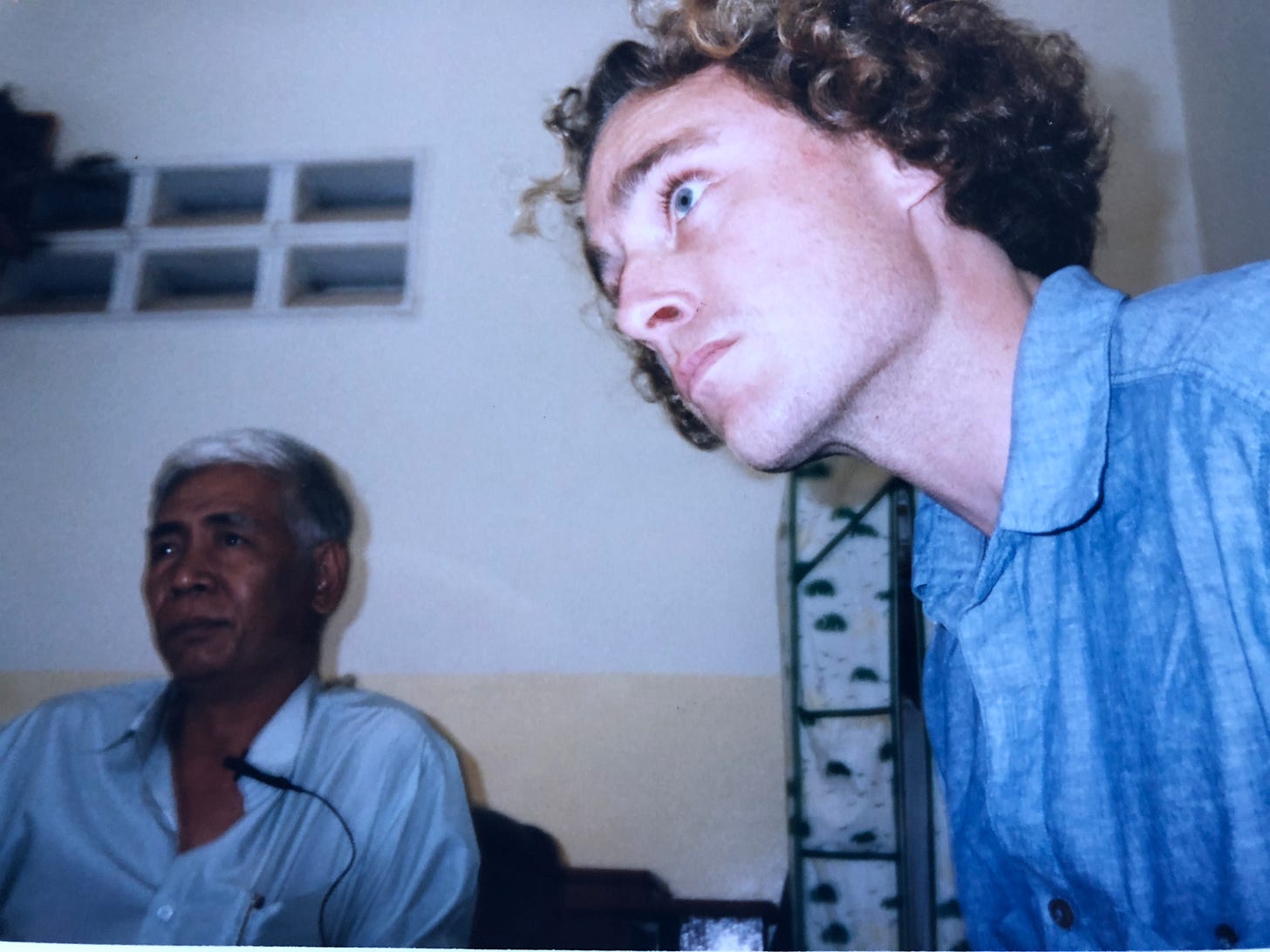

When Brady invited me to visit Milius’ office on the Sony lot to meet John, I initially begged off. Brady, however, was quietly persistent, and before I left for the isolation of the Oregon coast, I drove to Sony Studios, parked, proceeded on foot past the sound studios to the Gable bungalow, then followed the smell of stale cigar smoke down a hallway to door number 105. I knocked. Brady opened, then ushered me into a museum-like office filled with military, movie, and surfing artifacts. Milius, stout and bearded, rose from his desk, smiled broadly, and greeted me like an old friend. “I bet you want to throw away all of your kickboxing now that you are learning Jiu Jitsu!” he said by way of introduction.

Over the course of the next two hours, we talked about the Nuremberg trials, the raw deal General Yamashita received at the hands of General MacArthur, the relative guilt of General Curtis LeMay, the Sioux war in Minnesota during the Civil War, and, finally, the Sunset-like, open-ocean right I was on my way to surf in Oregon. Milius’ childlike enthusiasm and joie de vivre were contagious. Never once did partisan politics of any kind come up. When he learned that the biggest board I was taking to Oregon was an 8'4" Dick Brewer, he insisted that I take his 10'0" Gerry Lopez pintail.

I returned to LA a few months later, triumphant. In Oregon, I’d ridden the biggest wave that I’d ever ride in the continental United States, and, two weeks later, in New York City, I’d successfully defended my PhD dissertation and was awarded the highest honors. Milius had read a copy of my dissertation and was effusive with his praise. “This will be a big book,” he predicted.

I told him that while Harvard University Press was reviewing my dissertation for publication, I was headed to Cambodia to document war crimes perpetrated by the Khmer Rouge. Suddenly, his demeanor changed.

“Why?” he asked.

“Because the UN has failed to do it,” I replied.

“Jesus,” he said with concern. “They’re still fighting over there.”

This did little to settle my nerves. The Khmer Rouge had just announced that they would be kidnapping “long-nosed Westerners” as a matter of policy.

I told Milius that my Nuremberg research had led me to Cambodia, quite naturally, because Cambodia had shattered the “never again” promise—which has been circling around the topic of genocide since the Holocaust—once and for all. These were not welcome views during the “human-rights era,” a decade of magical thinking that began after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and ended with an exclamation point on 9/11. Like Milius, I soon would learn that my words had consequences.

When I next visited his office at Sony, in 1994, I was a humbled and changed man. Not only had my first trip to Cambodia been eye-opening, but Harvard University Press had rejected Law and War, my book on Nuremberg. It was at this point in my career that Milius became a loyal and supportive friend who implored me not to tone down my book, because I was right, and to “never compromise excellence.”

I spent much of the next decade investigating Khmer Rouge war crimes, POW/MIA cases, and lost Montagnard armies, and working as a defense contractor.

I often passed through LA on my travels and always tried to visit Milius. Sometimes, I added Khmer Rouge artifacts to his office/museum’s collection. More than anything else, I was always struck by his generosity. Just as he had helped Schwarzenegger, Lopez, and Quentin Tarantino in their respective careers, Milius helped me.

When he found out I was writing about the Sioux, he introduced me to Sioux chief Bob Primeaux. When he learned that I was traveling to the Montagnard camps on the Vietnamese border, he introduced me to MACV-SOG sniper John Plaster. After I’d found and interviewed the Cambodians who’d captured the three Marines left behind in the Mayaguez incident, he introduced me to Senator Jim Webb. With Milius, there was never a quid pro quo or an expectation of payback—only genuine respect, pure enthusiasm for what I was doing, and honest magnanimity. The better I got to know him, the more difficult it became to reconcile John Milius the person with John Milius the persona.

The new millennium was not kind to Milius. In 2003, the LAPD arrested his longtime accountant, Charles Riedy Jr., for embezzling $3 million of Milius’ money, leaving him almost broke. Before he could recover any of his equity, his accountant died. When it came time for Milius’ brilliant son, Ethan, to go to law school, Milius asked producer David Milch for a staff job on his hit TV series Deadwood to pay for it. Milch did not want to see his old friend reduced to “the writers room” and paid the law school tuition instead. (Milius repaid the debt in full, and today Ethan is an LA County Deputy District Attorney.)

Always stoic, resilient, and optimistic, Milius continued to write for television and worked diligently on his next opus, Genghis Khan. In 2009, when I was finishing my book Thai Stick, I showed him the first draft. He expressed enthusiasm for developing it into a television series, and he, Leonard Brady, Milius’ longtime agent and friend Jeff Berg, and I discussed collaborating on the project until disaster struck in 2010.

In a reversal of fortune that would have strained the imaginations of Homer or Hesiod, Milius suffered a stroke, robbing him of his greatest gift: his voice. “I’m talking about one of the greatest raconteurs of my generation losing the ability to speak,” commented his dear friend Spielberg. “It’s the worst thing that’s ever happened to any of my friends.”

After the stroke, Milius recovered physically and mentally, but the great orator was gone forever. When I finally was able to see my old friend at his apartment in West LA, he immediately recognized me and greeted me with a hug. I’d brought a scrapbook of photographs that he’d seen over the years, and pointed to a picture of a group of young Khmer Rouge soldiers that included a man who’d admitted to me that he’d killed thousands of men, women, and children by hitting them in the back of the neck with an ox-cart axle. Then I showed him a picture of a camp full of Montagnards who’d refused to surrender to the Vietnamese and continued fighting them until 1992.

Finally, I showed him pictures of the combat rescue boats (GARC) that his beloved Big Wednesday cameraman George Greenough and I had invented, built, and sold to the US military. The photos were of the craft parachuting out the back of a C-130, like Milius had predicted many years earlier that they would.

In the old days, each of my stories would have sparked a story of his own. Now he could express himself only with his face, his hands, and a few words.

“Peter Maguire,” he said with a big smile. “Very good!”

I left his apartment happy to see that my old friend was still with us. Although he was battered and bloodied, he was unbowed. Not only did he understand everything I’d said, but the man who’d taken a chance on me was proud of me.

Still, as I walked down Barrington to my car, a wave of sadness hit me. One of the greatest storytellers of the twentieth century had been silenced.