The Twin Towers burning on September 11, 2001. Photo: Stacy Walsh Rosenstock / Alamy Stock Photo

Last week, America’s totally bankrupt mainstream press outdid themselves. Their saccharine, sentimental, yet totally unreflective celebration of the 20th anniversary of 9/11 inspired me to put together a two-part Sour Milk 9/11 Memorial Issue.

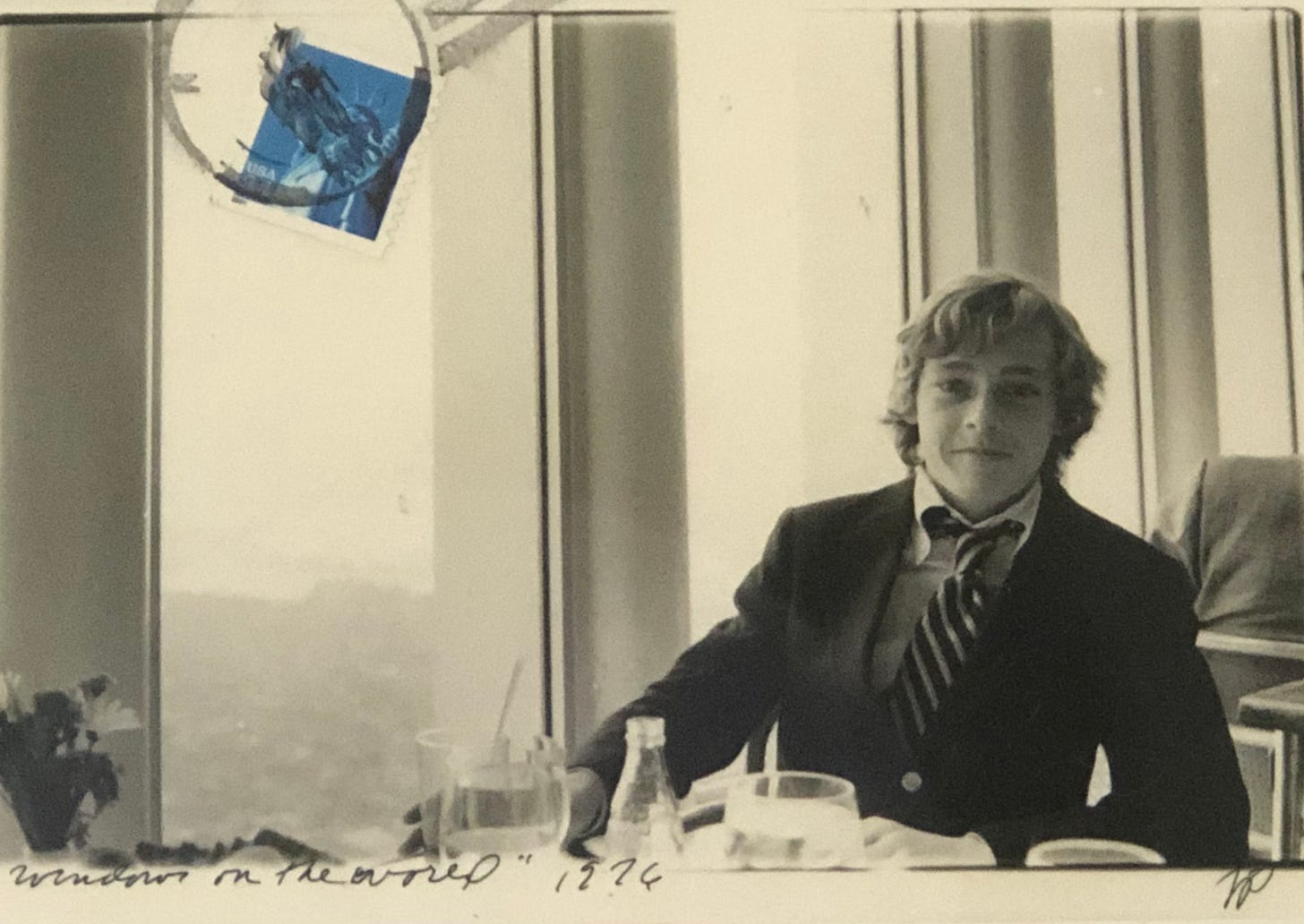

Peter Maguire at the World Trade Center’s “Windows on the World,” 1976 Photo: Jean Pagliuso

We are proud to have my old friend, British journalist Ed Vulliamy, who was at Ground Zero when the Twin Towers fell, as a guest columnist for Part One.

I first met Ed Vulliamy at the “Accounting For Atrocities” conference that I organized at Bard College in October, 1998. I assembled a remarkable group to address a deceptively simple set of questions: Is it possible to enforce the Nuremberg Principles and laws of war without an unconditional surrender and monopoly on military power? Will the U.S. ever be willing to observe legal standards that inhibit America’s strategic options? If attacking civilian targets is a war crime, what does one make of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Tokyo? Finally, were the Nuremberg trials an anomaly in international affairs rather than a new paradigm?

South African judge and first Hague prosecutor Richard Goldstone, former Nuremberg prosecutors William Caming and Ben Ferencz, Jonathan Bush, a law professor who prosecuted Nazi war criminals for the U.S. Department of Justice, journalist Philip Gourevitch, West Point’s Conrad Crane and Gary Solis, South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission deputy chair Alex Boraine, UN Human Rights Commission for Cambodia head David Hawk, Khmer Rouge war crimes investigator Craig Etcheson, State Department War Crimes office deputy Tom Warrick, Hague defense lawyer Anthony D'Amato and others wrestled with the difficult questions that I tabled in my introductory essay, “Accounting For Atrocities Fifty Years After Nuremberg.” [1]

Unlike many of the participants, Vulliamy spoke from his heart because he had been touched by fire. At the Bard Conference, Ed compared himself to the “Ancient Mariner” in Samuel Coleridge’s poem of the same title and added, “Poor sod, he just wanted to enjoy himself, have a drink, meet the bridesmaids - but got pinned to the wall by this old git with his tale of woe.” While the United Nation’s Sergio DeMillo was enabling the Khmer Rouge during the UN’s occupation of Cambodia, Ed was discovering and exposing the Serb atrocities. Vulliamy, not DeMillo, was the one who was really “chasing the flame.” For these efforts, Ed was denounced by many of his journalistic peers for testifying as a prosecution witness in nine cases at the ICTY in The Hague (including those of Radovan Karadžič and General Ratko Mladić) and even accused of fabricating his account of Serb atrocities by Noam Chomsky and his acolytes.

Only one conference participant, Aryeh Neier, the co-founder of Human Rights Watch, president of George Soros’s Open Society Institute, and the leader of what David Rieff best described as “the international legal internationale,” refused to address the questions that I posed. To the Don Corleone of the nascent human rights industry, these questions bordered on heresy. As far as Neier, and the many others who were embarking on careers in the rapidly growing field of human rights (in unlikely places like New York City, New Haven, and Cambridge) were concerned, these matters were settled. The post-Cold-War world would be governed by an international criminal court with “universal jurisdiction.” At the time, some of us who were actively reporting on war crimes and investigating them in the field were growing increasingly uncomfortable with the human rights industry’s evangelical tone and zeal. While Ed, our mutual friend David Rieff, and I believed whole heartedly in legal accountability, we never turned a blind eye to the limits of the possible. [2]

Then came 9/11 and everything changed overnight.

By Christmas of 2001, many human rights industry foot soldiers had made Clark Kent-like transformations into “terrorism experts”—without leaving New York City, New Haven, and Cambridge. Now, everyone was a tough guy or a tough girl, and academics who had never been in a fist fight, much less a fire fight, competed to see who could strike the most macho pose against “Islamo-fascism.” Even the experts at Harvard’s Carr Center of Human Rights got on board with the new American paradigm. Michael Ignatieff endorsed torture, began to plot his run for Canadian Prime Minister, and just as David Rieff had predicted, Samantha Power’s doctrine of humanitarian intervention got hijacked by the neocons and provided the intellectual justification for America’s crusades in the “Greater Middle East.” Just as Ed, David Rieff, and I had previously been considered heretics for pointing out uncomfortable truths about international criminal law, the International Criminal Court, and “universal jurisdiction,” after 9/11 we were considered apostates for raising questions about the Bush administration’s dubious claims about Saddam Hussein’s “weapons of mass destruction,” the use of star chamber courts, evidence obtained by torture, and the invasion of Iraq. [3]

By April 2003, Ed was back in Iraq (he also covered the first Iraq war), working on the vast extent of civilian casualties of the supposed ‘liberation’, and the insurgency. He refused to be ‘embedded’ with the armed forces of any invading nation, working – and negotiating – the byways of Iraq alone with a photographer and translator.

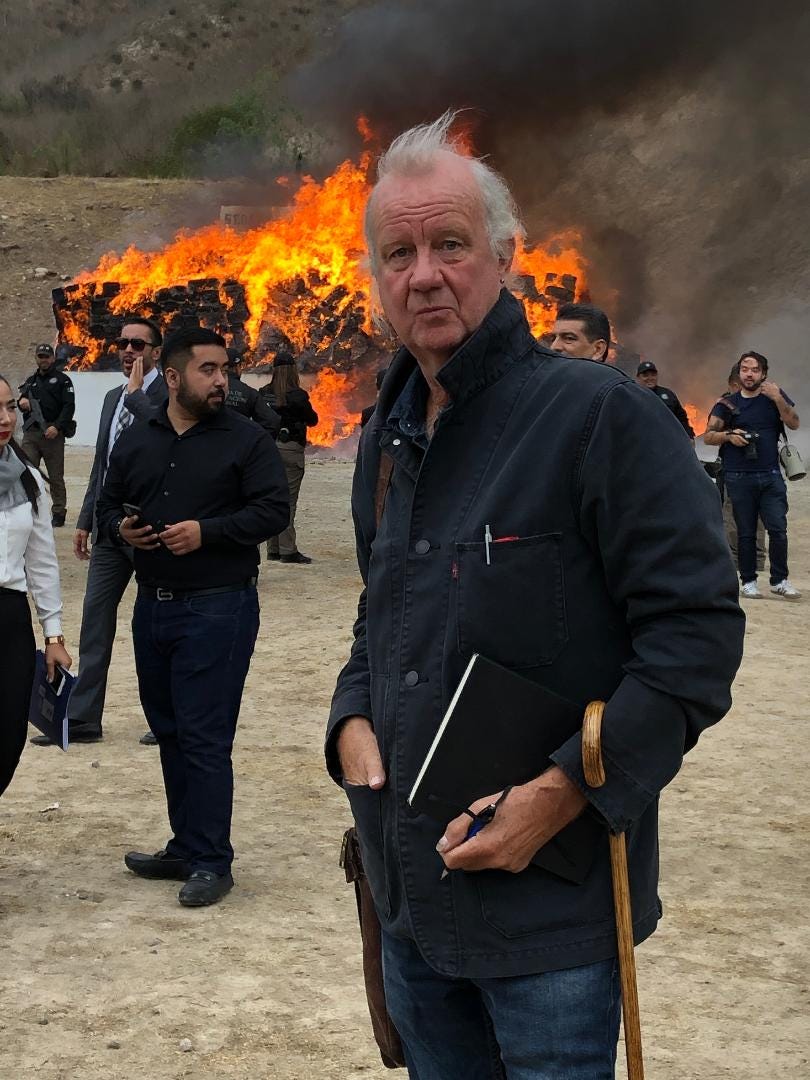

While I continued to work in Cambodia, Ed Vulliamy continued to chase the flame and run risks that few outside of the Spec Ops community can imagine. Ed abruptly changed course, moved to Arizona, and began to investigate the 370 Mexican women who were killed in Juarez between 1993-2005 and discovered a much bigger story. Ed would go on to write groundbreaking articles about NAFTA and migration, the fraudulent War on Drugs, the rise of the cartels, and international banks’ role in laundering the cartels’ blood stained billions--long before anyone else. His book Amexica: War Along the Borderline won the 2013 Ryszard Kapuscinski Award for Literary Reportage and remains the best book on the subject. After a horrific accident that almost cost him his leg, Ed retired from The Guardian and Observer newspapers in 2016 and became a freelancer. In 2018, he published his memoir, When Words Fail: A Life with Music, War and Peace. He is presently finishing up his “an Irish liberetto.” Without further ado, Sour Milk is proud to bring you Ed Vulliamy. [4]

Ed Vulliamy, with the Mexican government burning 26,000 tons of heroin, cocaine, meth and other drugs in the background.

What Happened To The Dust? The Towers Fell, Burying Memory, But Not Money

By Ed Vulliamy

“I think you'd better wake up,” said a voice in my left ear, “the World Trade Centre's on fire.” It was decent of my partner to stir me: I’d stayed out late after a baseball game between the Yankees and the Red Sox had been rained out. I had taken, and remained with, a gorgeous Guatemalan-American real estate agent I should not have been with at all, in my local: Johnny’s Bar, next door to St. Vincent’s Hospital, where I spent most evenings in those days. The bar, not the hospital. The lady and I were getting drunk with nurses and ancillary workers from the hospital, on their way back home to cheaper parts of town. My Swedish partner and I had, of course, fought upon my drunken return and I’d slept on the sofa, clothed, which was just as well. Because within 30 seconds, we were both down on the corner of my block, to behold black smoke billowing from the Twin Towers.

While most people fled from them, we walked towards the burning towers at a brisk pace. Then, just as we crossed Grand Street, the unthinkable happened: in what seemed like slow motion, the South Tower peeled away into itself, crashing down. We broke into a run towards the now single, standing, burning North Tower; something hard-wired propelled me towards it, and hopefully into it.

South of Chambers Street, a police cordon blocked the way, while crowds of people streamed away from the billowing, pale grey dust. Not all the powder was that colour: looking up, we saw what seemed to be flies hurtling into mid-air from the upper floors, not thinking to know what they were. “Look for the splashes of pink dust”, said a colleague from The Wall Street Journal, “hitting the ground like insects on a car windshield.”

I pleaded with a police officer to let me through, brandishing my press card. With a stubbornness for which I’m eternally grateful, he refused me passage and I had just spotted a means of getting past him when an awful sound, like a train rattling from Hell, filled the heavens, as the tower above us crumbled into the dust of its own once-mighty prowess. Only a musician could recall it in sound: my friend John Cale, living right there, said: “hundreds of people running, and not a footstep, for all the dust.”

I had loved the towers. I saw them every time I crossed the Avenue I called home, and measured the time of day by the depth of sunlight on their steel girders: pale towards midday, deep tangerine at dawn and dusk.

The authorities established a no-go area south of Houston Street, barring the public from what was already being called "Ground Zero", as ambulances screamed through this apocalyptic morning. A woman hurled herself at the police line: "My baby's in there! My baby's in there!" By nightfall, St Vincent's Hospital, a block away from my apartment, was taking in the wounded emergency servicemen and women.

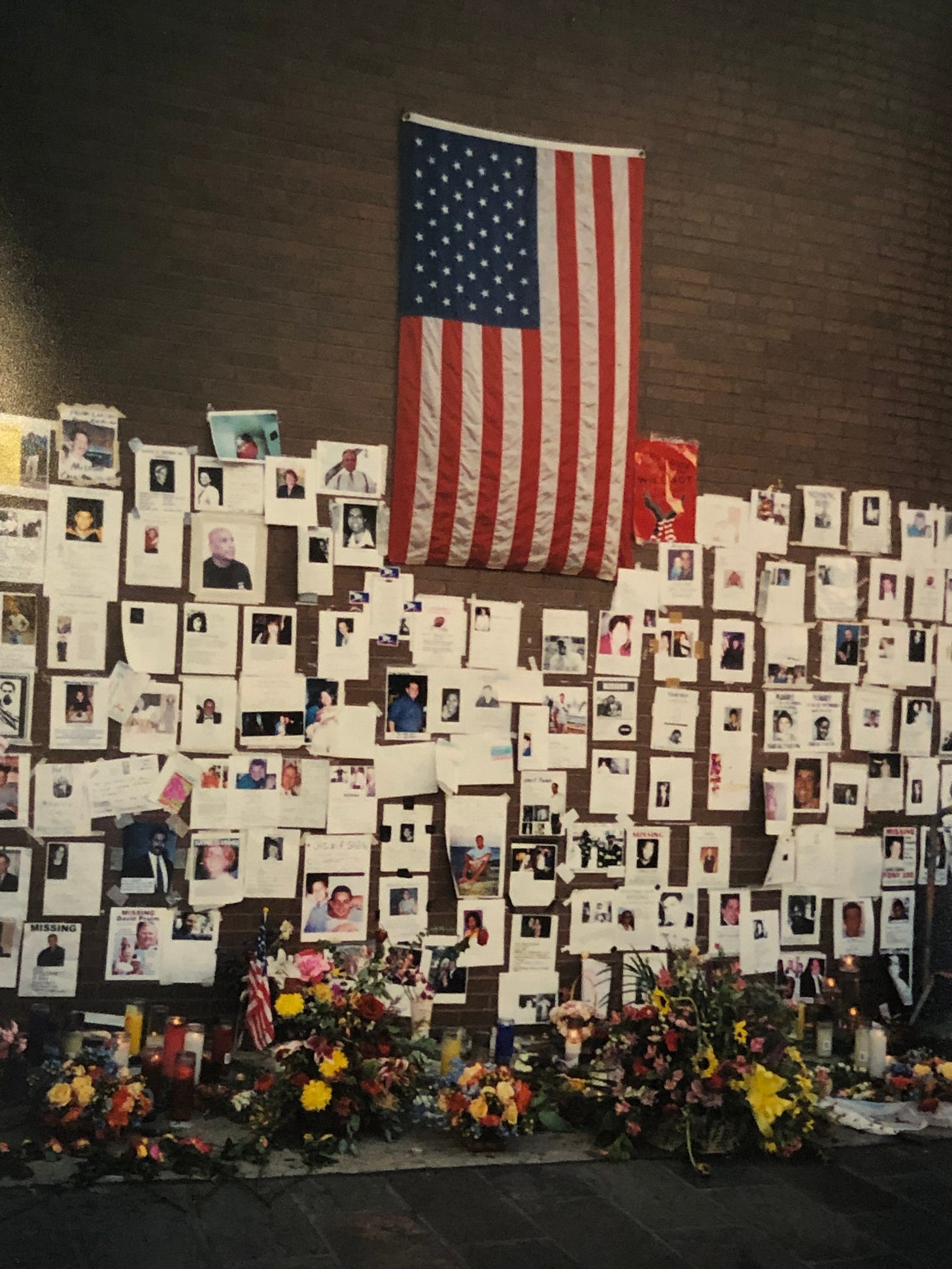

Next morning, Wednesday, what I call "the New York Week" began. There were accounts of thousands of casualties, and the first flyer appeared, attached to a mailbox on the corner of my street: "Missing: Giovanna ‘Gennie’ Gambale". She had a radiant smile and there was a number to call.

By the morning of Thursday 13th, the wall along 11th Street to St Vincent's was covered with similar notices. An inquiry centre for those searching was established across the road from my front steps, in the New School, where a lady called Sara Maddux tried to help Luís Morales with news of his missing wife, from behind a teaching lectern; she told him there was none and offered him coffee, which he sipped in tears and disbelief.

Wall of Missing Persons, St. Vincent’s Hospital, New York City, September, 2001. Photo: Annabelle Lee Carter

Carpets of tributes, candles and flowers formed, one in Washington Square, where I would usually read the papers, and another in Union Square, where I usually frequented Barnes & Noble, but now in which vigils were held, from 12 September onwards. Strewn across these makeshift shrines were gifts people had wanted to leave, for the dead, for whomever, for New York: primal offerings of cigarette lighters, fancy pens, teddy bears, watches and jewellery. Flowers everywhere - lambent colours in the bright September weather. Among the confetti of messages and tributes was one that read simply: “Dónde están las torres?”– where are the towers? Every time we crossed 6th avenue now, we stared, with utter disbelief, at… nothing.

A man’s memorial to his brother, Union Square, New York City, September, 2001. Photo: Annabelle Lee Carter

A paramedic’s uniform, teddy bear, and other memorial offerings in Union Square, New York City, September, 2001. Photo: Annabelle Lee Carter

At the gates to Ground Zero, rescue and emergency services would come up for air. Time and again, firemen were told by their deputy chief: “If any of you have completed your 24-hour shift, please go.” But time and again, they returned to work. A fireman called Stanley - built like a prize fighter with curses to match - from the ladder company right around the corner from my apartment, had over two days lost at least three of his comrades. But when he heard that one missing colleague was safe after all, it was too much for him. He ripped off his helmet and mask, sat on the sidewalk, choked – and wept.

An exhausted firefighter, New York City, September, 2001 Photo: Everett Collection Historical / Alamy Stock Photo

A Brooks Brothers store was converted into a makeshift morgue; what appeared to be pieces of dirt (but were actually shreds of human beings) were analysed, categorised and packaged by people wearing white tunics. Body bags were loaded into refrigerated trucks – mobile morgues. I met drivers of what felt like a funeral cortège of trucks through the Brooklyn-Battery tunnel, hauling the debris to a landfill site called – you couldn't make it up – Fresh Kills.

And at Ground Zero itself, drifts of skin-burning dust covered mountains of mangled metal, rubble and devastation. The determined work made little sound, given its magnitude and scale: teams of “moles” – experts in subterranean work, including a man I knew from years back, Russ Schneider, who looked after the piping system beneath Grand Central Station – joined the search for viable routes through the catacombs beneath. “There are always pockets, like caves,” insisted a fireman called Mel Myers from Ladder Company 103. The ground was so hot that the rubber on the soles of my boots melted. I felt acutely aware that this was a mass grave for people who had done no more, or less, than go to work one morning.

That was the day, and the nobility of New York, I will always remember. But what happened? What is remembered, 20 years on, and what was forgotten?

I noticed one thing at lunchtime on 13 September which – wanting to see the best in my adoptive city - I pretended to ignore. At the corner of 6th Avenue and Houston was an extraordinary scene: this was the outer barrier around Ground Zero, the furthest south the public could go. There, around the tributes reading: “I Love New York More Than Ever,” paramedics would arrive and discharge their stretchers from ambulances, loading other vehicles with the wounded, and body bags. The fire services used this junction for logistics that did not need to be at the kernel of the catastrophe, their workload huge but systematic and strangely calm. But also at this intersection was the Da Silvano restaurant, a favourite haunt of the beautiful people, and why should all this calamity necessitate the cancellation of a lunch date? There they were, around the outdoor tables, casual but expensive blazers across the backs of chairs, chest hair under tailored shirts, elegant legs crossed and stiletto heels flicked by perfect ankles as the laughter and chatter swept the table tops. Heavy beads of grimy sweat meandered down crevices in the firemen's faces; light drops of condensation glided down the outside of glasses of excellent sauvignon blanc.

Everyone was saying that al-Qaida would not cow New York – and they were right. Within a few years, the city supposedly humbled by 9/11 was stage for a very different kind of collapse in 2008 – that of Lehman Brothers and other titans of international finance. Lehman had, come to think of it, given an early clue: in the immediate aftermath of the carnage, it had negotiated a takeover of the Sheraton north of 51st Street, and within a week of the attacks was refurbishing 665 rooms so that 1,500 bankers could get to work, selling stocks, bonds and, it turned out, toxic debt.

In 2010, St. Vincent’s – the ‘hero hospital’ of 9/11, whose doctors, nurses and ancillary staff had treated the wounded, and with whom I’d drink most nights at Johnny’s Bar, next door - was closed for conversion to luxury housing. Condos in those same wards that had hosted the survivors of 9/11 - this was how New York paid its debt of gratitude.

America went to war, of course: justifiably in Afghanistan, outrageously in Iraq. Two decades later, Manhattan has a museum, and Kabul has the Taliban back. Many will see today as a monument to failure.

But what about the monument to the 2,606 dead in New York alone – plus those others that day - for their bereaved families, whose day this really is, on the site of the mass grave itself? The glaringly obvious choice was the haunting steel shard that remained of the South Tower: it could have been secured and stood, in a park upon the site of the fallen towers of which it was itself once part, as one of the simplest and most cogently moving monuments in the world. New York could also have kept the towers of light, which appeared soon after the attacks, spectral ghosts of the fallen buildings.

But the lights were switched off and the shard removed to make way for the mediocre ‘Freedom Tower’. The powers that be were determined that money means more than memory in still marvellous New York.

End Notes

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/1998/10/04/nyregion/the-guide-124079.html; https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/dec/04/karadzic-bosnia-war-crimes-vulliamy;https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/mar/27/i-aws-radovan-karadizic-camps-cannot-celebrate-verdict-ed-vulliamy

[2] The lines separating journalism, scholarship and advocacy grew extremely blurry during the 1990s. Criticism of Nuremberg, beyond the ritualistic complaints about ex post facto law and victor’s justice, was considered to be in bad taste in most academic circles and as a result, analysis of the trials rarely went deeper than American prosecutor Robert Jackson’s opening address. Rather than face profound questions about the relationship between national sovereignty and “universal jurisdiction,” human rights advocates focused their vast resources on procedural questions and legal minutia. This was done in the mistaken belief that trials could succeed where diplomacy and the half-hearted use of military force had already failed. A flurry of diverse and often contradictory international legal activity came in the wake of the Cold War: UN war crimes courts were established; sitting leaders were indicted during wartime; an American court applied the Alien Tort Claims Act and tried Yugoslavian leaders in absentia; the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission traded amnesty for testimony; a Belgian court considered cases against Henry Kissinger and Ariel Sharon; above all, an unsuccessful attempt was made to try Chilean leader Augusto Pinochet.

[3] In his book A Bed For the Night, Rieff pointed out that the neocons and the humanitarian hawks had a great deal in common. “Samantha Power, again, is a perfect example of this. Her book is a call for the United States to impose an idealistic, Wilsonian order on the world --preferably by diplomacy, but by force if necessary. That's why, frankly, I find that critique of the Bush administration by the human rights movement so preposterous. I think, actually, the Bush people have a much stronger case,” Rieff explained in a 2003 interview, “The hard Wilsonianism of a Max Boot or a Robert Kagan is a hell of a lot more intellectually coherent than the imperial idealism, swathed in antiseptic sheets of international law, of Samantha Power and the Soros Foundations. I don't necessarily share the Right's view, but it seems to me it's much more both coherent and honest.”

[4] https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/juarez-falls/;https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/apr/03/us-bank-mexico-drug-gangs;https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/feb/15/hsbc-has-form-mexico-laundered-drug-money;

Books by Ed Vulliamy:

Ed Vulliamy, Seasons in Hell: Understanding Bosnia's War, St Martins Press, New York, 1994.

David Leigh and Ed Vulliamy, Sleaze: The Corruption of Parliament, Fourth Estate, London, 1997.

Ed Vulliamy, Amexica: War Along the Borderline, Bodley Head, London, 2010.

Ed Vulliamy, The War is Dead, Long Live the War: Bosnia: the Reckoning, Bodley Head, London, 19 April 2012.

Michael Jacobs and Ed Vulliamy, Everything is Happening: Journey into a Painting. Granta, London, 2014.

Ed Vulliamy, When Words Fail: A Life with Music, War and Peace, Granta Books, London, 2018.

Ed Vulliamy, Louder Than Bombs: A Life with Music, War, and Peace, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2020.