Marty Sugarman

A Life in Trim

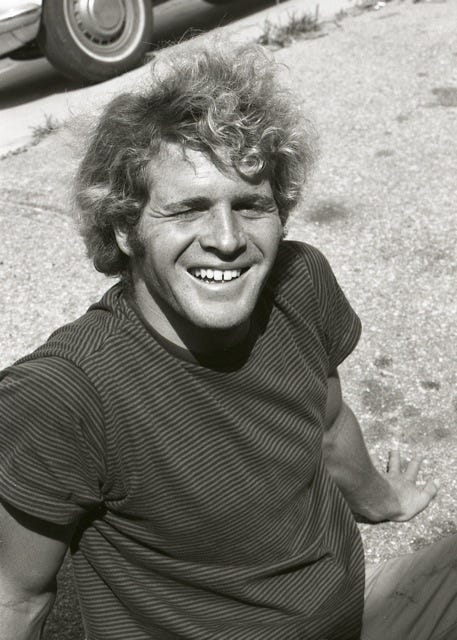

Sour Milk drinkers, what follows is an obituary for my old friend, Marty Sugarman, who passed away in September at the age of 74 after a long battle with Parkinson’s disease. Marty was a world-class surfer, sociologist, and frontline reporter who defined and lived California’s “waterfront culture” long before it was reduced to a marketing cliché used to sell stand-up paddle boards and other detritus of the so-called “surfing lifestyle.” Marty played an important and very positive role at a critical time in my life by encouraging me to take the road less traveled and I am forever grateful.

When I learned that Mary Sugarman died, I made a sunflower lei, and then paddled out at Wrightsville Beach on a surfboard shaped by our mutual friend, Robbie Dick. It was a beautiful, sunny morning and there was a small, clean swell running. One hundred yards outside the lineup, I tossed my lei out to sea and said goodbye to my old friend. As I was paddling in, a beautiful little left came right to me. It was the kind of small, perfect beach break wave that Marty would have loved. I caught it and rode it all the way to shore.

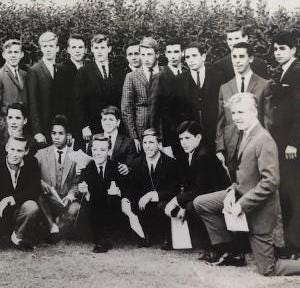

I am a generation younger than Marty Sugarman and don’t remember meeting “the goofy foot Dora,” but he was a presence in the earliest days of my surfing life at Will Rogers State Beach. One of five children who grew up near Westwood, Marty was naturally rebellious and did not follow the path of his older brother, who was a football star and a big man on campus at University High School. “From a very young age,” said longtime friend, H20 Magazine investor and former head of International Creative Management (ICM), Jeff Berg, who met Marty in a 7th-grade PE class at Emerson Junior High School, “Marty had an innate sense of style, taste, and wisdom.”

In addition to being an excellent skier and dancer, by high school Marty was also a standout surfer who edged out legendary Malibu lifeguard John Baker to win the 1965 LA County Surfing Championship.

Although Marty could be found surfing up and down the California coast, his home break would always be Will Rogers State Beach and his heart would always be in Santa Monica Canyon. To Marty, the Canyon was a place where he could “live a life where paradoxes, contradictions, and surrealist thought have equal footing as logic and reason.” British writer Christopher Isherwood, who moved to the Canyon in 1953 and remained there until his death shared Marty’s view, and called it the “western Greenwich Village.” “The entrance to Rustic Canyon begins at the corner of Mesa and Latimer and just up the road a bit is Rustic Canyon Park,” Sugarman wrote in his unpublished book Will Rogers State Beach and Santa Monica Canyon, “It used to be the Uplifters Club. Members of the club, included Will Rogers, Aldous Huxley, and many other eccentrics and the 1920s economic power elite. The club served as a playground for both men and women and poured booze during the years of Prohibition, acting as a hideaway.” Unlike the more staid Pacific Palisades, the Canyon has been home to a vibrant Southern California waterfront culture. [1]

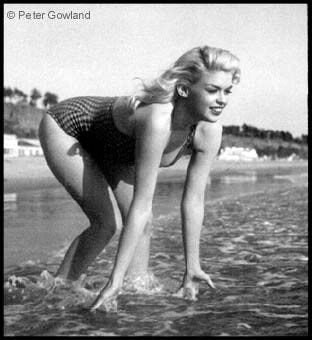

Once a part of the famous cowboy’s coastal ranch, after Will Rogers died it became a state beach and park in 1944. After World War II, actors like Peter Lawford and Marilyn Monroe began to flock to “State.” It was here that Gene Selznick, the first “King of the Beach,” ruled the volleyball courts and just south, down by the green wall was one of LA’s earliest gay beaches. State also served as the plein air photography studio for Canyon resident Peter Gowland who photographed Ann-Margret, Joey Heatherton, Yvette Mimieux, Julie Joan Collins and Raquel Welch at State and nearby beaches. Celebrities like Steve McQueen, Peter Graves, Phyllis Diller, Lee Marvin, and Peter Fonda often frequented Canyon restaurants like The Golden Bull and Ted’s Grill for dinner and drinks because they knew they would be left alone there—nobody in the Canyon would be so uncouth to notice, much less hassle, a celebrity. [2]

While Santa Monica Bay has mostly mediocre beach break surf, it has produced generations of legendary watermen like Pete Peterson, Tom Zahn, Joe Quigg, the Cole brothers, Ricky Grigg, Buzzy Trent, Mike Doyle, and many others. The term “waterman” once carried great weight. A waterman was the maritime equivalent of a black belt in a great martial art. It was not enough to surf. A waterman had to have mastered all the aquatic arts: he was a skilled diver, canoe surfer, oarsman, meteorologist, sailor, ocean swimmer, body surfer, lifesaver, fisherman, spearfisherman, and board/boatbuilder who could ride any size surf on any craft put beneath him.

Marty came from this tradition and always punched above his weight when the pressure was on, like during the 1965 Santa Monica Midwinter Championship. This contest was especially important to some of the competitors because it would decide the winner of the U.S. Surfing Championship. Although he was not in the running for the title, Marty was there to defend his turf. San Diego surfers Skip Frye and Donald Takayama had even flown home from Hawaii hoping to earn enough points to defeat front-runner Rusty Miller. Their plans, however, “were really shaken by Marty Sugarman,” wrote Surfer Magazine, “a relatively unknown surfer from Santa Monica. Sugarman knocked off Frye in a preliminary heat, eliminated Takayama in the semi-finals and then finished first ahead of second place Carroll in the finals.” [3]

Decades before sophisticated surf forecasts and surf cams, Marty could be found most mornings near State’s Tower 18 checking the surf where he often got his first “go out” of the day with friends Terry Lucoff, Robbie Dick, Jim Ganzer, Rich Wilken and others. State Beach was also a favorite of Marty’s surfing mentor, Hungarian-born Mikolos Sander Dora III. Although he was one of California’s greatest surfers, Miki Dora was also surfing’s éminence grise who believed that contests and professionalism “destroy the whole purpose of riding waves.” A notorious conman and thief, Dora traveled the world on a Diner’s Club card until law enforcement caught up with him, and he did a bid in federal prison. In addition to stylish, graceful surfing, Dora taught Marty about scams, capers, misdirection, and subversion. “Everyone was affected by Miki—all of us from POP to Malibu,” said surfboard shaper and former Surfer Magazine editor Mike Perry, “He cast a long shadow.” [4]

As I pointed out in my book, Thai Stick, behavior that today might earn a temporary restraining order or charges of hate crimes was once part of California localism, strange regional prejudices every bit as inbred and paranoid as anything in Appalachia or the Ozarks. There were no surf schools or soft surfboards—you learned to surf by trial and error within a very rigid caste system where “kooks” sat at the very bottom. Even if you graduated from kook to gremmie or grommet (young surfer), you were still relegated to the worst waves, and constantly harassed for the most minor infractions of the unwritten rules of surfing etiquette. If you got in the way or accidentally dropped in on someone else’s waves, the consequences were immediate. It was not uncommon to get slapped, dunked underwater, run over, or “sent in” (kicked out of the water).

Although Dora was also one of the first mean-spirited California “locals,” unlike him, Marty mentored generations of Canyon kids learning to surf at State. “He was nice to groms,” recalled Tony Creed who started surfing at State during the 1960s. This memory is echoed by artist Shingo Francis, who cut his teeth at State two decades later. “He was extremely generous and humble with his time and used to tell us stories about surfing,” wrote Francis, “especially the early years of surfing out front of the Canyon at Will Rogers State Beach.”

Marty gently schooled young surfers like myself on technique, equipment, and above all, style. Unlike the frantic ugliness of modern, aerial inspired surfing, during the 1960s surfers drew their inspiration, not from skateboarders, but bullfighters. “These are values that survived the centuries in la corrida and were picked up by surfers,” wrote U.S. surfing champion and Surfer’s Journal editor Kevin O’Sullivan, “This aesthetic was informed by the concept of sprezzatura, that is, the art of erasing all evidence of effort. It was the art of making the difficult appear easy. Or confidently taking on an opponent with sword drawn, remaining fully composed, showing no fear.” [5]

Perhaps Marty and so many great surfers came out of State Beach because they were hungrier than their Malibu neighbors. “The State guys, although fixtures there, seemed to get around. Marty was more social than some. He’d appear in Oxnard or Malibu or Diego when it was least likely, most unexpected,” recalled Mike Perry, “He’d go out and rip, but in a tightly casual, anti-flamboyant way. THAT was a standout feature of his surfing. I know ex-lifeguards from Zuma who tell stories of Santa Ana days that he was ruling the place, completely alone.”

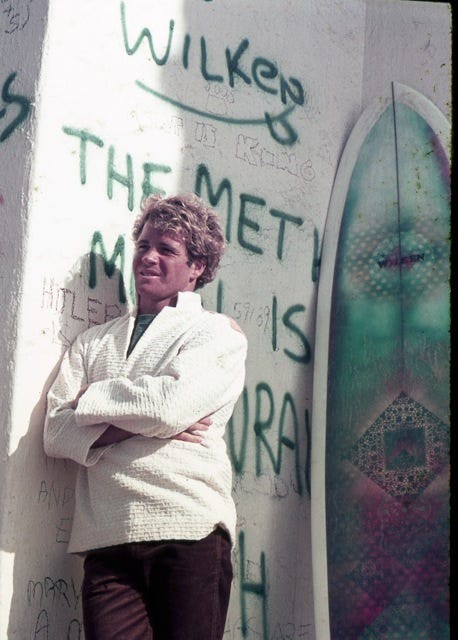

By the late 1960s, Palisades High School graduate Rich Wilken had assembled an impressive team of surfers that included Marty, J Riddle, Robbie Dick, Terry Lucoff, Fred Roberts, Miki Dora, Hawaiians Craig Wilson and Sam Alama, and Glenn Kennedy. “At that point in Southern California, we were more like the ‘skunk works’ of design innovation,” wrote Wilken, “to the others being more the General Motors of mass production of the surfboard industry.” According to the shaper, Marty Sugarman inspired his “Natural,” “Neo Natural,” and “Green Room” models. However, his most famous Wilken was the “Meth Model…for those who like speed.” [6]

After high school, Marty attended college in Orange County for a semester and rented a room in Capistrano Beach from U.S. surfing champion (1966-1970) Corky Carroll. “Marty was a much better competitor than I,” recalled one of Santa Monica Bay’s greatest surfboard shapers, Robbie Dick, “Going to Orange Coast College was probably just a ploy so he could room with his Guru Corky [Carroll]. He had the desire to participate in contests despite what Miki [Dora] would say.” While the waves were often better down south, Marty found life in the more conservative Orange County backward and parochial. “He kept telling me everybody in Orange County were ‘Birchers’ [members of the staunchly anti-communist John Birch Society],” recalled Carroll, “I had no idea what that was but thought it was because the stringers in our boards were made of Birch or something like that. He was much more political than I was and I like to think of him as the ‘Malibu Commi[e].’ Always appreciated his goofy-foot version of Dora style and the fact that he liked to kick back in his darkened room and listen to Donovan albums.” [7]

When Marty returned to West Los Angeles, he attended Santa Monica City College, then UCLA, and got much more serious about his studies. Although he did not quit surfing, he reframed it in non-competitive terms because he did not like the direction the subculture/sport was going. “In the second half of the ’60s, surfing clubs, surfing contests, and manufacturer-sponsored teams were the rage. These activities held out the promise of achieving a social identity (to be someone, something). This required being attached to the various ‘social markers,’ including status and prestige,” Marty explained to The Surfers Journal’s Craig Lockwood, “Here was the beginning of re-making the self-image of the surfer from a free-spirited rebel to a more conventional social actor.”

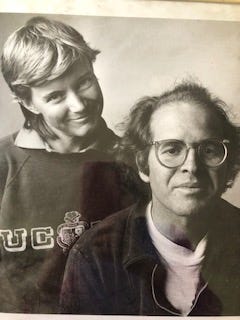

After his first marriage ended in divorce, Marty began dating Mary Jo Johnson, a born-and-bred Malibu girl who would become his muse and partner in crime for the next three decades. One of their first projects was “Go Ride A Wave” kelp shampoo and glycerin soap, next came the Go Ride A Wave t-shirts, shorts, and caps that would become his calling cards. “‘Go ride a wave’ and then shut up about it! This is a very important theme,” said Jeff Berg, “because Marty did not blow his own horn, or extol his own virtues.” [8]

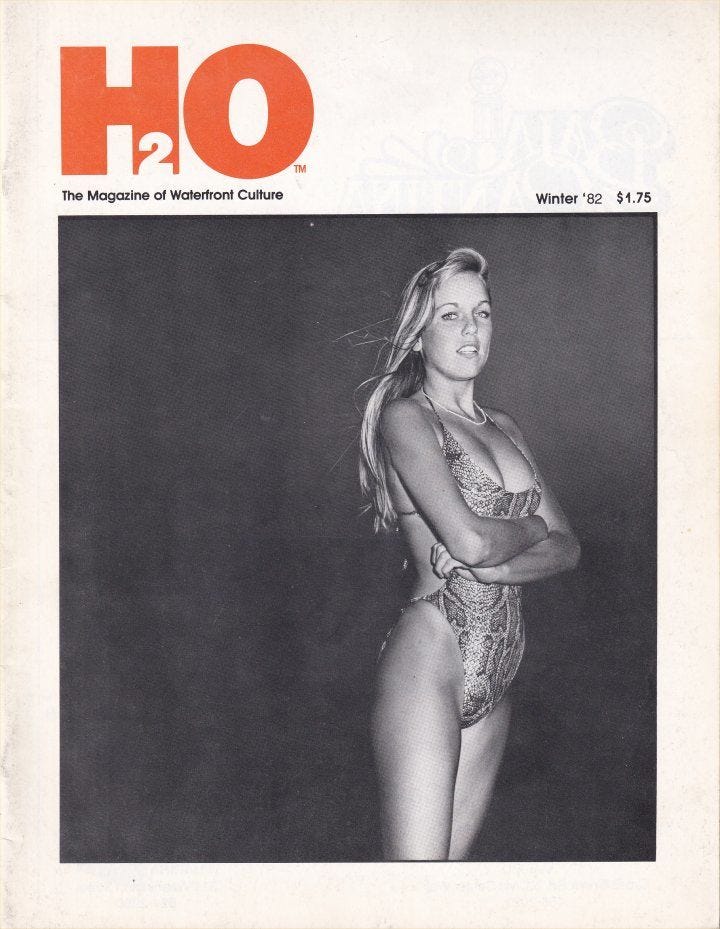

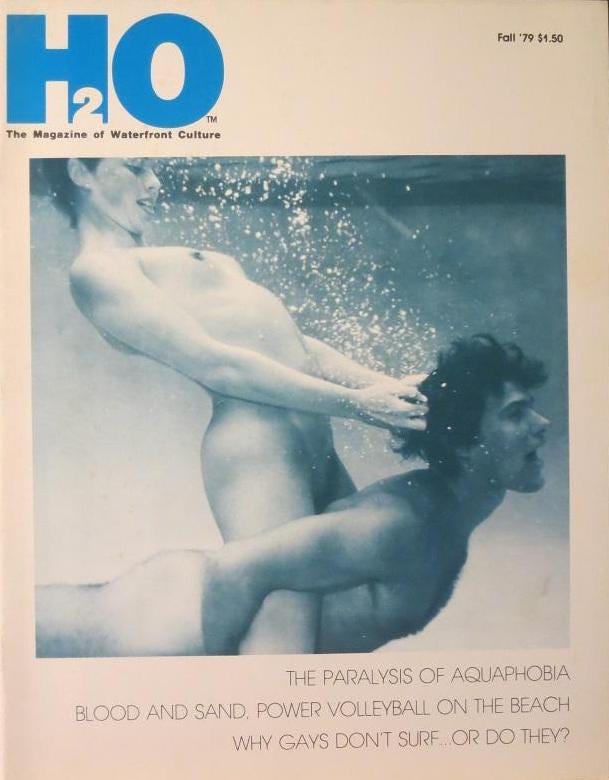

In 1979, Marty and Mary Jo launched their most ambitious project, “H2O: The Magazine of the Waterfront Culture.” Inspired by artist Leonard Koren’s Venice based Wet Magazine, one of the first publications to celebrate LA culture, H20 proudly celebrated Southern California’s “waterfront culture.” Marty best described H2O as a “tribal effort” that explored “waterfront pop culture in short stories, juxtaposing words and images.” It would be more accurate to say that H20 published articles around surfing than articles about surfing. “Some articles and fiction deal with an increasing lack of cultural trust in contemporary rationality which,” said Marty, “tends to reawaken our native imagination and critical thought.” Marty compared Surfer Magazine to Playboy “where every girl is beautiful” and called it “a misrepresentation of the sport” because it “didn’t paint a truthful picture of surfing, because 90% of the time there are no waves. Moreover, they never portrayed the surfer as unemployed or having problems in his life.”

Through his personal connections, Marty was able to draw on a diverse pool of talented writers and photographers that included writers Drew Kampion, Craig Lockwood, Gerry Kantor, photographers Peter Gowland, Anthony Friedkin, Doug Avery, and many more. Marty once called himself in an interview, “the John Cassavetes of the magazine world,” and if that was true, Mary Jo Johnson was his Gena Rolands. “We would have coffee or breakfast,” recalled Johnson, “and then walk up Tuna Canyon, and come up with ideas.” “Mary Jo served as both the conceptual and executional force for many of his projects,” said Jeff Berg. [9]

For a decade, H20 featured articles like “The Paralysis of Aquaphobia,” “Pablo Neruda On the Blue Silence of the Sea,” “Why Gays Don’t Surf, Or Do They?” “Why Chicanos Don’t Surf…or Why Don’t Surfers Lowride,” “Robbie Dick: Shaper as Sisyphus.” The magazine also published more serious and dignified profiles of Santa Monica Bay surfing legends like Tom Zahn, Matt Kivlin, and interviews with Southern California cultural icons like writer Ray Bradberry and historian Kevin Star. Like WET, H20 also did not shirk from the Dionysian aspects of the waterfront culture. “Hey, the sun, the beach, nudity,” Marty explained, “It’s the whole gestalt.” Most H20 issues featured covers and photographs of unpaid, authentic local girls from the Canyon, Palisades or Malibu. Like Gowland, Marty was able to draw out an authentic, untouched beauty. Some posed in bathing suits, like my stunning, statuesque blond classmate Barbara Foster, while others posed topless, and even nude.

By the early 1980s, H2O had grown into a quarterly with a cult following. The Los Angeles Times Magazine described the magazine as “Surfer Meets Granta.” Irrespective of its irreverence, H20 had tapped into something deep in the Southern California psyche. Like Los Angeles artists Robert Irwin, Billy Al Bengston, Ken Price, and Jim Ganzer, Marty un-selfconsciously and unapologetically celebrated West Coast culture without seeking the permission or approval of the East Coast’s cultural commissars. “There’s a culture there—surfing culture, boating culture, diving culture, and artists and writers who care about it,” Marty said, “Look at Herman Melville’s ‘Moby-Dick’ or Henry Thoreau’s ‘Walden Pond.’ A lot of great works of literature have water as an integral part. What’s below the pavement? Remove the city and you’ve got the beach.” [10]

I really got to know Marty in high school during the early 80s when he had his shop/office/salon, Marty’s Cabana, on West Washington Boulevard (since renamed/rebranded as Abbott Kinney Boulevard) in Venice. There he produced “Go Ride A Wave” beachwear, H20 magazine, and conducted research for his Ph.D dissertation in sociology at UCLA. I worked at the Melinda Wyatt Gallery on nearby Market Street and spend many afternoons at Marty’s Cabana talking with him about life, lust mistaken for love, and art. We rarely spoke of surfing because it was something that you did, not something that you talked about. Nonetheless, I often surfed with Marty on winter mornings at State and during the summers at Old Joes.

If I was out surfing Old Joes, Malibu Colony’s localized left where I lifeguarded as a teen, and we saw someone walking in from Malibu, you were honor bound to scream “Beat it Kook!” “Valley go home!” and a litany of other curses at them. However, when Marty and Mary Jo walked around the fence protecting the private beach from the public at 3rd Point, nobody said a word. “He was the only guy we wouldn’t bark at when he walked in from Surfrider Beach because he was surf royalty,” wrote Matt Rapf, my lifeguard boss, “he had an elegant style, the way he held his hands when he rode waves was definitely Doraesque.” [11]

When I was at my surferpunk worst in the early 80s, Marty chided me for being stoned all the time, and encouraged me to get out of LA. Above all, he implored me to take the road less traveled, and not to “become another rich inbred who works for daddy.” Although he did not know it at the time, I was following his advice to the letter. While my high-school classmates were receiving acceptance letters from Harvard, Yale, and Vassar, I was charting a course that would take me to eastern Australia’s fabled sand-bottomed right points, a top secret tube near a shark-filled reef pass in Micronesia, and a giant right in French Polynesia. In order to make this dream a reality, I worked construction jobs in downtown LA, and supplemented my earnings with seasonal work in the underground economy.

Days before my 19th birthday, I flew to the South Pacific, and never looked back. When I returned to Los Angeles in the late summer of 1984 after surfing life-changing waves in Australia, New Zealand, New Caledonia, Nauru, Micronesia, Fiji, Rarotonga, and French Polynesia, one of the first people I visited was Marty. He agreed that I should abort my plan to attend Menlo College and transfer to Stanford. With Marty’s blessings, I applied to Bard College, a tiny, eccentric liberal arts college in New York state that admitted me one week before the semester was set to begin.

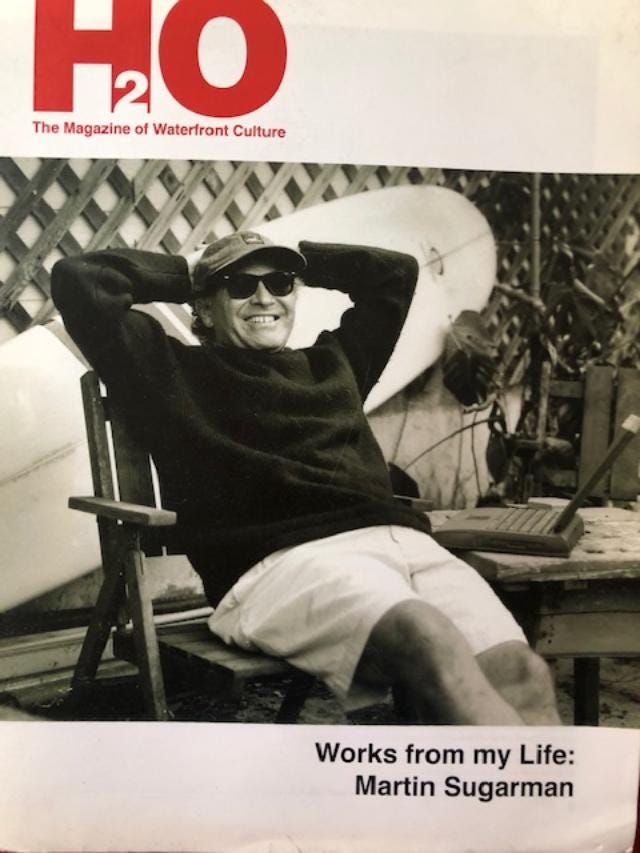

It was around this time that Marty moved the Cabana to West Channel Road in his beloved Santa Monica Canyon where he published H2O, surfed State, and worked on his dissertation. In 1986, Matt Greenfield, who would go on to found Searchlight Pictures, visited Marty’s Cabana and described it well in his high school paper. “The breadth of his interests becomes apparent when you take a look around his small store. There are stacks of literary journals, postcards of people like Sartre and Kant,” wrote Greenfield in “Marty: The Surfing Philosopher,” “stacks of his colorful beachwear, and if you are lucky, a copy of H20: The Magazine of Waterfront Culture, the sometimes quarterly cornerstone of the Sugarman publishing empire. Like the man, the magazine is at first hard to figure. Waterfront culture, after all, sounds like pretty heavy stuff.” To the high school student, what made Marty Sugarman “extraordinary,” was that he is “at peace with himself. He seems to do everything that he desires, and appears to have fun doing it.” [12]

After graduate school, my relationship with Marty came full circle as our professional lives converged on a very deep level. I received my Ph.D in history from Columbia University in 1993 and began working in Cambodia documenting Khmer Rouge atrocities and collecting evidence of their war crimes. Marty had also entered the most intellectually and artistically productive period of his career. After traveling to Mexico and photographing the rural poor, in 1992 he had graduated to the battlefields of former Yugoslavia, and documented the civil war between Serbs, Croats, and Muslims. Rather than spend a decade groveling at the feet of prestigious East Coast publishers to get his first book published like I was doing, Marty stood up Sugarman Productions, and released his first book in 1993, God Be with You: War in Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina. In it, he juxtaposed full frame black and white images of daily life with harsher photographs of war and its aftermath and in the process captured humanity’s good, bad, and ugly in a way that was both personal and humane.

Next, Marty went to Cuba and photographed Fidel Castro’s 40-year-old Marxist-Leninist reign against the backdrop of traditional Cuban life. Then it was on to Kashmir to chronicle life on the frontlines in the military and ideological war between India and Pakistan in Kashmir: Paradise Lost (1994). In 1995, Marty traveled to the world’s highest battlefield, the Siachen Glacier, where he documented the on-and-off war Pakistan and India had been fighting for a decade. In his book War Above the Clouds: Siachen Glacier (1996), he wrote: “Given the fact that two nuclear rivals have gone to war twice over Kashmir, it would be a catastrophic mistake for the world to underestimate the growing risk posed by this volatile situation. Instead of sitting idly by, those members of the international community interested in safeguarding human rights and freedom—and world peace—ought to intervene in Kashmir to help achieve a just solution.” Marty’s final book, Speak Palestine, Speak Again (1997), combined photographs of daily life in the occupied territories with others of Palestinians demonstrating against the Israeli occupation. [13]

Marty returned to LA for good in the late 1990s and when his old surfing buddy, Jamie Budge, asked him about his decision to end his career as a photojournalist, “he said merely, ‘Yeah. Got tired of it. Missed H2O. Literally and figuratively. I guess,” wrote Budge. By 1999, Marty was living on a boat in Marina del Rey, finishing his Ph.D dissertation at UCLA in sociology and relaunching H20 Magazine. “If you were one of the 5,000 lucky folks who bought the quirky magazine during its first round from 1979 to 1989, you could have waved a copy in the face of anyone who ever sneered at L.A. as a cultural wasteland,” wrote Irene Lacher in the LA Times. “It’s a little more sophisticated,” Sugarman told Lacher, “We’re a lot older now. But it’s cool. The magazine’s cool. Here you’ve got an article on East Timor and an article on the history of the Malibu Surfing Assn. Where else can you find that?” By now, Marty had taken up painting and most afternoons you could find him behind his easel daubing crude rendered people, places, and things on small canvases. One afternoon, when I was extoling the virtues of New York City, he looked up from his easel, gestured expansively, and said, “From the Golden Bull to State, I’ve got it all—this is my Montparnasse!” [14]

Marty completed his Ph.D dissertation and received his doctorate in sociology from UCLA in 2001. Although we discussed me writing an article for H20, I was all consumed by my work in Cambodia at the time. After the military collapse of the Khmer Rouge, Cambodian and UN representatives signed a provisional agreement to hold war crimes trials in 2003. The prospect of Khmer Rouge war crimes trials would have excited me greatly in 1994, but it was cold comfort after 9/11. Like Marty, the gap between the theoretical and the actual that I had confronted during the 1990s was now a yawning chasm.

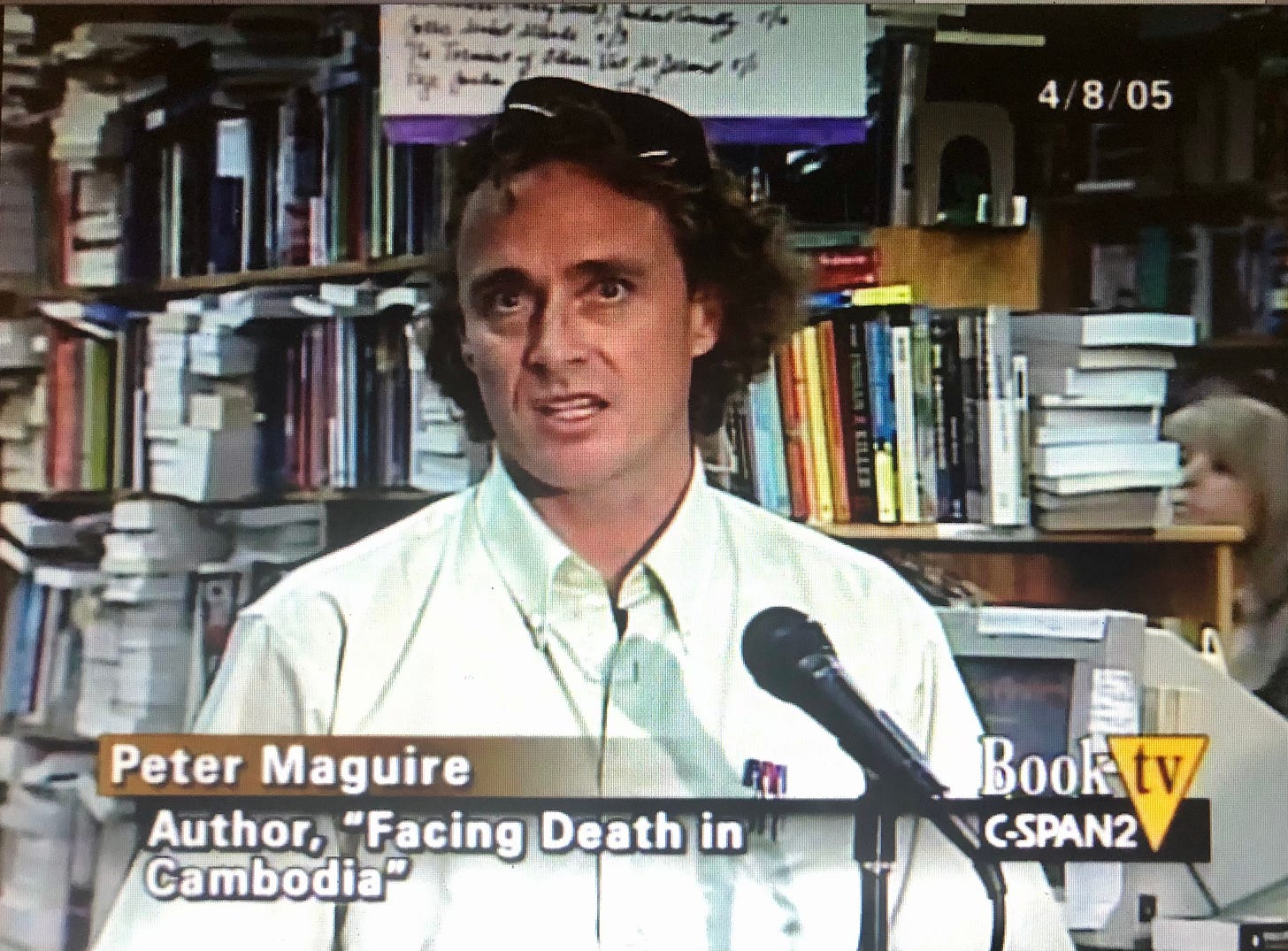

When my book, Facing Death in Cambodia, came out in 2005, Marty attended a book event at Dutton Books in Brentwood and C-SPAN’s Book TV was there to capture this exchange between us.

MS: Personal question. What sparked your interest in becoming an engaged historian?

PM: Curiosity.

MS: Can you elaborate on that?

PM: Ya, curiosity always ahhh, killed the cat, and it always overtook fear, and I was really curious. I wanted to find these guys, I wanted to talk to these guys. I love archival research, I love going to the National Archives, whenever there is a release of new documents, I am among the first people down there.

MS: Why aren’t you covering the Darfur situation?

PM: My pregnant wife.

[Laughs]

PM: No to be honest. Marty Sugarman here has done lots of frontline work. He did remarkable work on the Siachen Glacier and has been in many hotspots equal, if not more extreme than anything I have ever seen. I don’t know, I sort of wanted to get out while I was ahead, I didn’t want to crap out. I’ve had a lot of friends either wind up dead or completely shell shocked and I didn’t really want to join that fraternity. You look into the abyss too long and you are never the same and I’m not the same person I was in 1994. I have less patience for many things.

MS: You’re surfing better than ever

PM: I don’t know, but you’ve seen me surf for a lot of years, Marty!

A few days later, Marty and I met for coffee and he handed me a copy of his book War Above The Clouds. In his inscription, he paid me the highest compliment, “I’m proud of you and what you’re doing for your life.” Because we had both stared into the same abyss where the heart and the mind sometimes part company, we talked openly about the personal toll that bearing witness had taken on both of us. The FBI had recently paid Marty a surprise visit and wanted to talk to him about Pakistan. We were both openly critical of the undefined and open-ended Global War on Terror and were now on the U.S. government’s radar for it. Even though we did not like it, we agreed that if one wanted to be an engaged intellectual, this was the price of admission.

During that same visit, Marty also told me that he was suffering from the early stages of Parkinson’s disease. As always, he handled it with humor. He had survived some of the world’s most dangerous places, and was now the butt of a cosmic joke. As his Parkinson’s disease grew worse, he remained funny, dark, oblique, engaging, and ultimately positive. Although he and his muse Mary Jo had split up, she remained by his side as he struggled with the disease for the next decade. In 2010, Marty moved into the first of many assisted living facilities. He did not last long at most of them and was usually kicked out for going AWOL to visit his favorite haunts with old friends.

What I will miss most about Marty Sugarman is his laugh, his gap-toothed grin, his irreverent wit, and appetite for knowledge, experience, and a good story. “Now that Marty and H20 is gone, and all we have are contests from guys who train and wear tight jerseys, and The Ultimate Surfer,” wrote H20 contributor Gerry Kantor, “all we have is white-bread jock sport it looks like from here on out. The way that Marty integrated surfing with the seamier side of life, was unique to Marty and H20. Gonna miss the sensibility and Marty.” “I will always think of him as an intellectual and ready to go toe to toe on just about any subject with anyone,” wrote Jim Ganzer, “He was also a damn good surfer who I will always see soul arching across a State Beach left in perfect trim.”

Marty you are gone, but won’t be forgotten. Thank you for making a big difference in a young man’s life. [15]

END NOTES

Craig Lockwood, “Sugarman’s Mile of Clean Sand,” The Surfers Journal 23.1, 2014; phone interview with Jeff Berg, September, 2021; Christopher Isherwood “California Story,” Harper’s Bazaar, 1952. During the 20th century, “The Canyon” also provided a safe harbor for European émigrés and noted writers, artists, actors, performers, and bohemians like Billy Wilder, Stella Adler, Arthur Rubenstein, Greta Garbo, Berthold Brecht, Charlie Chaplin, Edward Weston, and others.

“Our Story,” https://inthecanyon.com/our-story/; there was also a vibrant nightlife scene within walking distance from State. The SS Friendship, the bar closest to the beach, was one of the oldest gay bars in LA, and makes a cameo appearance as “The Starboard Side” bar in Christopher Isherwood’s novel A Single Man; Lesley Balla, “The Golden Bull Has Been a Cornerstone for Santa Monica Canyon and the LGBTQ Community,” October 12, 2020: https://blog.resy.com/2020/10/the-golden-bull-has-been-a-cornerstone-for-santa-monica-canyon-and-the-lgbtq-community/

“Pipeline: Rusty Miller Champ,” Surfer, Volume 7 Number 1, March, 1966; Mike Perry from “Tales of Sugey Boy Blogspot”: http://martysugarman.blogspot.com/2011/05/

Jamie Brisick best described Dora: “If you took James Dean’s cool, Muhammed Ali’s poetics, Harry Houdini’s slipperiness, James Bond’s jet-setting, George Carlin’s irony, and Kwai Chang Caine’s Zen, and rolled them into one man with a longboard under his arm, you'd come up with something like Miki Dora, surfing's mythical antihero, otherwise known as the Black Knight of Malibu” from “Requiem for Surfing’s Black Knight—The sanctioned Miki Dora,” LA Weekly, March 2, 2006; Mike Perry from “Tales of Sugey Boy Blogspot”: http://martysugarman.blogspot.com/2011/05/

Shingo Francis and Kevin O’Sullivan, emails to author, October, 2021.

“Rich Wilken’s Story”: https://www.cadamaran.com/copy-of-rich-wilken-1

Robbie Dick and Corky Carroll from “Tales of Sugey Boy Blogspot”: http://martysugarman.blogspot.com/2011/05/

Craig Lockwood, “Sugarman’s Mile of Clean Sand,” The Surfers Journal 23.1, 2014;

WET Magazine was an eclectic combination of sensual nude photos, interviews with avant-garde artists David Lynch and Laurie Anderson, art, photographs from Jim Ganzer, Jacques-Henri Latrigue, Penny Wolin, Herb Ritts, John Van Hamersveld, Matt Groening, Billy Al Bengston, and others; Mary Jo Johnson, interview with author, October, 2021; Jeff Berg interview with author, September, 2021.

Irene Lacher, “H2O Paddles Into Surfer Lit Waters Again,” LA Times, July 2, 1999.

Matt Rapf, email to author, October 2021.

Matt Greenfield, “Marty: Surfer and Philosopher,” Crossroads Crossfire, March 1986.

“Marty Sugarman: Surfer, Artist, Photo-Journalist,” The Palisades Post, August 26, 2010; Martin Sugarman, “Paintings from 2000-2012”: https://gallery169.squarespace.com/martin-sugarman; Martin Sugarman, War Above the Clouds: Siachen Glacier, Sugarman Productions, 1996. Marty made a similar point to The Surfers Journal’s Craig Lockwood: “No need to be sitting in a tabac in Paris smoking a Gauloise and drinking Cinzano and talking to Hemingway about love and death. I’m happy. Santa Monica Canyon’s my Montparnasse. And the Golden Bull is my Le Dome Café.”

“Peter Maguire, “Facing Death in Cambodia,” C-SPAN Book TV, April 8, 2005: https://www.c-span.org/video/?186370-1/facing-death-cambodia

Gerry Kantor, email to author, October 2021; Jim Ganzer email to author, October 2021.