Nate Thayer (1960-2023) - Part One

The Rise and Fall of a Gonzo Journalist.

Note to Readers: If you are reading this in your gmail account and you receive a “message clipped” notice, you can read the full post on the Sour Milk website. Gmail truncates emails that are larger than 102KB.

Nate Thayer died on January 3, 2023, at the age of 62 in Falmouth, Massachusetts. At the height of his powers, the tobacco-chewing yankee was the most fearless, independent journalist I have ever met. War crimes investigator Craig Etcheson put it best, “Nate Thayer was a gonzo journalist of the first order, the real thing, willing to embed with murderous genocidists for months on end in his search for the truth. His likes shall not soon pass this way again.” When it came to breaking stories during the civil war that simmered in the kingdom of Cambodia throughout the 1990s, he was in a league of his own. However, as award-winning Australian journalist, Mark Dodd, who served as Reuters bureau chief in Cambodia (1991-1995), pointed out in a heartfelt and brutally frank obituary about his old friend, “any honest appraisal of Nate has to look at the complete person. It’s what he would want.”

Nate Thayer’s father, Harry Elstner Talbott Thayer, was the scion of a prominent Philadelphia Main Line family. The Mandarin-speaking Yale graduate served in the U.S. State Department for thirty years and was an East Asian specialist. Deputy Political Counselor to the U.S. Mission to the UN at the end of Mao’s Cultural Revolution and Deputy Chief of Mission to the American Liaison in Beijing under Ambassador George H. W. Bush, Thayer was appointed U.S. Ambassador to Singapore in 1980. Because he was posted to Hong Kong, Taiwan, Beijing and Singapore, his son, Nate, spent a great deal of his youth in Asia.

Nate Thayer first traveled to the Thai-Cambodia border in the early 1980s to interview refugees and document Khmer Rouge atrocities. After the three-year, eight-month, and twenty-day experiment in Stone Age communism (1975-1979) that cost Cambodia close to two million lives, Nguyen Vo Giap, Vietnam’s greatest general, led fourteen divisions supported by planes, tanks, and troops into Cambodia. Not only did Vietnam stop the genocide, but they now occupied the nation. By the end of January 1979, Pol Pot and hundreds of thousands of his Khmer Rouge followers lived in camps along the Thailand–Cambodia border.

After his stint in Thailand, Nate Thayer returned to Boston, attended the University of Massachusetts, worked in a hotel, and at the Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority. In 1988, Thayer decided to move to Thailand to cover the intensifying fighting along the Thai-Cambodia border as a freelance journalist.

“A few months ago, George Jones was a desk jockey in an eastern state bureaucracy with prospects of steady work, good pay, and engaged to be married,” Thayer wrote about himself in a 1989 Soldier of Fortune article entitled, “Cambodian Border Massacre: American Crosses the Line to Save Lives.” “Reconsidering, Jones pulled the pin, went to Southeast Asia with a camera and started covering myriad mini-wars as a freelance photojournalist.”

Based in the Thai border town of Aranyaprathet, Nate Thayer, a naturally curious people person, quickly made contacts and developed sources on both sides of the border where the United States, China, Thailand, Malaysia, and Singapore were providing military and nonmilitary aid to an anti-communist resistance “coalition” that now included the Khmer Rouge. General Giap best described America’s strange new alliance as “an arranged marriage” and added, “The couple share the same bed but they have different dreams.”

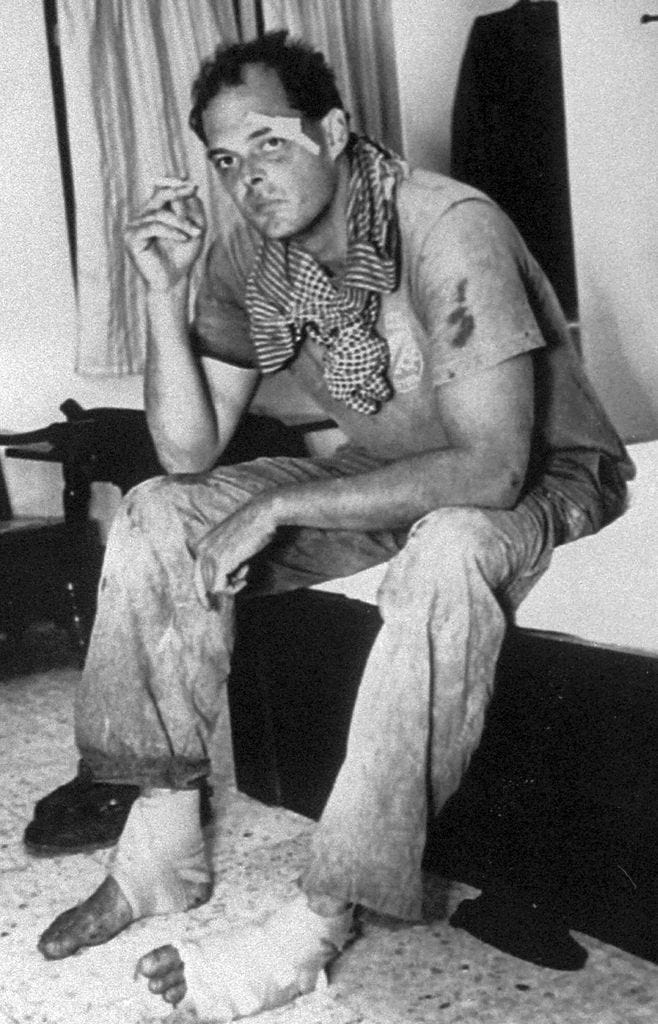

In October 1989, Thayer and Australian photojournalist Philip Blenkinsop got permission from the Thai military’s task force that controlled the border to join the anti-government forces on a mission across the border. He was in the front of a two- and-a-half-ton truck when they hit an anti-tank mine that instantly killed the soldiers sitting on either side of the American. “My eardrums were blown out. The concussion of the explosion was so great my brain shut down. I remember the liquid in my body became so heated I could feel it simmering near boiling,” wrote Thayer. “I could hear my blood boiling, gurgling from what seemed like heat. I felt my brain being tossed around like a rag doll bouncing off the insides of the wall of my boned skull.”

If anything, this brush with death emboldened him. After he recovered from his shrapnel injuries, Nate Thayer spent the next two years covering the fighting between the Cambodian government and the insurgents. In 1991, after UN Security Council members signed a fragile peace treaty that called for a massive UN occupation that would culminate with “free and fair” elections, Nate Thayer moved to Phnom Penh.

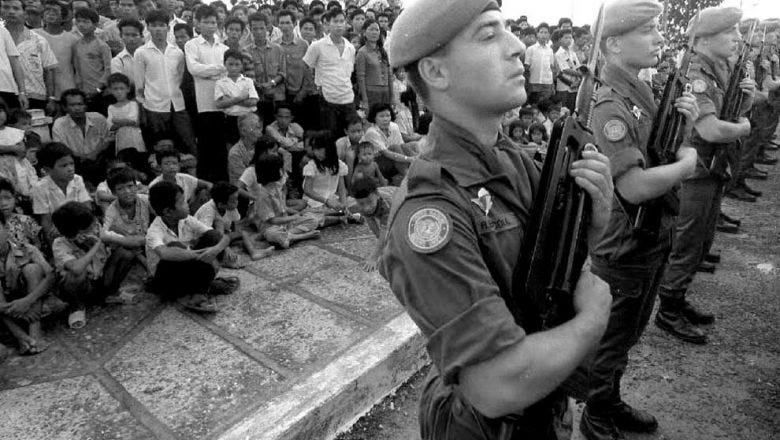

Between 1992 and 1993, the United Nations Transitional Authority Cambodia (UNTAC) imported 15,000 soldiers and 5,000 civilian advisors to Cambodia in a $3 billion effort to end twenty years of war and build democracy in a country that knew only oligarchy and dictatorship. Because UN workers received a daily per diem of $150, more than the annual income of many Cambodians, Phnom Penh transformed overnight into a boom town that attracted the good, the bad, and the ugly. In addition to the UN staffers and soldiers, NGOs representing every conceivable cause—refugees, mercenaries, triads, Vietnamese prostitutes, Le Milieu, Chinese gamblers, pedophiles, arms dealers, grifters, and the press—flocked to the kingdom’s capital.

Every bit as impressive as Associated Press, Reuters, and Agency France Press who had bureaus in Phnom Penh was a homegrown, English language paper called Phnom Penh Post. Founded in 1992 by the husband and wife team of Michael Hayes and Kathleen O’Keefe, who invested their life’s savings into the paper that operated out of a villa on Street 264, the Post was a thick, bi-monthly that pulled no punches. In addition to covering Cambodia’s breaking news and a stomach-turning “police blotter,” the paper featured excellent opinion pieces by subject matter experts that often spurred no-holds-barred debates that spilled over into the letters section.

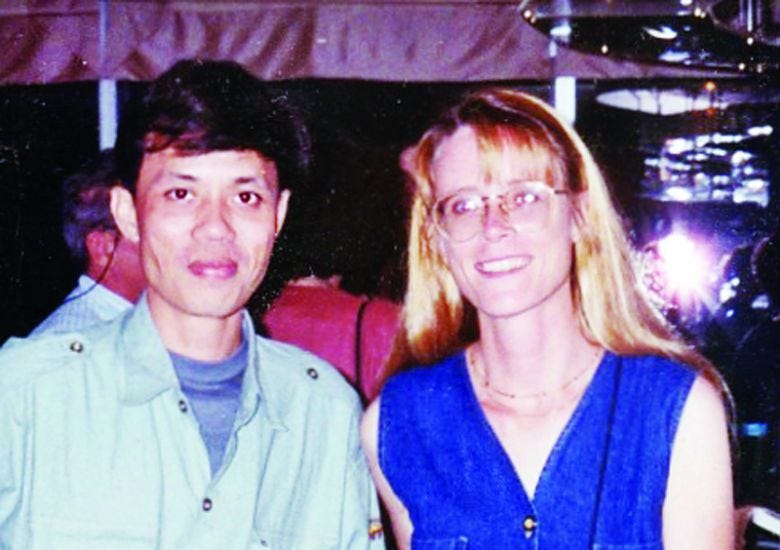

Under the watchful editorial eyes of Michael Hayes, Kathleen O’Keefe, and Sara Colm, Nate Thayer did some of his best work. During this time, Thayer wrote for both the Far Eastern Economic Review (FEER) and the Post. For four years, Thayer and Hayes lived together at the Post’s villa and had an “Odd Couple” relationship. “He was a total slob,” wrote Hayes. “I had to yell at him to stop spitting his tobacco chew juices in the ant traps under the legs of my coffee table.” Despite their stylistic differences, Michael Hayes and Nate Thayer made a formidable team.

“Nate was great to work with,” wrote Post Managing Editor Sara Colm. “Even though he already had a bit of a name he always treated me with respect and appreciated my edits of his stories. I remember him strolling around the newsroom of the Post in his fluffy white bathrobe, a plug of tobacco nestled in his cheek as he regaled us with tales of his latest scoops.”

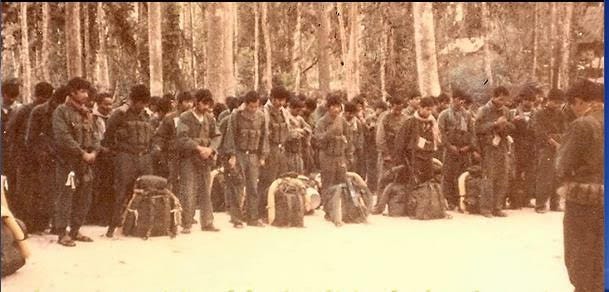

In 1992, Nate Thayer heard a rumor that members of FULRO (United Front for the Liberation of Oppressed Races), a Montagnard “Lost Army” that everyone assumed had been wiped out in the 1970s, were alive and living in the remote jungles of northeast Cambodia. Commonly and collectively referred to as “Montagnards,” one million highlanders from more than thirty distinct tribes once populated the highlands of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. America’s most valiant ally during the Vietnam War, the once formidable army began fighting the Vietnamese in 1964. Although the U.S. promised them an autonomous homeland and later American asylum, they were abandoned and faced a Vietnamese vae victis (woe to the conquered) instead. By the time the U.S. withdrew from Southeast Asia, 85% of their villages had been destroyed, and half of their adult males were dead, but they never surrendered.

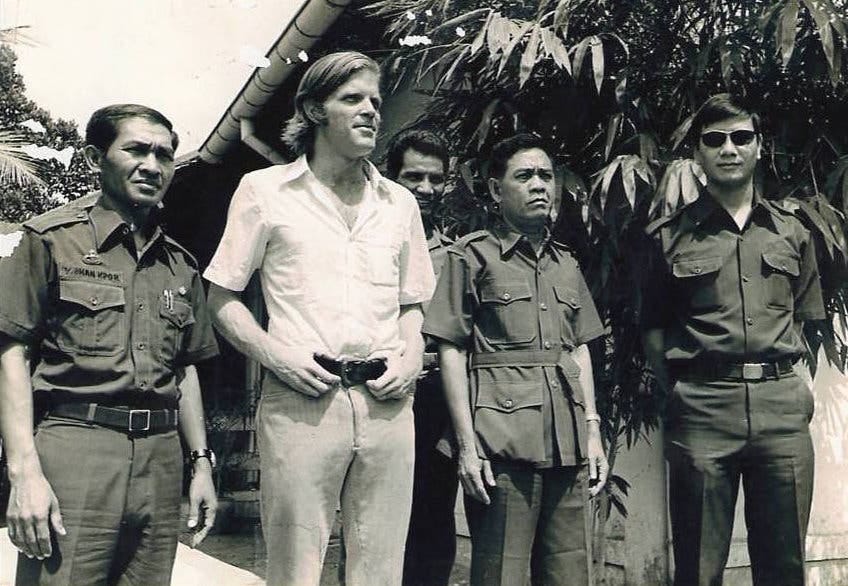

Thayer heard that a contingent of FULRO soldiers had recently emerged from the jungle on the Vietnamese border and asked a group of Uruguayan UNTAC soldiers stationed there for the arms the U.S. had promised 17 years earlier so they could continue fighting the Vietnamese. “UNTAC was dumbfounded, wondering ‘who the hell are these guys?” wrote Hayes. The reporter did some research and made some inquiries to Washington. Given how close the Montagnards were to U.S. Special Forces, in no time the Post’s fax machine “was spitting out dozens and dozens and dozens of pages from some sources in DC, mostly background on FULRO,” recalled Hayes (who also recalled that it cost the paper close to $10,000 in telephone bills because the disorganized Thayer failed to file his expenses with FEER).

Thayer and Hayes flew up to Steung Treng, a town on the Mekong River near Vietnam, where the Uruguayan UN troops were headquartered. “We cooled our heels for two or three days in town, while Nate went into UruBatt HQ and worked his way to meet the commander, chat and make the request to go in to meet the FULRO folks,” wrote Hayes. “At the time, UNTAC HQ was also sorting out what to do, and they sent a team up from Phnom Penh, that then flew by helicopter way over near the Vietnamese border.” The FULRO soldiers presented a problem for the UN. According to the terms of the peace accords, they were supposed to disarm all “foreign forces.”

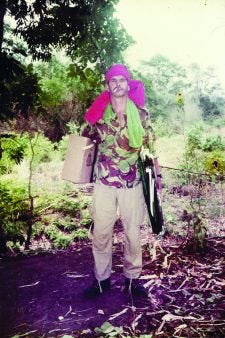

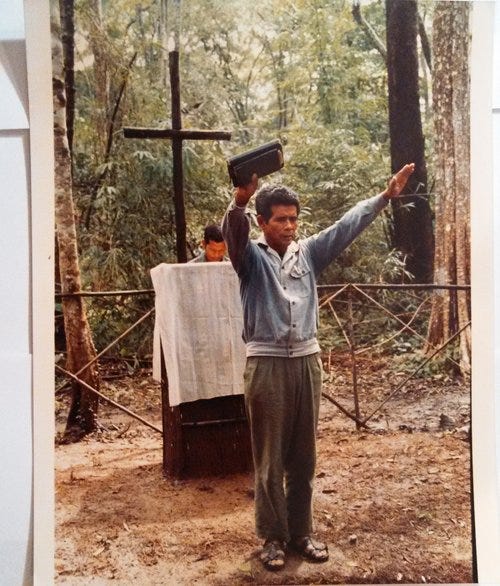

UNTAC brass granted the reporters permission to join their delegation on a visit to FULRO’s village, where they were going to meet their leaders and discuss the terms of their surrender. Thayer and Hayes boarded a Mi-17 helicopter, flew for three hours along the border, landed near where the Uruguayan soldiers had first encountered them and proceeded on foot until they reached the Montagnard camp. While the UN representatives negotiated the terms of surrender with FULRO leaders, Thayer and Hayes walked around and took photos of their bamboo church, huts, and other structures.

Although Hayes and the rest of the UN officials left a few hours later, Nate Thayer stayed behind in the village by himself for a week. He then caught another UN chopper out to file his story, “Lighting the Darkness”:

“MONDULKIRI - Accompanied by a chorus of crickets and the steady drumming of rain on the leaf roofs of their huts, scores of Montagnard fighters and their families gather in the jungle darkness each night to pray and sing. Lamps fueled by chunks of slow-burning tree resin give light to the few shared tattered bibles and hymnals as Christian songs of worship echo through the otherwise uninhabited forest. Familiar gospel hymns are sung in the tribal dialects of the mountains. For many at FULRO's scattered guerrilla bases, the ability to pray freely was a main motivation to flee their villages in Vietnam's central highlands 17 years ago.”

In the end, UNTAC convinced the FULRO soldiers to hand over their 194 old but perfectly maintained weapons, 2,567 rounds of ammunition, and a single M-79 grenade launcher (with one round), in exchange for safe passage to Phnom Penh and hopefully the United States.

The stories that FEER, Phnom Penh Post, and Reuters published raise awareness about America’s abandoned allies, and they led to the resettlement of more than 450 Montagnard fighters and their families to North Carolina as refugees. They were welcomed there by their old comrades from Special Forces, and the exodus of Montagnards to the U.S. continued for the next decade. Today, North Carolina has the largest Southeast Asian hill tribe population outside of Asia.

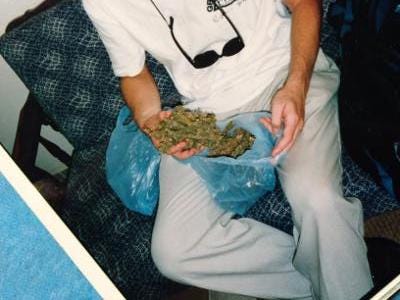

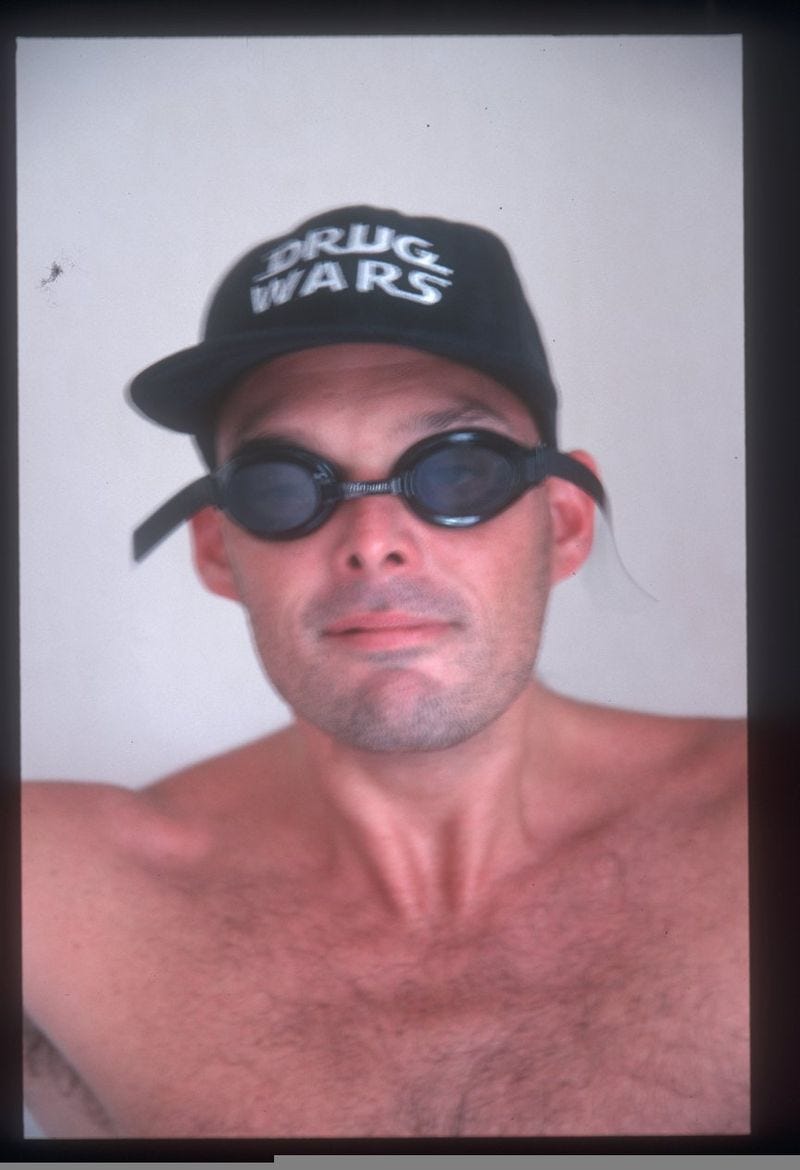

When he was not in the field, Nate Thayer could be found swimming endless laps at the International Youth Club and drinking at one of the boom town’s many raucous watering holes. Phnom Penh in the 90s was a place where every form of vice was on tap: $5-10 for a kilo of brown marijuana, $20 for a kilo of seedless green (if you could find it), $1 for a dozen Roche 10 mg Valium, $50 for a gram of pure China White heroin.

Although there were only 1500 prostitutes in the capital in 1990, two years later that number was up to 20,000. “As we dumped our gear on the floor, Thayer popped beers and said, ‘Welcome to the freest country in the world!’” wrote stunned Soldier of Fortune editor Robert K. Brown. “As if to reinforce his assertion, Thayer rolled and lit up a joint, continuing, ‘Anything you want. You can get a 50-kilo bale of pot at the market; there is an opium den down the street and you can pick up a case of AIDS without much difficulty.’”

Walking through Phnom Penh during the 1990s was an assault on the senses that made Times Square seem as serene as Bel Air. If you could cross the street without getting hit by a motorcycle carrying dozens of honking geese or by the cars speeding into oncoming traffic, there was still the gauntlet of the infirm that you passed on every street—one-legged soldiers, men with pincher-like arms, normal-sized heads, and torsos no bigger than basketballs, mothers with dying babies—each more horrifying than the last and all in your face, tugging at your sleeve and your conscience.

Because shoot-outs, and cowboy-style banditry were common in Phnom Penh, and because Thayer was regularly threatened by Cambodia’s violent political leaders, he occasionally carried a gun. Even the Soldier of Fortune editor was impressed by the large cabinet in the reporter’s room that contained “an old French MAT-49 sub gun, a selective-fire Chinese M-14, several AKs, an M-79 grenade launcher and cases of ammo.”

By the early 90s, the shaved-headed American cultivated and maintained a Kurtz-like persona among the western civilians who worked in the Cambodian press and the NGOs. “One night at the FCC in Phnom Penh, we were all sitting around enjoying a few cool ones, when Nate came in, lit to the gils, and started ranting and waving around his pistol,” wrote war crimes investigator Craig Etcheson. “He was loaded, and so was the weapon, so we were a bit alarmed. Without a word, Mark Dodd got up, effortlessly snatched the gun from him, ejected the mag, cleared the chamber, and slipped it back into Nate's hand. Nate appeared to notice none of this, not missing a beat in his rant, and we all went on to have a lovely night.”

Irrespective of his bravery in the field and occasional posturing and bravado, Nate Thayer could not count himself among the hard men—Légion étrangère, Aussie SAS, Union Corse, Chinese triads—who frequented Phnom Penh during the 90s. When Royal Air Cambodge lost the bag of Prime Minister Hun Sen’s powerful associate Theng Bunma, he expressed his dissatisfaction with the airline’s service by borrowing a pistol from one of his bodyguards, marching out onto the tarmac of Phnom Penh’s Pochentong Airport and shooting out the tires of the Boeing 737 he had just arrived on. “If they were my employees,” the tycoon told reporters when asked about the incident, “I would have shot them in the head.”

There was, however, one thing that Nate Thayer truly was: an impressive athlete with an iron constitution. “I was with him (along with Hayes and then wife Kathleen) one evening as we drank the Rock Hard Cafe dry,” wrote Mark Dodd. “We were off our tits yet early next morning Nate managed an epic swim across the…River beating the Cambodian Olympic swim team entrants - and take it from me, an ex pearl diver - that takes skill and fitness, which makes his final days even more sad.” Even more satisfying for Thayer, co-Prime Minister Norodom Ranariddh had to hang the medal around the neck of his sometime critic.

While the United Nations successfully repatriated 362,000 Cambodians living in Thai border camps and introduced modern ideas like party politics and human rights, the election in 1993 was marred by controversy. The incumbent prime minister, Hun Sen, refused to step down and was allowed to rule with the elected leader, Prince Norodom Rannariddh, as co-Prime Minister. Worse, the UN failed to disarm the Khmer Rouge and they remained a looming threat and throw weight in the civil war that would reach a full boil in 1997.

I first met Nate in early 1994 at the Foreign Correspondents Club. Overlooking the Tonle Sap and Mekong Rivers, the open-air, third-floor barroom was divided by rank. At the top of the natural elite, at least in my eyes, were Vietnam-era photographers like Al Rockoff and Roland Neveu, who had been working in Cambodia since the early 1970s. Thayer was about to embark on a two-week, elephant-back expedition along the Ho Chi Minh Trail in search of a rare Cambodian bovine. Still, he took the time to talk to me and I found him friendly, even courtly.

When it came to journalism, Nate Thayer was several steps ahead of his competition. In 1994, he helped negotiate the release of Cambodian Prince Norodom Chakrapong after he was accused of plotting a coup. Although co-Prime Minister Prince Norodom Ranariddh tried to expel him from the Kingdom, he returned. Never one to play favorites, Thayer also managed to get expelled by rival co-Prime Minister Hun Sen when he exposed his ties to heroin trafficker Theng Bunma. Expelled from the country or not, Nate Thayer always found a way to slip back in and break the biggest stories.

In 1997, Thayer accepted a visiting fellowship at Johns Hopkins Nitze School for Advanced Studies (SAIS) and took a year’s leave to complete a book on the Khmer Rouge. When he learned that Pol Pot’s defense minister, Son Sen, had been arrested as a traitor and executed, he knew that the Khmer Rouge was imploding and returned to the kingdom. Now, Nate’s many brushes with death, bouts of malaria, and time in the jungle were about to pay massive dividends.

The Khmer Rouge faction that appeared to be in control invited Thayer and his cameraman to their jungle readout. "It involved a very complicated and sophisticated underground network of Khmer Rouge covert operatives, who were ordered by their leadership to infiltrate me into the Khmer Rouge headquarters at Anlong Veng,” Thayer explained to journalist Dale Keiger. “It involved your traditional spy techniques of coded words and phone messages, and people in dark sunglasses and civilian clothes who picked you up and never talked and took you to hotel rooms, and then other people I didn't know came and knocked on the door and took me someplace else. It involved crossing international borders illegally."

I received a call from my colleague, Doug Niven, in Bangkok in late July, informing me that Nate Thayer and cameraman David McKaige had just returned from Anlong Veng with film of the ‘trial’ of Pol Pot.

I was happy for Nate and glad to see that a parachute journalist wasn’t going to steal the show from a reporter who’d paid such heavy dues for the story.

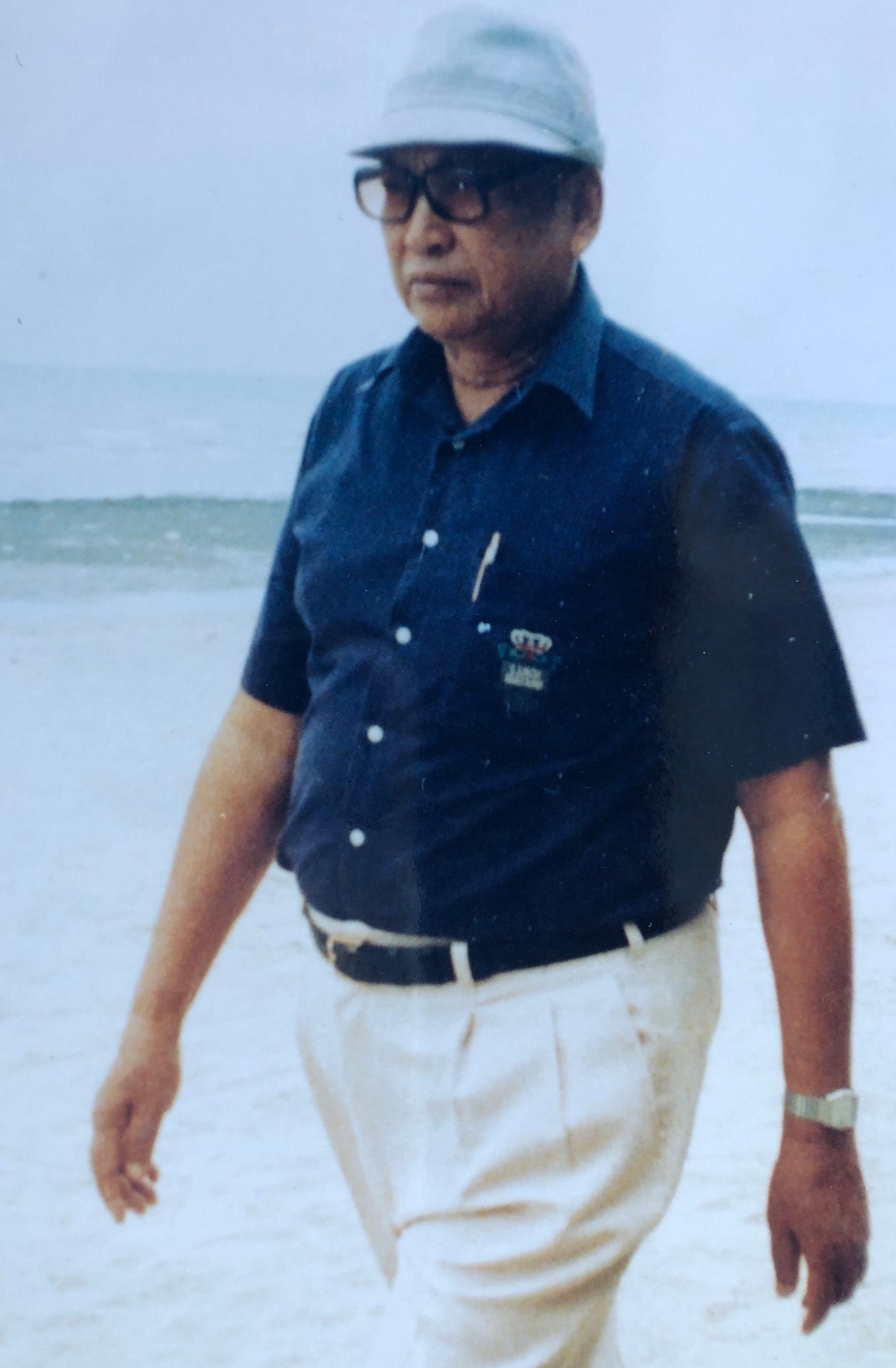

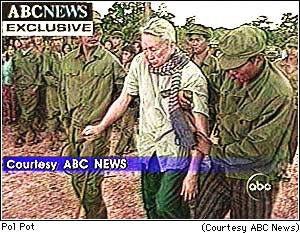

Thayer and McKaige arrived in Anlong Veng hoping to meet Pol Pot, but really did not know what was in store for them. "We certainly did not know that we were going to see a people's tribunal. All of a sudden, there we were with Pol Pot, with no warning, no notice, in what was probably the only trial, or pseudo-trial, we will ever see of one of the world's most notorious mass murderers," Thayer told Keiger. After two decades of intrigue and mystery, the elderly Pol Pot sat in a chair, looking old and pathetic, like the Wizard of Oz pulled rudely from behind his curtain. Brother Number One and three of his aides faced about one hundred of his most fanatical former supporters who pumped their fists and chanted in robotic, rehearsed unison: “Crush! Crush! Crush! Pol Pot and his clique!” The genocidal leader was sentenced to spend the rest of his life under house arrest.

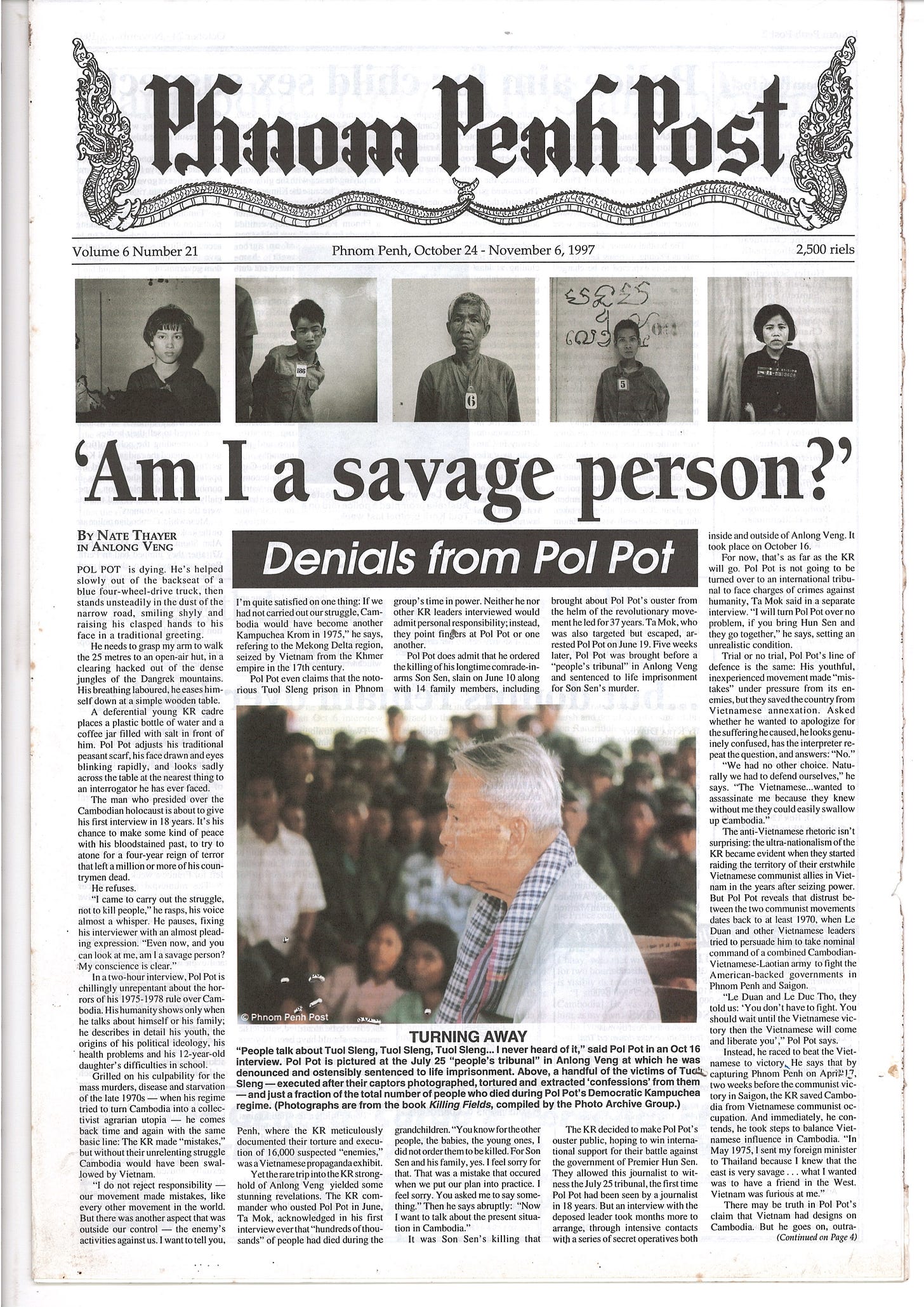

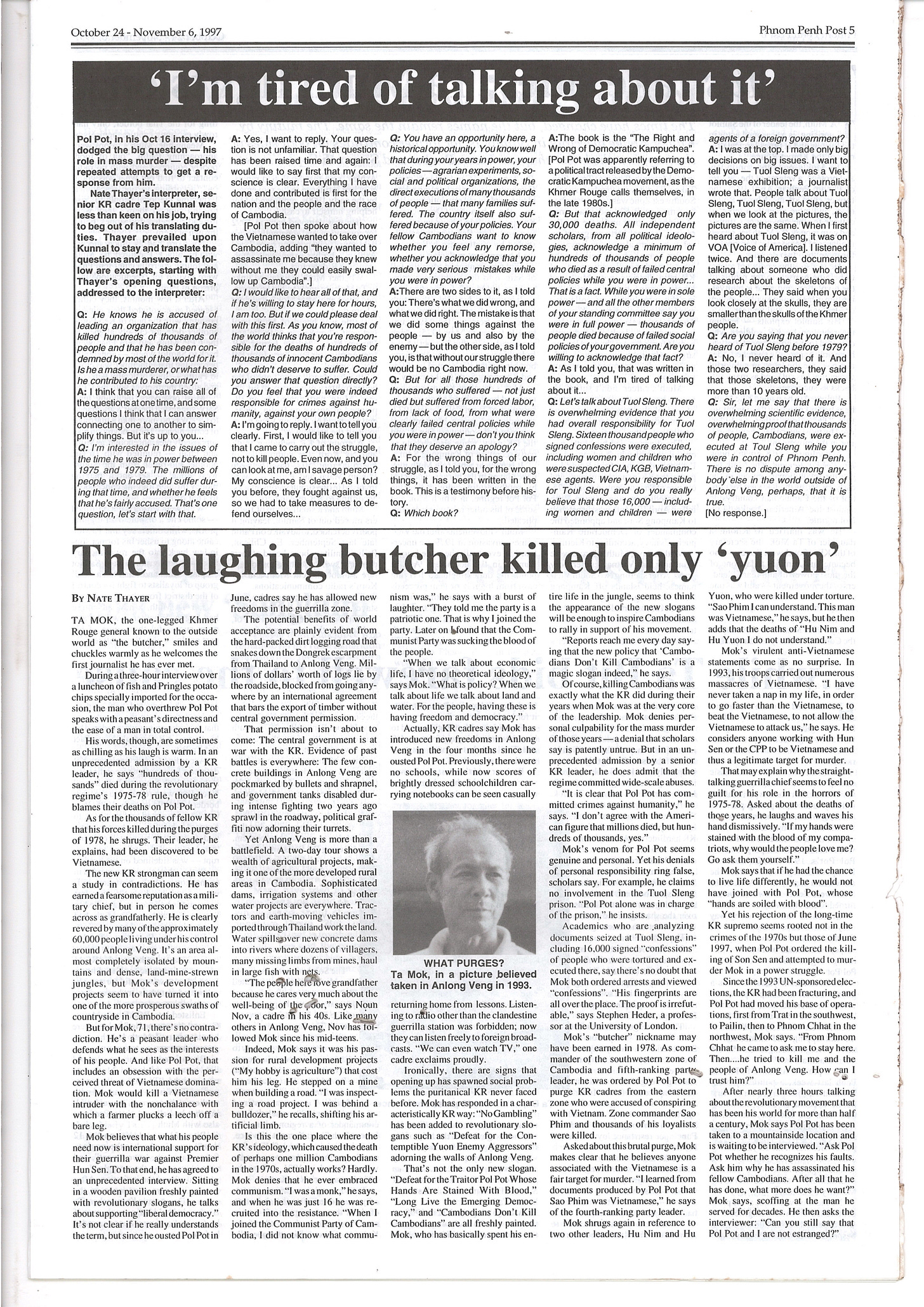

Nate Thayer was the first and only reporter to speak to Pol Pot while he was under arrest in Anlong Veng. Pol Pot told the reporter that his conscience was clear. When the reporter continued to press him, he denied everything, “First, I would like to tell you that I came to carry out a struggle, not to kill people. Even now, and you can look at me, am I a savage person?” Thayer asked if he felt any remorse for the “very serious mistakes you made while you were in power.” Pol Pot avoided the question and said only that the Khmer Rouge had prevented the Vietnamese from swallowing Cambodia, “I was at the top. I made only big decisions on big issues.”

For Nate Thayer, this was not only the scoop of a lifetime, it was the culmination of decades worth of work that left him forever scarred, both literally and figuratively. "Remember, I've lived in Cambodia. Most of my friends have had their lives destroyed by Pol Pot. So it was a profoundly moving moment. Here was a man who had destroyed the lives of millions of people, including most of the people I know,” Thayer told Keiger. “For them, I knew that what I was witnessing was an opportunity for closure. I cried many times for everybody I knew. It's not unlike if Hitler had escaped his bunker and was living in South America and was captured 20 years later, what that would have meant to Jews.”

When Nate Thayer returned to Bangkok, he was besieged by every major news organization on earth and offered huge sums for the exclusive rights to his footage. Thayer gave first rights to the The Far Eastern Economic Review for its standard fee. "This story was never about money or I would have sold to the highest bidder from the beginning,” he explained. “We wanted to do the story with integrity. That is why I chose to publish in the Review and go on Nightline."

Nate Thayer negotiated a deal with Ted Koppel and ABC. For $350,000 dollars, he granted them a one-week exclusive for the North American television rights only. The reporter believed that this would leave him with the world broadcast rights and valuable still photography rights. After all, a photograph of Pol Pot had not appeared in decades. Against the advice of his more media savvy colleagues, Thayer sent Nightline a copy of his tape of Pol Pot and the translated transcripts to his interviews.

Once in their possession, ABC pulled still frames from the video, placed ABC copyrights on them, distributed promotional stills and video far and wide, and made them available on their website.

The network also allowed a New York Times reporter to watch the footage. In the end, Nate Thayer’s story and photographs appeared on the front page of The New York Times and the rest of the world’s newspapers before his article ran in the The Far Eastern Economic Review.

Little did Nate Thayer, or really any of us, realize how quickly corporate ownership of the media and the internet was changing the world of journalism. Although Thayer thought that he had made a deal with Koppel “based on a hand shake and a man’s word of honor,” a spokeswoman for ABC held a different view. She told The New Yorker, “…this is what happens when you deal with a large news organization.” After Nate Thayer loudly, strenuously, and legally objected to Nightline’s conduct, ABC refused to pay him his $350,000 or speak to him.

Nine months later, Nate Thayer received a call from Ted Koppel, congratulating him for the Peabody Award “they” had just won. “‘Fuck you! Where’s my money?’” replied Thayer. “‘I’m going to the Peabody Awards. I am going to tell them what a fucking pimp ABC is and how you guys are thieves and an insult to the institution of journalism.’” Within twenty-four hours, the money ABC owed him landed in his bank account.

True to his word, Nate Thayer showed up at the Peabody Awards at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City, tapped Ted Koppel on the shoulder, and before security could escort him out, handed him a written statement: “Ted Koppel and Nightline literally stole my work, took credit for it, trivialized it, refused to pay me, and then attempted to bully and extort me when I complained. They should not be rewarded for this kind of behavior and I under no circumstances want my name associated with these egregious violations of basic journalistic ethics and integrity.”

As Koppel and the winners were celebrating in the upstairs ballroom of the Waldorf Astoria, Nate Thayer sat alone in the downstairs bar, and told his tale of woe to the bartender. “He said, ‘I like a guy with principles, the drinks are on me.’” he recalled. “I got double scotches for free.”

While Nate Thayer was correct that corporations had taken over media and their culture now ruled journalism, his decision to make a handshake deal with ABC was a bad one that he had been warned about. “I’d argue, he didn’t handle fame well, yet secretly craved it,” wrote journalist Mark Dodd. “His tobacco spitting bravado masked nagging insecurities which would plunge him into deep depression and bitterness.” So began a streak of pyrrhic victories that would shape the sad, second half of what, up to that point, had been a meteoric career that had just apexed with the biggest scoop of the post-World World II period.

My god ... what a story!