On February 4, 2024, during a memorial paddle-out at Zuma Beach for Malibu surfer Lyon Herron, Matt Rapf left us dramatically and unexpectedly. If nothing else, my old friend did nothing in half measures. Quick to the trigger when it came to Standup Paddleboarders and entitled plutocrats who surf, Matt led with his chin (backed up by a big right hand) and always wore his oversized heart on his sleeve. A man of great passion with a voracious appetite for life, Matthew Rapf, Jr. was a husband, father, writer, fighter, surfer and finally, a good shepherd who helped and inspired many to face their demons the same way that he had faced his.

Initially, my relationship with Rapf was transactional and adversarial. When he called me “MaSquire” or “P.T. Barnum,” it immediately transported me back to Malibu Colony circa 1970. My next door neighbor, Ian Warner, a hard nut even at six, brokered our first meeting in the street behind our houses. I suspect that we met in the street because Ian’s mom, Miki Warner, would not have approved of the big, brash seven-year-old taking advantage of her favorite five-year-old.

The Ma Barker of our Colony surfing tribe, Miki had known Matt since he was three, and even then he “sensed she saw me as a pathological, lying, spoiled, dangerous, stealing, bullying, corrupting, unrepentant, accident-prone pyromaniac,” wrote Rapf in his soon to be published novel, Tres Fiestas. “Other than that, I could not figure out what her beef was. I was just a kid growing up having fun.”

We were there to negotiate the terms of a trade and Rapf was all business—my big, plastic Red Baron triplane for his battered Corgi James Bond Car (sans ejection seat victim and working rear window bullet shield). Although I had misgivings, my motives were not pure. Ian had told me about the Rapfs’ pinball machine, pantry full of sugar-coated cereal, and his parents’ laissez faire attitude towards their youngest son’s discipline. I wanted in on the fun.

By seven, Matt Rapf was already a legend of excess in the Colony, “Mom brings me seven boxes of cereal home from the market so I can get all the prizes inside,” he wrote. “Mom knows how much I love the prizes.”

Worse than not getting to play pinball, or partake in the cereal orgies, a day later, I saw my red triplane in the hands of another Colony kid. Matt had traded it to him for something much better than his old, battered James Bond car. Even at five, I knew that I got played.

Matt Rapf was to the Hollywood manor born. His grandfather, Harry Rapf, was sometimes referred to as “the fifth Warner brother.” The son of an Austro-Hungarian tailor was born in New York City in 1881. Harry got his start in Vaudeville before migrating to Los Angeles in 1921 to work for Warner Brothers. After Rapf produced canine star Rin Tin Tin’s first film, Where the North Begins, many credited him with saving the studio from bankruptcy.

In 1924, Harry Rapf accepted an offer from Louis B. Mayer to work as a producer at his start-up, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios. There, he was “responsible for more than half of the movies produced by MGM during its first few years of operations in the silent era,” wrote his screenwriter son Maurice in his memoir Back Lot: Growing Up With the Movies. “One can’t really talk sensibly about Hollywood and how it flourished without talking about the Jews who crossed the continent to be its pioneers and were to sit on the thrones of its major companies for the next forty years,” he wrote. “I feel qualified to write on this subject since my father, Harry Rapf, was one of those pioneers.”

In addition to being to the Hollywood manor born, Matt Rapf was also to the Malibu manor born. Harry Rapf liked to fish, so in 1929, he built a large weekend house for his family at May Rindge’s ultra exclusive “Malibu Movie Colony.”

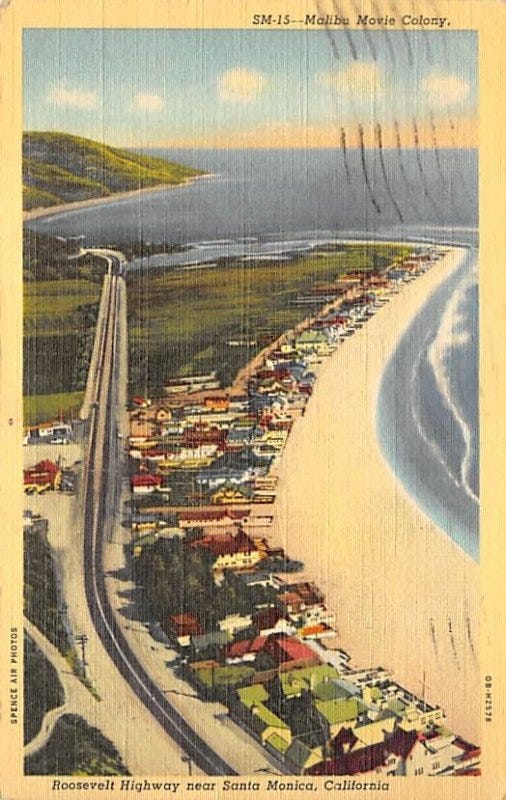

Financially drained from her legal battles against the ever-encroaching state of California, Rindge, the original territorial Malibu local, began leasing 30’ wide lots on a one-mile stretch of beach of her 13,000 acre ranch in the late 1920s.

Although “The Queen of Malibu’s” private infantry and cavalry had kept the invaders out since the late 1880s, the fight had now moved to the courtroom, and the end of her Rancho Malibu was near. With a private entrance and armed guards, “The Malibu Movie Colony” quickly filled up with the silent film era’s A-listers. Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Gloria Swanson, Clara Bow, Delores Del Rio, Myrna Loy, Barbara Stanwyck, Joan Crawford (who was discovered as a 16-year-old dancer by Harry Rapf), and too many others to list owned beachfront bungalows in the private community.

On Saturdays during the summer, Harry Rapf and his Hollywood friends usually chartered a fishing boat at the Malibu Pier, then combed Santa Monica Bay for yellowtail, halibut, calico bass, and barracuda. Afterwards, his sons Maurice and Matt cleaned the fish, then distributed some of the catch to favored Colony neighbors like Frank Capra, Herbert Brenon and Margaret O’Sullivan. “Our rewards might be delicious milk shakes at the Brenon’s living room soda fountain or a sail with O’Sullivan’s boyfriend, and later husband, John Farrow,” wrote Maurice Rapf.

On Sundays, the Rapf’s beach house was open to both invited guests like the Schulbergs and the uninvited who had heard about Grandma Rapf’s legendary pot roast (made with brisket), potato pancakes, and other old world delicacies. “It was fun,” wrote the elder Rapf brother. “Some of the happiest years of my life were spent in Malibu.”

By the 1930s, the bohemian, beach lifestyle that has come to be associated with Malibu was well established. Although the tee totaling May Rindge included a provision in her tenants’ leases that they “must not consume liquor,” even during Prohibition the Colony never ran dry. Legendary rum-runner Tony “The Hat” Cornero delivered their booze by sea.

Douglas Fairbanks was said to swim naked, Gloria Swanson practiced vegetarianism and yoga, and Hawaiian waterman extraordinaire Duke Kahanamoku taught Academy Award-winning actor Ronald Coleman and actresses Clara Bow and Myrna Loy how to surf.

From its inception until today, there has always been political activity in the Colony. An active member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), Maurice Rapf held beach parties at his parents’ house to recruit new members. “The beach was certainly a fertile recruiting ground…,” wrote Rapf. “As an astute member of the Party said several years later that one of the reasons for the success of recruiting in Hollywood was the Party’s reputation for attracting the prettiest women in town.”

When May Rindge was finally forced to sell the Malibu Movie Colony in the late 1930s, more and more celebrities bought property and began to build larger, more permanent beach houses. By the 1950s, Bing Crosby, Jack Warner, and many others owned houses in one of the world’s most exclusive gated communities. After Matt Rapf, Sr. bought his first house in 1958, he and his second wife Carol, and their sons (from previous marriages) moved in and lived there full time.

A gruff, no-nonsense man, “Mr. Rapf” as I knew him, graduated from Dartmouth in 1942, then immediately enlisted in the military and served as a Navy lieutenant in World War II.

In 1946, just as Matt, Sr. was returning to civilian life and starting his career as a screenwriter, Hollywood Reporter founder William Wilkerson published a column entitled, “A Vote For Joe Stalin.” In it, he named Maurice Rapf, Dalton Trumbo, Ring Lardner, Jr. and eight others as Communist sympathizers. The names on “Billy's Blacklist” formed the core of what came to be known as “The Hollywood Blacklist.” While Rapf did not have to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) “due to an illness,” his official career in Hollywood was over.

Initially, Harry Rapf was frustrated by his rebellious son, but after he was blacklisted, the Rapf family closed ranks. “My brother Matthew was even more loyal to his renegade relative than my father was,” wrote Maurice. “He not only defended me openly, but refused to hire anyone who had turned fink and ‘named names’ during the Red hysteria of the HUAC.” Although he continued to work in Hollywood under pseudonyms, the elder Rapf brother eventually resettled on the East Coast where he worked as a film critic, then a film professor at his alma mater Dartmouth.

Matt Rapf, Sr. followed in his father’s footsteps and embarked on what would be a successful career as a film and television producer (best known for The Loretta Young Show, Ben Casey, and Kojack). Even when he was not working in the Colony, “Mr. Rapf,” was always conservatively dressed in “slacks,” loafers, and expensive collared shirts. Like his father, Matt, Sr. fished, played a tenacious game of tennis (always a force to be reckoned with in Colony tennis tournaments) and enjoyed a sundown Scotch and soda.

Matt, Sr.’s second wife, Carol Tannenbaum, was the daughter of powerful lawyer and two-term Beverly Hills mayor, David Tannenbaum. After working as an interior decorator and restaurateur, she would take the high-end Malibu real estate game by storm. Camouflaged in immaculate tennis whites and armed with an easy smile, Carol Rapf’s daily Colony bicycle reconnaissance patrols would have impressed even legendary OSS and CIA operative Virginia Hall.

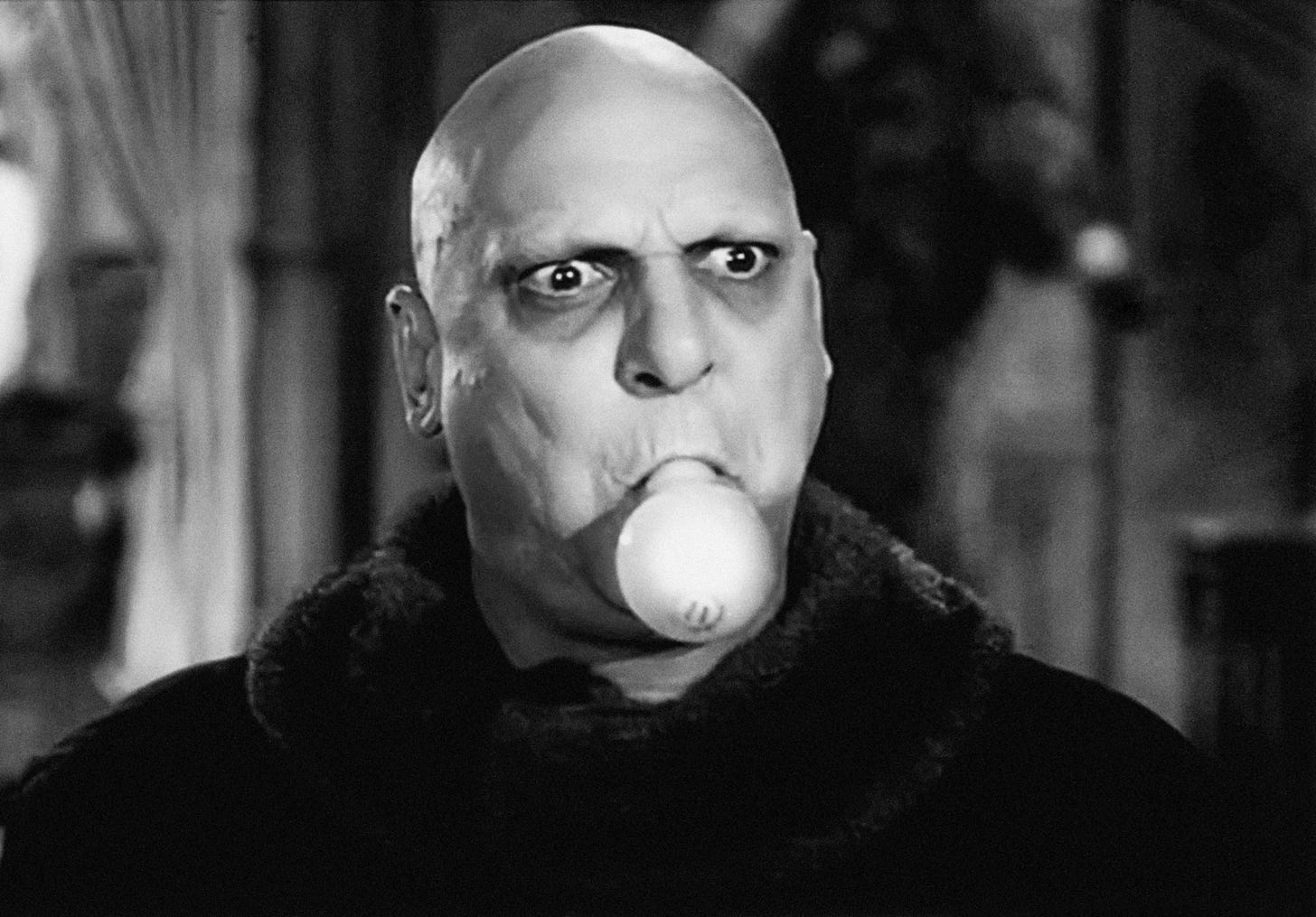

Born in 1962, Mathew Rapf, Jr. was his parents’ only biological child and Carol’s greatest indulgence. “She’d love me if I was a serial killer, ‘But your honor, he’s so good with his hands, and look at his eyes. They’re hazel,’” Rapf wrote.

As soon as the Rapfs moved to the Colony, their sons began surfing. Their private beach had a right called “Little Beach” or “Colony” at the north end and “Old Joe’s” reef (named after Joe Schecter) at the south end that produced excellent lefts in south swells. The Colony also had a rich surfing history. Child star Jackie Coogan, lawyer Joe Schecter, legendary test pilot Bill Bridgeman, and early action movie star Richard Jaeckel all surfed in the Colony.

Other early Colony surfers included Terry, Myles, Kevin, and Ann Connolly, the children of producer and screenwriter Miles Connolly. In addition to his house at “Old Joe’s,” he also owned “Connolly’s Hill,” the property that overlooks Malibu’s Surfrider Beach.

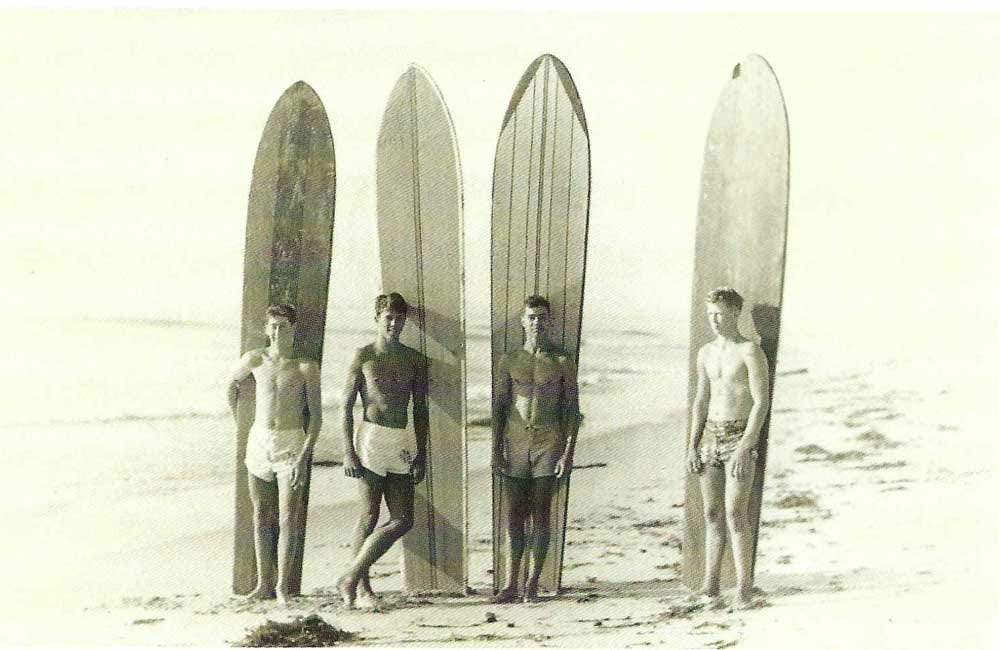

During the 1950s, Terry Connolly, Mort Gerson, Hobbs Marlow, Joe Dunn, George Elkins, Jr. and Tim “Glider” Lyon regularly surfed the Colony, Point Dume and Malibu.

While many of the Colony surfers were content surfing private waves, the gaptoothed “Glider,” was a Malibu pit regular and part of the first generation of “Coast Haoles” to travel to Hawaii to surf in the early 1950s.

By the 1960s, surfboards were as common in the Colony as Schwinn Stingrays. The Colony had their own lifeguards, an underground surf club called “The Colony Cool Cats,” and resident Butch Linden and Johnny Fain (lived on “The Old Road”) were among the best at Malibu Point.

Colony community spirit was bolstered by 4th of July and Labor Day parties, tennis tournaments, luaus, and an extremely competitive annual surf contest.

By the time my family moved into our house at the foot of “Old Joes,” the Colony surfing tribe was led by the sons of pioneer California watermen like former Santa Monica lifeguard and early Malibu surfer Ralph Kiewitt, early “Coast Haole” Hawaiian surfers George Elkins, Jr. and Tim Lyon. All three owned homes in the Colony and lived there full time. Their sons, John Kiewitt, Timmy Elkins, and Steve Lyon were some of the older surfers I looked up to most.

Other Colony standouts included surfer/shaper Trey Elkins, Bob Feigel, Pete Chamois, Freddie Roberts, Marty Sugarman, Tommy Longo, the Horner brothers (Willie, Tommy, Bobby and Bingo), the Lyon brothers (Steve, Andy, and Matt), the Roberts brothers (John and Mikey), the Warner brothers (Matt and Ian), and the Beck brothers (Curtis and Marcus). They set a very high bar for the Colony surfers during the 1970s. Other Colony surfers included: Brian Asher, David Kaufman, Tommy Nathanson, David Gerson, David “Bugsy” Seigel, Gavin Grazer, the Marin brothers (Alden and Brit), and the Palmieri brothers (Hank and Matt).

“Colony Cool Cats: 1973,” wrote Colony lifeguard and our surfing elder, John Kiewitt. “These kids had hung around us older guys and wanted to make their own mark. They were real bratty, a radical crew, mostly from monied families, they didn’t demonstrate a whole lot of restraint. I knew that one day they’d all grow up and move away. Some would become lawyers and some substance abusers.”

If Kiewitt thought the Colony Cool Cats of 1973 were radical and had shown no restraint, the hot crop of Colony gremmies [young surfers]—Ian Warner, Andy Lyon, Matt Rapf, Nathan Baker, Matt Lyon, Andy Barton, Drew Luster, Charles and Cameron Helfrich, Will Kargus and others —would leave their marks, both in and out of the water, during the 1980s.

Matt Rapf began surfing in grade school. He begrudgingly took tennis lessons and played little league, but deep down he hated team sports and only wanted to surf. Unlike his neighbors and oldest surfing buddies Ian Warner and Andy Lyon, Matt was not a natural surfer. In fact, he was somewhat clumsy, extremely accident prone, and had a very dangerous relationship with fireworks (really all things fire related). Nonetheless, Rapf made up for what he lacked in natural talent with hard work, dedication, and time in the water.

To Matt Rapf, surfing was about more than just riding waves, it was about being part of an elite subculture. “As a young kid, the Colony Lifeguards were royalty. They sat at their posts in red trunks with the Colony lifeguard patch surveying the beach and were amazing watermen,” Rapf wrote. “They always had hot girlfriends and I loved to sit in the sand next to their stands and listen to tales of big swells, mythical surf figures and crazy luaus. Everyone who walked by the beach saluted them.”

Although Malibu’s Surfrider Beach was only one hundred yards from Matt Rapf’s bedroom window, it was a world away. Many of the Colony’s dilettante surfers avoided Third Point like the plague, but the best surfers were drawn to the meritocratic proving ground.

Unlike the Colony breaks, Malibu’s brutal hierarchy was ruled by the big, bear-like men Matt Rapf referred to as “The Beards.” At Malibu you were only judged by what you did in the water, not your parents’ wealth or the size of your house. Over time, through trial and error, Rapf realized that if he surfed Malibu regularly and made his waves without falling, “the beards will give you begrudging respect.”

By 1974, twelve-year-old Matt Rapf was surfing Third Point almost every day. For him, catching a set wave was unlike anything he had ever known. “I am aware that each time I launched down the line on the swells, I am doing something rare that most of the planet will never experience,” Rapf wrote. “When I kick out down the line and I get a few hoots, I experience the greatest feeling I have ever known.”

There was only one problem with Matt Rapf, Jr.’s obsession with surfing. The man he looked up to most, Matt Sr., “did not consider surfing the sport of kings, but a hobby of the heathen.” His father soured on surfing after his oldest son Jim began surfing Malibu in the 1960s. There, he befriended a giant Hawaiian named “Moki” who lived on the beach during the summers. When the Hawaiian joined the Rapfs for a family dinner in the Colony, Matt, Sr. asked him what he planned to do with his life. Moki told the now successful producer that he was saving his money to attend UCLA. Impressed by the young man’s ambition, Mr. Rapf, a good Hollywood liberal with a soft spot for underdogs, wrote him a check for the balance of his tuition. “The next day Moki cashed the check and went back to Oahu never to be seen again. That was my dad’s first impression of surfers and it hasn’t improved since,” wrote Matt Rapf, Jr. “Dad could never get behind my surfing. He believed surfers were derelicts.”

After my parents divorced, I moved from the Colony to Pacific Palisades and did not see Matt Rapf, Jr. again until I was fifteen. I learned how to bodysurf and surf at State Beach’s Tower 18, my father’s house at Santa Claus Lane and my grandfather’s house at Rincon Point.

The next time I saw Matt Rapf was on a sunny, glassy weekday afternoon at Rincon. When a big-boned guy paddled past me I noticed him because his red, white and blue Natural Progression Pro Series looked identical to one that I owned but was not riding that day.

I looked at the board’s owner and said with a smile, “I have a Pro Series exactly like that!” As Matt Rapf spun to catch a wave, he scowled at me and said, “I snuck into your yard and stole it!” What a dick! I thought to myself as he vanished down the line.

Beautiful older sisters can open a lot of doors. After Colony resident Monica Fulton (Ann Connolly’s daughter) introduced my older sister Robin to our old neighbor Matt “Chief” Warner, they fell in love.

The Gerry Lopez of Old Joe’s, Chief was an elegant goofyfoot with a kind heart. Not only did he sense my misery, we shared common foes, my dad and stepmother. They did not approve of Robin and Matt’s relationship. During the summer of 1980, Matt Warner began taking me to the Colony to surf Old Joe’s. By now the Warners and the Rapfs owned the last two houses in the south end of the Colony. It was there that I reconnected with my childhood friend, Ian Warner (Matt’s younger brother).

Ian Warner was the best Colony surfer of our generation. After a good showing in the Malibu Sunkist U.S. Pro, he was about to embark on the International Professional Surfing circuit as the only Californian on the prestigious Town and Country surf team. “He [Ian] looked like a mixture of John Belushi and Tarzan. He was the best surfer I’d ever seen, a natural,” wrote Rapf. “He’d fly past all the new wave wetsuits at Mach Ten with his low center of gravity, spraying the invaders for good measure as he set his sights on Second Point. I looked back and saw him crack a ferocious off the lip and bellow to the cattle: ‘Look out you goons!’”

At roughly the same time, I was reintroduced to Matt Rapf. He was not as friendly as Ian and looked at me dismissively, probably thinking another goyim volleyball player who surfs. Then, he pulled out a big joint of Thai, lit it with an Ohio Blue Tip match, took a hit and looked me in the eye as he passed it to me. After we smoked it down to the oily roach, he realized that impressions can be deceiving. “Peter from the Palisades,” wrote Rapf. “He’d been coming to the Colony for decades and was quite crafty. He was smart as a whip, looked like an east coast blue blood, but he could smoke Cheech and Chong under the table.”

Matt Rapf, Jr. and I shared more than surfing and pot. We both also loved to fish. Like his grandfather and father before him, he fished for the calico bass and halibut that lurked just outside the surf line. Instead of a chartered boat like the one Harry Rapf had waiting for him at the Malibu Pier, his grandson had a small, outboard-powered aluminum skiff that he launched through the surf.

When Matt invited me to join him on a late afternoon fishing expedition, I jumped at the opportunity. I made sure that we were well-provisioned with root beer-colored Scampi lures, Thai joints, and cold Coors “Banquet Beer.” It was during these fishing trips that I got to experience Matt Rapf’s razor-sharp wit and a brutal self-deprecating sense of humor. It was as if Woody Allen had a gnarly cousin who surfed, did not suffer fools, and was his own harshest critic. “At my low points, I looked in the mirror and saw Woody Allen. During moments of triumph,” Rapf wrote. “I saw a resemblance to Sean Penn, with a slightly larger forehead and uncomfortable thoughts making his eyes twitch. In reality, with the Hebrew heritage of a shark fin for a nose, I was closer to Dustin Hoffman, with a merciful and generous concession of blonde hair, but who knew how long that would last.”

In the boat, I needled Rapf about his Malibu Colony limousine liberalism. He countered with well-placed jabs about my Westside Manchu WASP roots and my family’s membership to equally insular, antisemitic, anti-black and anti-Hollywood beach and country clubs. Rapf did not know that my great-grandfather had been a judge at Nuremberg or that Israel’s first Prime Minister David Ben Gurion had called my grandfather “The Irish Moses” for flying at least 40,000 Jews into the fledgling state of Israel. I did not know that Matt’s uncle Maurice had been blacklisted or that his dad had served in World War II.

The brutal, no-holds-barred banter that began in that aluminum boat continued whenever we were together. While we genuinely liked each other, our relationship remained competitive and transactional. Rapf surfed better than me, but I had a much larger social network. Not only were my manners and social skills more polished than his, I knew the shiksas in Dolphin shorts that he longed for.

When Matt Rapf decided to transfer from UCLA to UCSB, we struck a deal that was much better than the one I made with him in 1970. In exchange for my card key to the gate at Rincon and unlimited parking at “The Irish Moses’s” house at the Indicator, I got a coveted slot as a Malibu Colony lifeguard.

My life would never be the same.

To be continued…