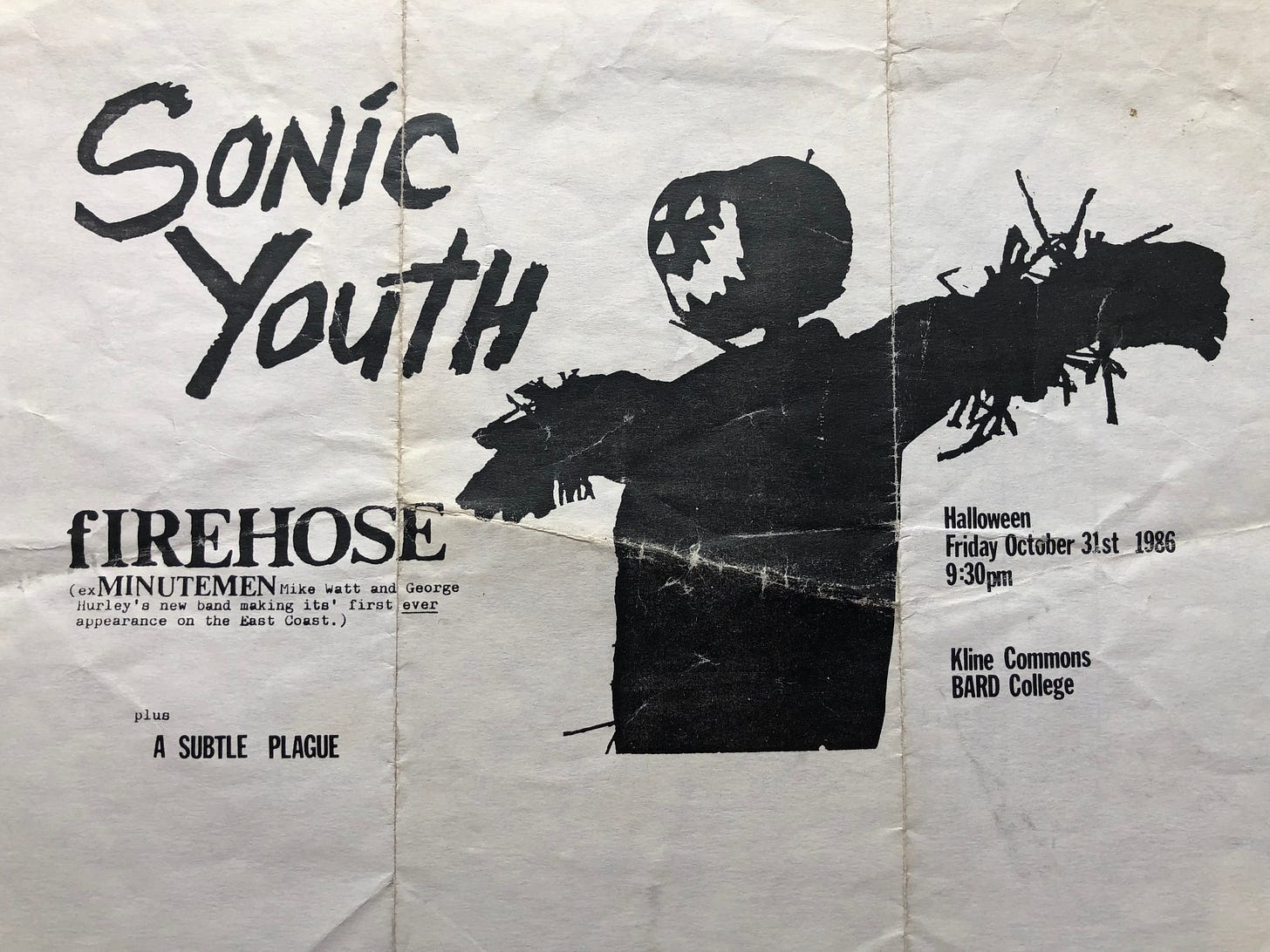

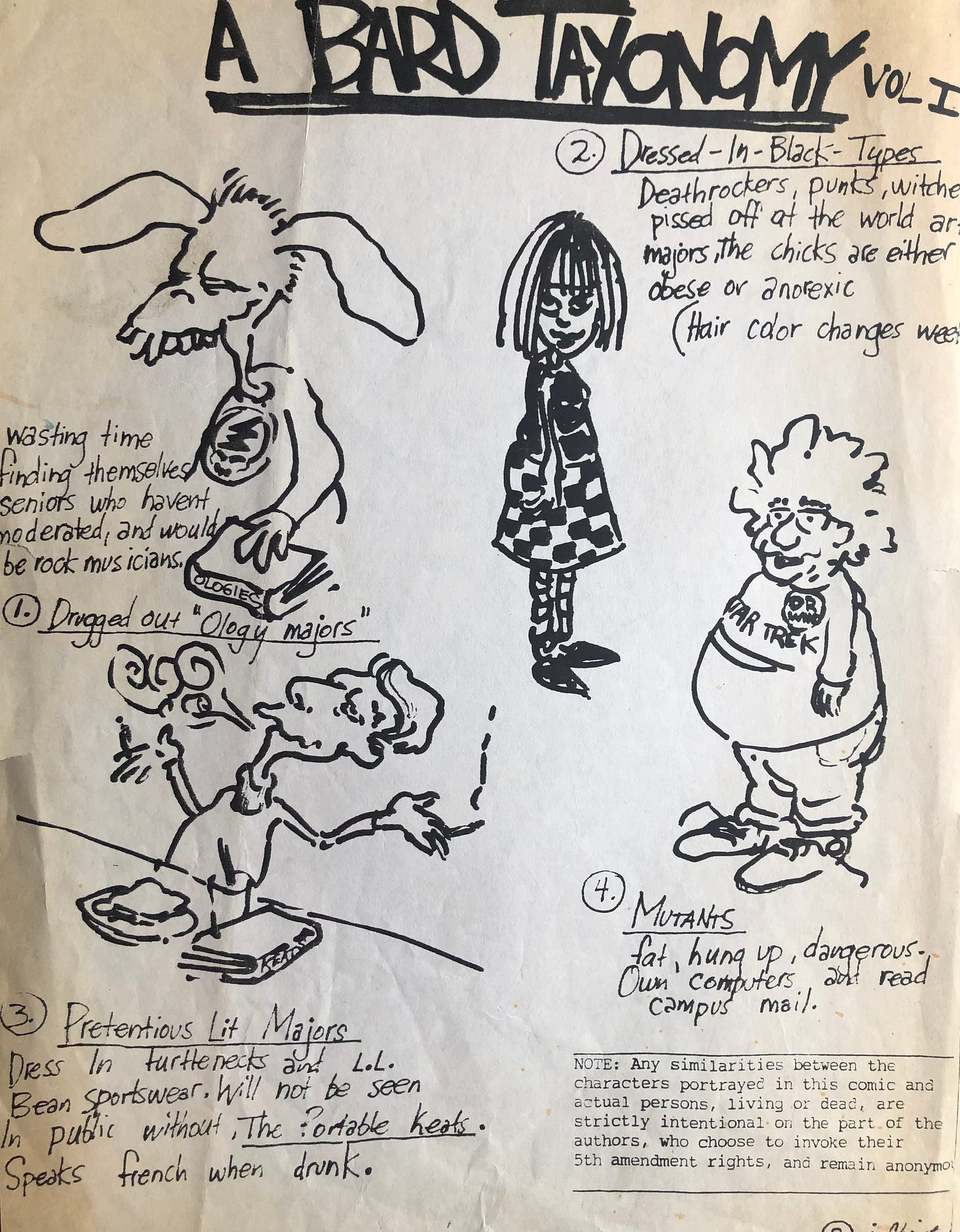

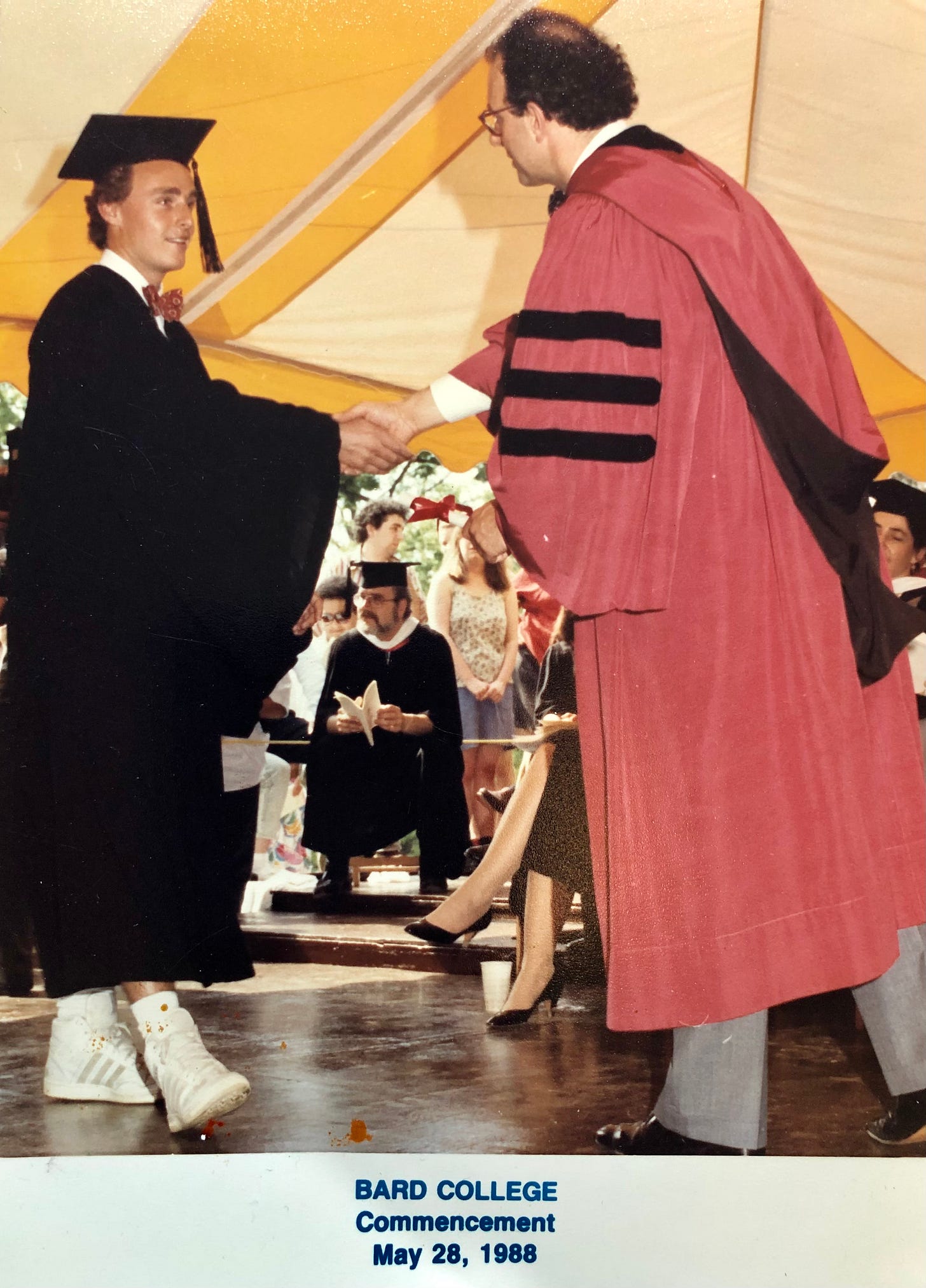

When I entered Bard College in 1984, the school had less than a thousand students, the drinking age was 18, and the bookstore sold rolling papers. There were no “speech codes,” “microaggressions,” or Title IX star chamber courts. Bard had no sororities, fraternities, or gym, and some of the worst teams in the history of intercollegiate athletics. However, we did have great concerts at Sottery Hall and Kline Commons —Sonic Youth, Bad Brains, John Lee Hooker, The Big Noise, A Subtle Plague, Camper Van Beethoven, The Meat Puppets, The Minutemen, Firehose and others—that more than made up for it.

Better than the concerts, however, were the professors. I was educated at Bard, not coddled, pandered to, or indoctrinated. The most important parts of my undergraduate education were the tiny classes and full-contact exchanges with intense and intimidating professors like John Fout, Mark Lytle, Karen Greenberg, Peter Skiff, Robert Koblitz, Tukumbi Lumumba-Kasongo, Sanjib Baruah, Peter Hutton, A.J. Ayer, Gennady Shkliarevsky, Leon Botstein, Michele Dominy, Peter Sourian, Bernard Greenwald, Tom Wolfe, and Jim Sullivan, just to name a few. It was impossible to hide in the smoke-filled seminar rooms because we sat around tables. While all of my teachers cared about my education, they did not care about my ego.

Back then, students were not treated like customers, and if you complained to administrators they laughed in your face. Instead of inflating me with fraudulent and flatulent “self-esteem,” they hammered me on a Socratic anvil. Below is a small sampling of their comments on the “Criteria Sheets” that accompanied my grades:

“You have difficulty in writing critical papers Peter so I urge you to read my comments closely. You lost all clarity towards the end of your paper, and your typos and spelling mistakes got worse. You need to work at constructing an argument very carefully—using language with precision, documenting your arguments, and providing a clear structure to the argument.” —Anthropology professor Michelle Dominy. Grade: C+

“Mr. Maguire is a clever articulate individual. However, his written work began poorly but has improved somewhat…. Mr. Maguire’s papers were consistently marred by awkward writing and trivial but distracting errors.” —Philosophy professor Leon Botstein. Grade: B-

“Although I thought your film review was rather weak, your pieces are generally interesting and lively and, in spite of occasional stylistic lapses, properly written.” —English professor Peter Sourian. Grade: B

“Your oral presentations vary from clever and insightful to vague and confused.” —History professor Karen Greenberg. Grade: B

“Your writing requires more discipline. You need to impose more structure. You lost all clarity towards the end of your paper…Your paper was unusually sloppy, especially the writing.”—History professor Mark Lytle. Grade: B

“The term report is a messy thing—appears to be hurried, defective word processor….The analysis is off the hip, subjective, unorganized, lacks definition of terms and concepts…Judgements are arbitrary, simplistic….The analysis depends too much on subjective morality, inevitably conventional….You can be a student, if you want, even get an education. And you might want one!—It’ll take more commitment, work. But it shouldn’t hurt, and may be very rewarding. And not cut out your underwater life.… I’ve enjoyed having you in class…I do think of you as my tie to plutocracy……” —Political Science professor Robert Koblitz. Grade: A-

“Your capacity to discuss our work and ask questions exceeds the quality of the objects you make.” —Art professor Bernard Greenwald. Grade: Pass.

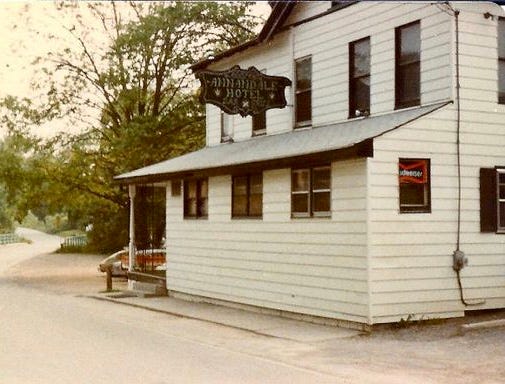

Even though there was an absolute hierarchy in the classroom, many nights I found myself sitting next to professors “down the road” at our only watering hole, the Annandale Hotel, better known as Adolph’s. There we talked, debated, and laughed about books, ideas, art, and current events over shared pitchers of beer and creekside joints. At that time, it was not a capital offense for professors to sleep with their students; some even got married and lived happily ever after. Students were assumed to be adults and treated that way. Some thrived under this regime of absolute freedom, others stumbled, and some simply fell. Bard was not for everyone. Many attended, but far fewer graduated.

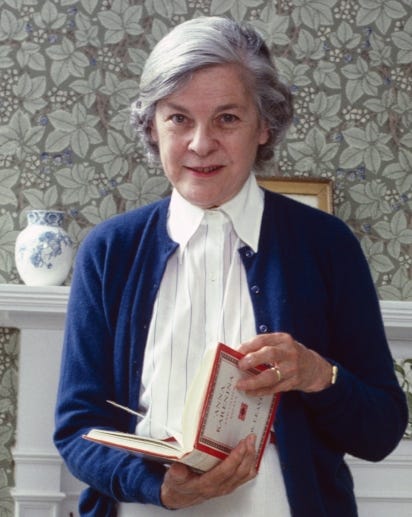

In the fall of 1987, during my final semester, I enrolled in Mary McCarthy’s English literature class, “The Place of Ideas in Fiction.” Always immaculately dressed, the seventy-six-year-old novelist and critic looked like a patrician grandmother. Despite her appearance, she did not suffer fools. I quickly learned that when she flashed her wicked grin, someone was about to get a rhetorical shiv in the chest.

English literature was not my strongest subject. While I enjoyed reading Iris Murdoch’s The Black Prince, Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent, Stendahl’s The Red and the Black, I did not like Henry James’s Princess Cassamassima. When I complained that it was boring, McCarthy smiled her menacing smile, and said, “Perhaps you’d prefer reading detective novels.” One class member, who I’ll call Jane, irritated her because she rarely did the reading and never participated in the classroom discussions. One day Jane walked into class with her hair dyed a strange, new color, and McCarthy said loudly, “Jane,” then paused and flashed that evil grin, and said, “I see you have a new coiffure.”

McCarthy occasionally held class at the “Dutch Cottage,” the house on Annandale Road where she lived with Jim West, her dapper, former-diplomat husband who wore three-piece suits and drove a beautiful Mercedes 280E. One night she had everyone over for class and dinner. One of the students arrived late and when Mary McCarthy offered to take her coat, she said, “No, I’m cold,” but McCarthy wrestled the coat off the girl. There would be no coats in her dining room. She served an excellent baked ham with cloves embedded in its honey-baked skin, and Jim made sure that all of our glasses of Beaujolais Nouveau were kept full. While the other students discussed the book we had read, my friend and classmate, Nick Ayer, and I went into the kitchen and drank with Jim.

After one of my history professors encouraged me to publish my senior project, “Robert Maguire: An American Judge At Nuremberg,” I asked Mary McCarthy to read it. A week later, she invited me to the Dutch Cottage to discuss it. Sitting next to my manuscript on her couch were three small pieces of paper, with page numbers and corrections written neatly in pencil. For the next two hours, she went through the manuscript, page by page, and taught me about the precision and economy of language. “While what you wrote is not wrong,” she said, “you could have said it much better, with far fewer words.” Instead of rushing to publish my good, but immature work, McCarthy encouraged me to attend a doctoral program in history.

Although Mary McCarthy criticized me for my “hardnosed interpretations of literature,” she thanked me for being “a mainstay in the class” and gave me an A. I followed her advice and was admitted to Columbia University. After earning my masters degree in history, I applied to Columbia Law School, Journalism School, and their history Ph.D program. When I asked McCarthy for a letter of recommendation for journalism school, she replied in a letter, “This is a recommendation for journalism school. I think, though, that you might be better off continuing with history and going on to law. The law makes a good foundation for whatever you want to do next unless it’s hairdressing or opera singing.” Even though I was admitted to Columbia Journalism School, I followed her advice and went into the doctoral program in history instead.

In the fall of 1989, Mary McCarthy returned to Bard to teach. A few weeks into the semester she was hospitalized with lung cancer. I drove up to Rhinebeck and paid her a surprise visit in the hospital. When she saw me, she smiled through the oxygen tubes and said, “Well, I’ll be damned.” That was the last time I saw her, and she died on October 25th.

While Mary McCarthy’s class and our conversations were memorable, it was her speech “Useless Freedom,” that she delivered on a cold, October night in the Olin Auditorium that has stuck with me. During the last three decades, this essay and a handful of other essays and books—Orwell’s Politics and the English Language, Animal Farm and 1984, Hans Morgenthau’s Politics Among Nations, Shakespeare’s Henry V, Voltaire’s Candide, Clausewitz’s On War, Edmund Morgan’s American Slavery, American Freedom—I have read and reread. They have helped to anchor me and prevent me from being swept away by a shifting intellectual tide that has replaced critical thinking with critical feeling, and rigor with sentimentality.

Not only did Mary McCarthy’s speech make me a First Amendment absolutist from that night forward, it also made me realize that there were many different kinds of freedom. There’s the timid lamb’s freedom and the bold lion’s freedom. While it is enough for the lamb to be free from the fear of being eaten, the lion’s much more robust freedom works off the assumption that freedom is inherently dangerous. In order to enjoy the lion’s freedom, one must be willing to accept risk because it does not come with a guarantee of safety.

Over the past two decades, many academics and intellectuals have embraced the lamb’s freedom, and their students have paid the greatest price. Their timid perceptions of comfort and safety are now higher priorities than their education. Colleges and universities should not be self-esteem builders where “student success” is guaranteed. I am thankful that my teachers made me earn my success, because it is meritless if mandated.

Useless Freedom

by Mary McCarthy, October, 1987

Insofar as there is a division at this conference on the importance of freedom, I would place myself on the extreme, even extremist side. I am against every kind of censorship—religious, political, moral: I am for the right of Communists to teach and for the right of the Ku Klux Klan to hold rallies. In the realm of civil liberties, that is the simplest position to hold, and one of its great merits is that is does not lead to any sophistry, that is, to the kind of argument heard so frequently in our period in which repression or compulsion is presented as the best defense of freedom and the refusal of a forum to Nazis, say, or to antifeminists is seen as the moral equivalent of planting a tree of Liberty. I am against calling the cops on any occasion short of murder. It follows that I am for nonviolence and resist the division of wars into just wars and unjust wars, favoring the first and condemning the second. It is possible that there are some just wars (and that the last war may have been one), but you will not go far wrong if you proceed on the assumption that there are no just wars and leave it at that. Simplicity is beautiful in ethics as in most disciplines, and a straight line is the shortest distance between two points.

This is not to deny complexity, which, of course, exists too. But the ideal is to avoid it whenever possible, on the analogy of the old Quaker story I once heard told in answer to the supposedly crushing argument of what-would-you-do-if-a-Jap-was-raping-your-sister? Lytton Strachey’s pacifist answer is known (“I would endeavor, sir, to get between them”), but the Quaker’s is nicer. Pirates have captured a ship on which a Quaker worthy is a passenger; they have killed the captain and come swarming over the deck on which the Quaker, arms folded behind his back, is tranquilly walking. He surveys the situation, sees that the pirates are winning; just across his path, the leading pirate, dagger in hand, is overpowering the ship’s mate. Whereupon he slightly pauses in his measured pacing, picks up the pirate from behind, lifts him sturdily up, and drops him into the sea. “Thee has no business here, friend.” Simplicity itself, not a wasted word.

In matters of freedom, it should be even easier, since violence is rarely at issue or only remotely, hypothetically, where control of expression is being argued for. Holmes’ argument that “No man has the right to call ‘Fire’ in a crowded theatre” is of course only a metaphor—what does the word “fire” stand for and where is the crowded theatre? What Holmes is really excluding from constitutionally protected speech is our old friend “incitement to riot.” But this too, though not quite a metaphor, trembles on the edge of figurative speech, and demands further definition: what exactly is a riot and what sort of language would be likely to cause one? The whole problem is there. It is in the interest of freedom, that is, of a free society, that our guardians (in the Platonic sense) be fearless rather than fearful of consequences. Our guardians should not be worriers, which it is the very nature of a censor to be. If we are going to picture our common life in terms of Holmes’ metaphor, rather than worry over what may be dangerous in utterance and what not, it would make sense to legislate for a proper number of exits, stairways, fire escapes, extinguishers, asbestos curtains, and so on. That, too, is a metaphor, evidently, and I will leave it to you to decide what sort of legislation would harmonize with the maximum freedom of expression.

Arguments for more control (i.e., less freedom) at present are not so concerned with the possible menace of physical violence—rioting—as with psychic violence emanating from films, comics, television. This is a parental sort of attitude. It is felt that the populace, particularly its younger and less literate members, is being poisoned by the media. In much the same way as with more reason people imagine they are being poisoned by radiation, acid rain, nuclear waste, food additives, chemical fertilizers, sprays. Often the same people have both preoccupations at the same time and belong to groups that are vowed to “do something” remedial. I notice only one difference. Those who worry about the environment as a pollutant are worried about the effect on themselves—as well as on others, including the whole race—while those who worry about the media are not thinking about the effect on themselves, only on others, the young, the poor, the black. The conviction that the violence in the media leads to crime is shared by the Far Right, the Right, and by a great many liberal Leftists, above all those with a psychiatric outlook. Many of those latter call for some form of censorship, “enlightened” or otherwise. Always for the protection of the weak. And it is natural, I suppose, that a religious man, adherent of one of the fundamentalist sects, would not view his TV set as full of danger to himself but only to those less blessed—the lesser breeds without the law. In the same way, porn on the screen, or in girlie and homoerotic magazines, is frowned on by some liberals as a source of crime. (The first case of this I remember was the Moor Murders in England, where one of the mass killers actually confessed to having been murderously excited by pornography. This was discussed on television, and out of the case emerged a sort of pop moralist, Mrs. Mary Whitehouse, who set herself up as the good fairy of British TV watchers.) But no liberal, naturally, would fear that the nightly TV he watched might make him crime-prone or have any injurious effect whatever, though I think I have noticed some brain damage in friends that seems to derive from too regular watching of the MacNeil Lehrer show.

In any case, assuming that the critics are right and that there is a correlation between porn and mass murder for thrills, between TV violence and street crime, nobody had proposed a remedy that would be efficacious and acceptable to large numbers, to say nothing of civil libertarians. Most Americans, probably most people in the West, have been schooled in the belief that freedom is a sign of political health even if it is accompanied by certain dangers for the more immature part of the population. To guard against those dangers while maintaining freedom would seem to be the ideal to strive for in framing our laws and regulations. Having your cake and eating it: freedom and security. That there are contradictions, inherent in our natures, between your freedom and mine has not gone unnoticed: freedom for the lamb, Blake said, is not the same as freedom for the lion. Do we want a bold society geared to the lion’s freedom or a mild, timid society based on the lamb’s fear of being eaten? I suspect that the great periods in our history—the Age of Exploration, the Renaissance—ages of expansion—have been times of the lion’s cruel freedom, while we, at least the conscientious among us, are bleating through the time of the lamb.

In any case, the prevailing belief among us still holds that freedom is healthy, however hedged about and limited by restrictions. Freedom as the equivalent, virtual synonym of health, not only as upheld in the Bill of Rights, but also in the private sphere. I suppose that in current psychiatry inhibitions are still regarded as bad, repression is bad; the goal of psychoanalysis and, more modestly, of psychiatry, is to undo the wrappings, like grave clothes, like a winding sheet, that bind the free spirit. There is a good deal of Rousseau, if not in Freud, then in post-Freudian doctrine. But if the claims of society are recognized by the happily cured patient, then freedom of spirit is not very often translated into liberty of behavior, always capable of injuring others. I call your attention to the fact that in English we have two words, freedom and liberty, which are not precisely synonyms. One is Anglo-Saxon and somehow folkish, related to such terms as “frank,” “open,” and so on; the other is Latin and pertains to law, in other words, to what can be legislated and codified, embodied in constitutions and declarations of rights. Liberty is freedom formalized. And also formulated. You are dealing with liberty, rather than freedom, when you can cite a numbered article in a code.

Among the enemies of freedom, a new species has appeared in recent years. That is, a kind of Jesuit or casuist, posing as freedom’s best friend. (Judge Bork.) Jesuits, historically, have lined up on the other side, that of orthodoxy, of intellectual suppleness combining with political rigidity. I was pleased the other day when teaching Stendhal’s The Red and the Black to a class to come upon the following, in a scene that takes place among candidates for monkhood in a seminary. Julien Sorel, a new pupil, has just uttered a few words of historical criticism of the Scriptures. “‘To what does this endless reasoning about the Holy Scriptures lead,’ thought the Abbe Pirard, ‘if not to free inquiry (underlined in text); that is to say, the most dreadful Protestantism?’” The old abbe has already reflected to himself on the “fatal tendency towards Protestantism” embodied in the Jansenists of the Church. But to return to today, there are no more Jansenists but plenty of casuists, some no doubt sincere in the concern for souls they express. I am thinking of writers who, like George Steiner, fervently argue that censorship is good for art.

They would admit that freedom of inquiry is a prerequisite for scientific progress. But that is science, and what is true for science, they believe, is not true for art and letters. Examples from the Russian nineteenth-century novel permit them to show, without too much difficulty, that the arts profit from the constraints imposed by censorship. Under the Tsar, when so much utterance was forbidden, the writer was obliged to use a veiled language to express his thoughts—through a seemingly harmless surface, the reader, trained by the times, was able to penetrate to an inner, concealed meaning invisible to the censor. The necessity of this practice, which came to be termed Aesopian language, i.e., fabled utterance, imparted a density, an ambiguity, a doubleness, to those great Russian fictions that is found in no other literature, something cryptic, figurative, “deep”—magical speech. We find this enigmatic quality in Dostoievsky, in Gogol (Dead Souls, The Inspector General, The Nose, The Overcoat), perhaps a bit in Pushkin, but the absence of it in Tolstoy, so fearless of the censor, does not make him the lesser artist. Still, there is some truth in the argument; many instances can be brought forward, not only from past tyrannies and despotisms but from our own time, to prove that humanity owes some sort of debt of gratitude to the censor.

For our own time the argument is slightly altered to fit the circumstances of the Soviets today, where getting around the censorship is the least of the difficulties encountered by an author bent on telling the truth. The chief of these is staying alive, then staying out of the asylum, out of the camps and prisons, avoiding forced emigration, finding some sort of work and housing. There is nothing “Aesopian” that I can find in The Gulag Archipelago, or in The First Circle or The Cancer Ward. Scarcely even in One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Nadezhda Mandelstam does not resort to Aesopian language to write her memoirs. The more classical case, I guess, was Pasternak; Dr. Zhivago is full of cryptic utterance, though not cryptic enough for the authorities.

Nonetheless a distinction is drawn by a critic like Steiner between Soviet literature and our own and the distinction is not favorable to ours. Steiner means dissident Soviet literature, written in emigration for the most part; he regards dissident Soviet literature as a product of the system as much so as official literature, maybe more. I think he is right here and right in placing a high value on the work of the dissidents in and outside Russia. I agree that they are better, on the whole, than “our” writers, whomever you want to name; let us admit that Lenin in Zurich, say (one of Solzhenitsyn’s weakest), is incomparably better than Ancient Evenings.

The reason given for this state of things is our greater permissiveness, to put it coarsely, the lack of gulags strewn about the scene. You can write anything, say anything in America (and in France, England, Germany, Sweden, and so on); the worst that can happen is that somebody will sue you for libel or that nobody will buy your books. But there are other ways of making a living for a writer: foundations, teaching, publishing jobs. Censorship, far from being a hardship, is positively coveted, since it puts a book in the news. The effect—or is it the cause?—of this vast permissiveness is that nobody cares what you say.

There is the difference. In the Soviet Union (and in some of the bloc countries), somebody cares profoundly. The authorities care, the Writers’ Union cares, the Party, the MVD, and because of that the public cares. It rushes to buy out your first big printing; if the censor won’t pass you, it hurries to buy you in samizdat. In the enormous silence produced by official repression and fear, one can hear a pin drop. Your word rings loud and clear. Everyone is straining to hear; no need to raise your voice. A whisper will be picked up by all those extended antennae.

Nothing can be more different from our situation. Nobody is listening; not even the media people, whose business it is to pay attention; sometimes they go through the motions of cocking an ear, but there is too much noise, and if you shout you will only make things worse. The Western artist may come to envy the Eastern artist and idly dream of being jailed for his crimes of opinion. How peaceful it would be —no telephones—how still, and beyond the wall a fellow-detainee could eagerly tap out in Morse or prisoners’ cipher his half of the conversation.

Well, it is true. Beyond the curtain, they are writing for a mighty audience, and we are writing for nobody, with the exception of our poets, who at least are writing for each other and so have no call to envy Yevtushenko; a wish to change places with him would condemn one to having to write his poetry. Our poets are better than theirs, at any rate than the present generation, but that is because somebody reads them, somebody out there is listening—the censor in the bosom of their rival poets.

Yes, it is true. We have a hollow freedom or so it feels to us. But what is to be done? Not even George Steiner can petition Attorney General Meese to ban books for American literature’s sake, ban books to demonstrate their social importance in an unfree society. If Meese were to listen to the argument, he would never yield to its blandishments, suspecting a liberal trap to present him as an enemy of freedom. We shall just have to struggle on, accepting our lot and dimly hoping to be banned someday, somewhere, in a fundamentalist small-town library. Maybe some kind friend could write an anonymous letter, signaling the presence of our book on the shelves.

But let us be serious. No literary person in the West honestly desires to change places with his Soviet counterpart. Such utterances reflect a mood of dejection; our freedom may seem a burden that we would be glad to transfer to other shoulders. Our cherished freedom of inquiry, publication, and so on, can at low moments be seen as the villain, the irresponsible sorcerer’s apprentice behind the awful loss of control of our mind’s products that is the theme of these last centuries: you start with something innocent, such as the doctrine of evolution, and before you know it you have nukes and, if that was not enough, genetic engineering. Once the mind is allowed to poke its nose into nature’s affairs, there is no stopping it and no conceivable screening of results, so that we could keep penicillin and reduced infant mortality—the good side—and reject the rest, such as cloning—awful word. Free inquiry has brought us to the point where we are now, and one cannot deny that there were warning voices; anti-vivisectionists—do you remember?—opponents of vaccination. Maybe cranks, of every persuasion, such as the John Birch League, determined refusers of chlorine in the water supply.

And yet, if we are going to be serious, we are bound to accept at least the benign effects of scientific progress (read free inquiry), that is, to accept the scientific progress we live with in the form, say, of pasteurization without even being aware of it. As for the rest of the package—Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Three Mile Island, Chernobyl—that is past remedy. To halt scientific inquiry at this point would be to shut the barn door after the cow was gone, and nobody, not even the most exalted nuclear disarmer, proposes it.

I myself have never been a great friend of science, at least not of applied science; I could do without airplanes and even automobiles, providing trains and horses were restored to us. I do without cuisinarts, gelatoios, word processors, credit cards, happy to be without them. For just here, in this practical domain, our freedom, our vaunted abundance, takes on the sinister (to me) appearance of compulsion and scarcity. And I resist. You would be surprised (unless you too have resisted) to find out how hard it is. The word processor, for example. People, young and old, keep trying to convert me to using a word processor; it is for my own good, they tell me. I will see if I only try. It is like being surrounded by a religious movement, calling on me to join them and be saved. The pressure becomes wearisome, always the same arguments, and finally they start coming from one’s own family—a treacherous breach of my defenses. Some morning—Christmas or a birthday—I will find the egregious word processor tied up in pink ribbons in its hood on my desk. Even if I am spared that (“My dear, how can I thank you?”), I will lose the battle, if I live long enough, by simple force of attrition. It will be impossible to buy a new manual typewriter of the kind I like. Already my last two have had to be second-hand. And how long will workmen repair old manual typewriters? When I called the typewriter man last September to fix my three old Hermes machines—a Baby, a Rocket, and a big desk portable—his wife said he would be at the junior high school all week putting their word processors in shape. No time any more for my job. Let us not talk of micro-film replacing books in libraries. If I tell you that it is possible to rent a car without a credit card, you will doubt me. But it is true—you can—but even to tell about it is like recounting some long, complicated history of medieval adventures.

The element of compulsion, of harsh necessity, coiled in the innards of our contemporary freedom is most evident when action is involved, even such a simple action as purchasing a typewriter, renting a car, casting your ballot in an election for a candidate of your choice. Attempting such actions, you find you are bucking a tide. Like somebody trying to get out of a crowded subway car when everyone else is trying to get in.

Performing such actions, during which a considerable part of our lives is spent, we may chance to discover, if we run afoul of the machinery, that it is an apparent freedom we have been enjoying. A freedom that, on the whole, we have ascribed to scientific progress as it has liberated us from onerous necessity. Thus the equation of science with freedom on the one hand and with progress on the other has been, as I said, pretty much taken for granted in the West. Freedom is recognized as useful, very good for science if for nothing else.

This is true, evidently. Yet it is true, I think, of a special kind of freedom, a funny kind of freedom, which is tied to the processes of discovery and invention. Here it is obvious that freedom of inquiry is useful in facilitating exchanges of data and information, in a sort of pooling, in other words, for human knowledge seen as a group undertaking. The utility of this kind of freedom has a kinship with what the 18th century called “free thinking.” As defined by Webster, a freethinker is “one that forms opinions on the basis of reason independently of authority.” And, “esp. one who doubts or denies religious dogma.” As dogma can be an obstacle barring the way to scientific conclusion (e.g., that man is descended from an ancestor he shares with monkeys, or that the sun turns around the earth), so free thinking, immoral or not, is clearly the adjunct of scientific discovery. Hence, I repeat, it is good for something, from the manufacture of vacuum cleaners to the theory of relativity, with its chain of consequences, which in retrospect are seen as necessary, that is, by no means free.

Now, the freedom I am going to propose to you is the opposite of all that. What I have called in the title “Useless Freedom.” It is not good for anything; it exists of itself and for itself. Having no products, it cannot even bring happiness, though a brush with it, a brief flashing vision of it, can give a sense of joy or splendor, such as in Wordsworth’s “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,” referring to the French Revolution, of which it could be said that no good came of it in the immediate and not much in the long run. This pure and useless freedom may be an intimation of immorality, a touch of the eternal. It is an ideal quality like beauty or justice, which we can never see incarnate in a wholly just act but which we recognize through knowledge of its opposite—injustice—and through bits and pieces of itself. We know it without having wholly possessed it.

To know freedom, to sense its presence, is probably not a group experience. It is something one senses most keenly when alone, in a room in the woods. Tolstoy, in the last chapters of War and Peace, when trying to analyze the queer relation between free will and necessity (which is the whole subject of his book), concludes that man’s will is most free when he is alone in a room relieved of constraints imposed by the mere presence of others, and the freedom his will has in that circumstance is limited to the power to decide whether to raise his arm or not.

A derisory sort of freedom, you could say, not worth having, not good for anything but the simplest acts. But this freedom, in my view, is the ultimate value, like beauty, which we know without possessing. It is the same as being alive, which simple is, of and for itself. For this reason I would count freedom as the very highest value, since it does not serve anything, no ulterior end, no purpose. We should live with it to the limit of our possibility, never relinquish it voluntarily as the result of some sort of bargaining, interior or social. We must not let ourselves be intimidated by the dangers, real and imaginary, freedom presents; if liberty says anything, it says “Live dangerously.” I am sure that if you examine freedom, somewhere near it or woven into it, strand by strand, you will find courage.