This is Part 6 in Sour Milk’s Ukraine series. You can read Part 1 here , Part 2 here, Part 3 here, Part 4 here, and Part 5 here.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s call for Russian President Vladimir Putin to be tried by a court “similar to the Nuremberg tribunals,” coupled with President Biden’s and Prime Minister Johnson’s charges that Russia is committing “genocide,” is nothing less than a call for regime change in Russia. It will be impossible to try Putin without Russia’s unconditional surrender or a coup and the cooperation of the successor regime. Only victors can try the vanquished in war crimes trials that involve members of the United Nations Security Council.

I have few doubts that Russia has committed “war crimes” in Ukraine. Earlier this week my associate, Nug, traveled to Bucha and watched French investigators exhume bodies from a mass grave. He examined numerous civilian vehicles whose drivers were cut to ribbons and burned alive by machine guns, 20mm cannons, missiles, and anti-tank weapons. “One car’s floor was covered with a layer of rock hard, coagulated blood, and the inside spattered with bits of dried brain matter,” said Nug. “One woman identified her father’s car. All that was left of him was the burnt tip of his thigh bone and his lower jaw, she was inconsolable. It was a long, sad day.”

In order for any court to build a legitimate war crimes case, independent investigators must collect forensic evidence and link it to the perpetrators. Charges of genocide and aggressive war are, however, more complex because prosecutors must prove that the defendant’s actions were part of a conspiracy or common plan ordered by Russia’s leaders. Further complicating matters is the fact that the International Criminal Court (ICC) has no jurisdiction over Russia. Like the United States, they are not signatories to the ICC.

These legal questions are simple compared to the political questions that surround a possible war crimes trial. From 1949 to 1991, war crimes trials were confined to garden variety war criminals, bloodstained “bad apples” like William Calley, Treblinka commandant Franz Stangl, and other convenient scapegoats. Atrocities committed by UN Security Council powers and their puppet regimes were off limits from international legal scrutiny. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Cold War’s harsh strategic legalism turned into something more timid and therapeutic.

After genocides in Rwanda and former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, the mantra “Never Again” morphed into “I am sorry.” Instead of Apache gunships and the decisive use of force, the West and the United Nations promised victims post-tragedy justice in the form of war crimes trials. There was a growing acceptance of the idea that it was permissible to stand aside and watch knowingly as genocide was carried out on live television, as long as a dozen or so ringleaders would be solemnly indicted and tried by an international tribunal in the not-too-distant future. However, the actual application of justice was selective, proving once again that the rules of international law do not apply equally to all.

As the decade wore on, a new generation of activist journalists and human rights advocates appropriated “the legacy of Nuremberg” to justify an International Criminal Court empowered with “universal jurisdiction.” Some made extremely broad and unsubstantiated claims about the therapeutic benefits of war crimes trials—not only would they punish the guilty and exonerate the innocent, they would also provide “truth,” “reconciliation,” “healing,” and “closure” because, these advocates claimed, that is what Nuremberg had done for the Germans. According to this most recent myth of Nuremberg, the landmark trials did not simply determine legal innocence and guilt, they brought about a West German national catharsis during the 1950s. Conspicuously absent were references to the British, French, and American war crimes clemencies of the 1950s, not to mention the West German rejection of the legal validity of all the Allied postwar trials.

Some believed that universal jurisdiction would fix the fundamental flaw of international law since the time of Hugo Grotius: the ability to enforce it. Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Tina Rosenberg offered this application of the theory: “If the Spanish government had discovered Lt. William Calley vacationing in Barcelona and America had refused to put him on trial, Spain would have been within its legal rights to have held him and brought him to justice for the My Lai massacre in Vietnam.”

More troubling than the war crimes trial triumphalism was the fact that few of the assumptions stood up to analysis. Not only were important parts of the “legacy of Nuremberg” left out, criticism beyond the ritualistic complaints about ex post facto law and victor’s justice was considered to be in bad taste in anything but far left and far right academic circles. As a result, analysis of the trials rarely went deeper than American prosecutor Robert Jackson’s opening address. Rather than face profound questions about the relationship between national sovereignty and “universal jurisdiction,” the UN and human rights industry leaders focused their vast resources on procedural questions, and legal minutiae.

There was a flurry of diverse, and often contradictory, international legal activity in the 1990s: UN war crimes courts were established; sitting leaders were indicted during wartime; an American court applied the Alien Tort Claims Act and tried Yugoslavian leaders in absentia; the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission traded amnesty for testimony; a Belgian court considered cases against Henry Kissinger and Ariel Sharon; and there was an unsuccessful attempt to try Chilean leader Augusto Pinochet.

The “human rights era” reached its shrill climax during the spring of 2001. First, British journalist Christopher Hitchens attempted to indict and try Henry Kissinger in the pages of Harper's Magazine. Next, Samantha Power called for a Senate Investigation of Bob Kerry's alleged atrocities during the Vietnam War. Irrespective of all of the new found interest in international law during the 1990s, the basic distinction between soldier and civilian all but disappeared in places like Sarajevo, Kigali, Dili and Freetown. The handful of policymakers tried in the Hague, Arusha, and elsewhere—Serbia’s Slobodan Milosevic, Rwandan Jean-Paul Akayesu and others—were the leaders of third tier nations who disobeyed or displeased their international political masters. Members of the UN Security Council remained strictly off limits.

The 9/11 attacks ended the human rights era with an exclamation point. Unlike previous American presidents who claimed to support international law when the outcome was favorable to the United States, President Bush explicitly rejected both long-standing, codified laws of war like the Geneva Conventions and argued that there were no limits—constitutional or congressional—on presidential authority. President Bush declared that the “War on Terror” was a new kind of war requiring “a new paradigm” that would render the Geneva Convention’s strict limitations on the treatment of enemy prisoners “obsolete.” Brazen disregard for the laws of war was soon elevated to a matter of principle as America began a sordid affair with what Vice President Cheney described as “the dark side.” After 9/11, human rights utopians shifted into hard nosed realists and joined the neo-imperialists in their call for America to strike out preemptively against threats both real and imagined.

President Bush officially declared war on international criminal law when he unsigned the Rome Statute establishing the International Criminal Court in July, 2002. A federal law called the American Service-Members’ Protection Act (better known as the Hague Invasion Act), passed in August, 2002, authorized the President to use “all means necessary and appropriate to release US prisoners of the ICC.” The Bush administration also began suspending aid to countries that refused to give U.S. citizens immunity before the ICC.

Although the term “enemy combatant” was used as a strategic legal mechanism to get around international humanitarian law, when all else failed, the Bush administration invoked simple messianic unilateralism. “Good” and “evil” became the new “metrics” for a vague new American foreign policy whose exponents claimed to be on a crusade to rid the world of “evil” and to spread “freedom.” By the time the United States invaded Iraq in 2003, extraordinary rendition, secret “black site” prisons, torture, indefinite detention of American citizens, domestic espionage, and watchlists were all accepted as facts of life by a stunned and submissive American population who viewed the havoc wrought in their name from afar.

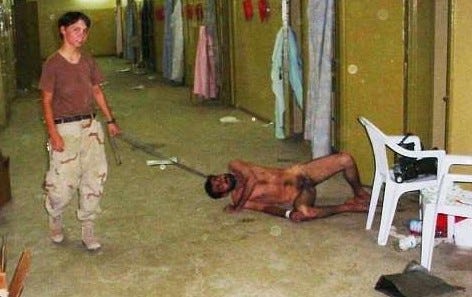

That arm’s-length relationship was shattered in 2004 when General Anthony Taguba’s report on prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib was leaked to Seymour Hersh, and photographs of American soldiers perversely torturing and humiliating common Iraqi criminals flashed around the world in seconds. Bin Laden himself could not have staged a more successful propaganda coup as smiling, fresh-faced American girls led naked Iraqi men on leashes. One senior policymaker described the perpetrators to me as “the seven soldiers who lost the war.” Similar to President Theodore Roosevelt’s response to atrocities in the Philippines War or President Nixon’s response to the Mai Lai Massacre, the perpetrators were deemed “bad apples,” their actions “isolated events.”

When it came to war crimes trials for the vanquished, the Bush administration employed traditional, primitive political justice. As a result, it could not even provide an easily convicted thug like Saddam Hussein with a decent show trial. The fallen Iraqi leader’s chaotic American-choreographed proceeding saw lawyers murdered, courtroom brawls between defendants and guards, and even an execution video on YouTube before it made the morning papers.

The war crimes trials at Guantanamo Bay were and remain a national embarrassment like the U.S. Dakota War Trials (1862) and the Yamashita case (1945). Under GITMO’s everchanging rules, prisoners can be held indefinitely without charges, torture induced confessions are considered admissible “evidence,” and even those defendants who are found not guilty can be “held in perpetuity.”

The Cuban camp, however, has served as an important distraction from the CIA’s archipelago of secret prisons where “high-value” detainees are tortured, interrogated, and sometimes killed. War crimes committed by UN Security Council powers—the American invasion of Iraq and the systematic use of torture in the Global War on Terror, China’s ongoing genocide of the Uyghur ethnic minority, Russia’s invasion of Chechnya—were still strictly off limits.

During his presidential campaign, President Barack Obama promised to close Guantanamo Bay and reevaluate America’s floundering Global War on Terror. However, under his weak-willed watch, Obama continued and even expanded the neoconservative efforts to create an America-friendly, “Greater Middle East.” Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, National Security Advisor Susan Rice, and UN Ambassador Samantha Power accelerated the pace of an expensive and doomed counterinsurgency war and nation building exercise in Afghanistan, announced the U.S. withdrawal from Iraq and then allowed ISIS to fill the power vacuum, overthrew the government of Libya, and attempted to do the same in Syria. At the time, David Rieff presciently observed that there was only one degree of separation between the neoconservatives and humanitarian hawks.

Despite the presence of the United Nations, the International Criminal Court, the European Union, and NATO, very little has changed in international politics since Thucydides famously wrote in 404 B.C. that “the standard of justice depends on the equality of power to compel and that in fact the strong do what they have the power to do and the weak accept what they have to accept.” Today, despite the most comprehensive set of laws governing war and international relations in human history, the oldest and most basic distinction, the one between soldier and civilian, continues to disappear. While Ukraine might have successfully defended their capital and bloodied Russia in the process, with Putin now being threatened with the a seat in a defendants’ dock, this war is far from over.