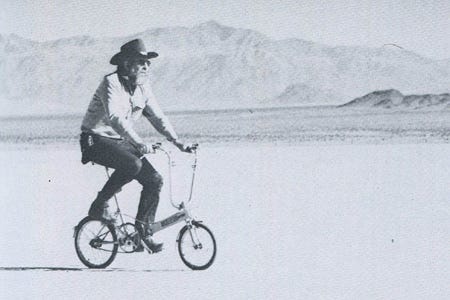

British architectural historian, Reyner Banham, loved Los Angeles because it was a city that broke all the rules and made “nonsense of history.”

While he was enamored by the San Diego Freeway, the car culture, and the Southland’s beaches, he was most impressed by its “preferred form of the noble savage”—the surfer. In 1969, the tall, bearded Englishman wrangled an invitation to surfer/artist Jim Ganzer’s Topanga beach house.

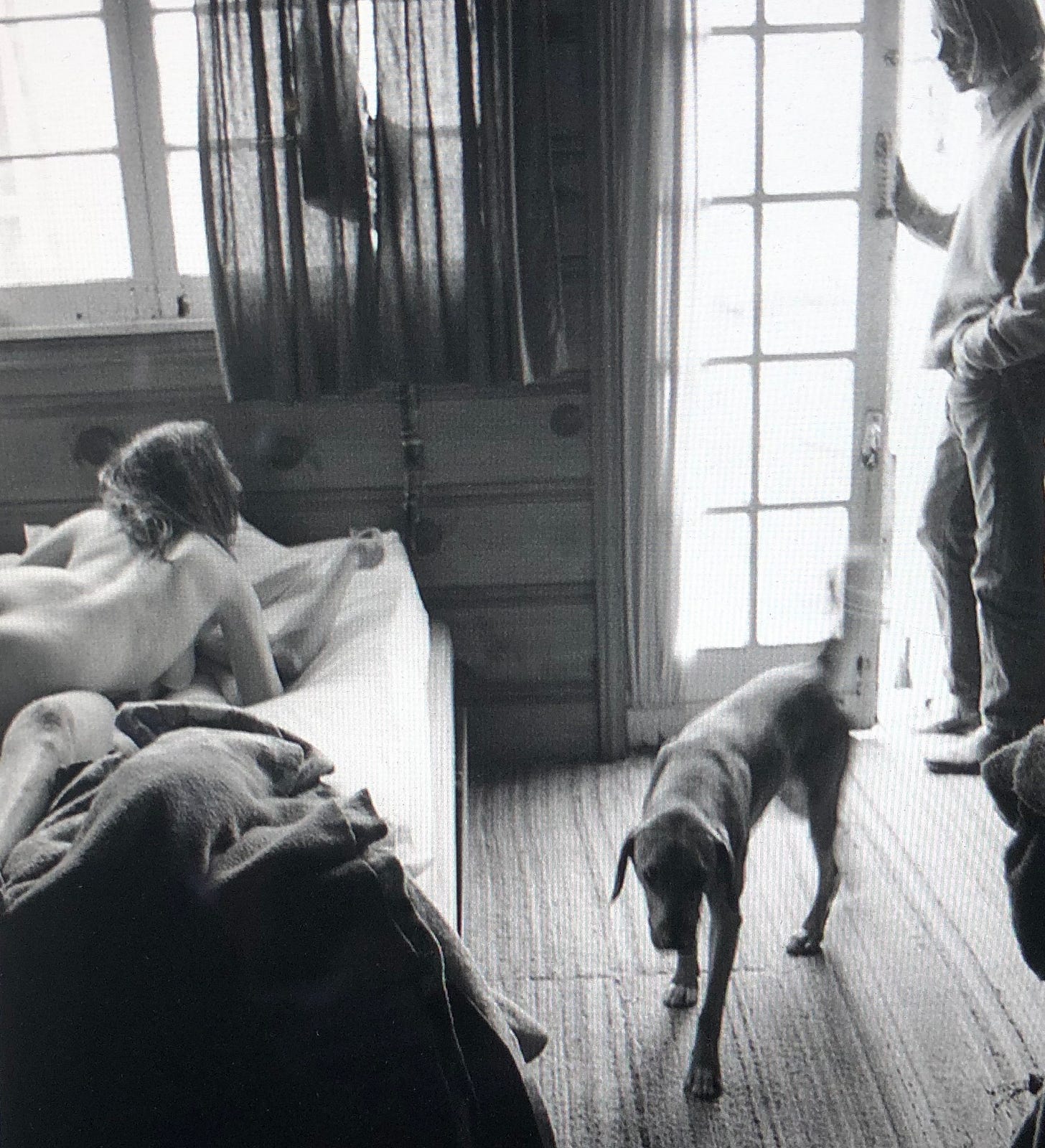

Between Pacific Palisades and Malibu, there once sat a Dionysian enclave of beachfront houses that looked out onto a private point break. “Topanga was quite a place at that time, you had the hippies, the nude beach, and even the Manson family for a while. You didn’t surf there unless you were invited,” recalled Ganzer. “Banham was struck by my hedonistic view of life. He said, ‘This is just one big amusement park.’”

Born in Chicago in 1945, Jim Ganzer’s father worked for the Pullman railroad car company. When the trains began to die and airplanes began to fly, he cashed his bonus check, bought a white, Pontiac convertible, and drove his family west on Route 66 until they hit the Pacific Ocean. Fourteen-year-old Jim arrived in Pacific Palisades, California, in September of 1957. He had greased-back hair, a brush in his back pocket, a Levi’s jacket, and horseshoe heel taps on his loafers. Very soon, he would swap his denim jacket for a Pendleton shirt and his loafers for Jack Purcell tennis shoes.

On one of his first days in the Palisades, Ganzer walked to the beach and met a group of kids his own age bodysurfing near the Bel Air Bay Club. One of them was Robbie Dick, son of a UCLA literature professor, who would go on to become one of the region’s great underground surfboard shapers. “I knew nothing about surfing or the ocean,” said Ganzer. “There was a big, south swell and the waves were pretty big, I got thrown around and thought, ‘Fuck this is really something! This is scary!’ Immediately, the ocean was a big deal to me.”

By the fall of 1958, Jim Ganzer was surfing. Before Santa Monica’s Dave Sweet invented the foam and fiberglass surfboard in 1956 (two years before Hobie Alter and Gordon Clark), surfing “remained a tough and restrictive sport,” wrote Reyner Banham in his seminal work, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies. “What has happened since is—as they say—history, but few episodes of seaside history since the Viking invasions have been so colorful.”

Jim Ganzer’s new hometown was ground zero for a baby boomer-led cultural revolution because, as Banham pointed out, the “culture of the beach was a symbolic rejection of the values of the consumer society.” By the time he arrived, Will Rogers State Beach, Pacific Palisades above it, and Santa Monica Canyon behind it had been home to a vibrant Southern California “waterfront culture” for almost a century. British writer, Christopher Isherwood, who moved to Santa Monica Canyon in 1953, called it the “western Greenwich village” and described it as a place where “cranky, kindly people live and tolerate each other’s mild and often charming eccentricities.”

If you walk down Channel Road towards the Pacific Coast Highway, the smell of piss will lead you to a subterranean staircase and a tunnel under the PCH that will take you to “State Beach.” “All of us congregated at State Beach because it had something for everyone,” recalled Ganzer. “There was a Hollywood scene, a volleyball scene, a surfing scene, a gay scene, and nightlife in the Canyon.”

“Next to the gay bar, the S.S. Friendship, was a bar the older surfers went to called ‘Big Tom’s,’ and rumor had it that you could buy ‘grass’ from the bartender.”

What Jim Ganzer liked most about State was the sense that anything could happen at any time: “One day we were on the beach and spotted a ring of guys in dark suits. Next thing you know, we hear the beat of chopper blades, a helicopter touches down in front of Peter Lawford’s house, and JFK jumps out. In 1964, Daryl Stolper and I were at State and the Rolling Stones showed up looking for him. Daryl had been collecting blues records since he was a little kid and the Stones wanted to buy records from him.”

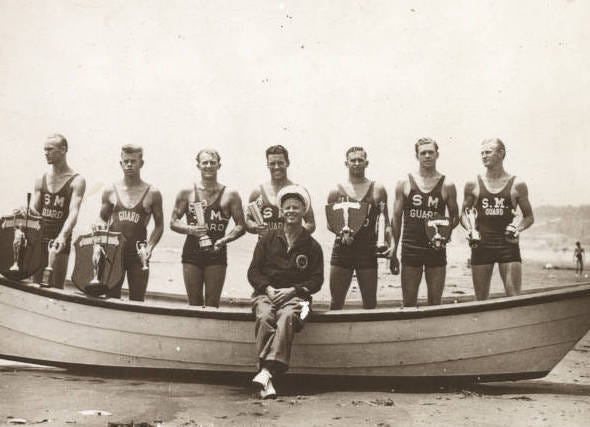

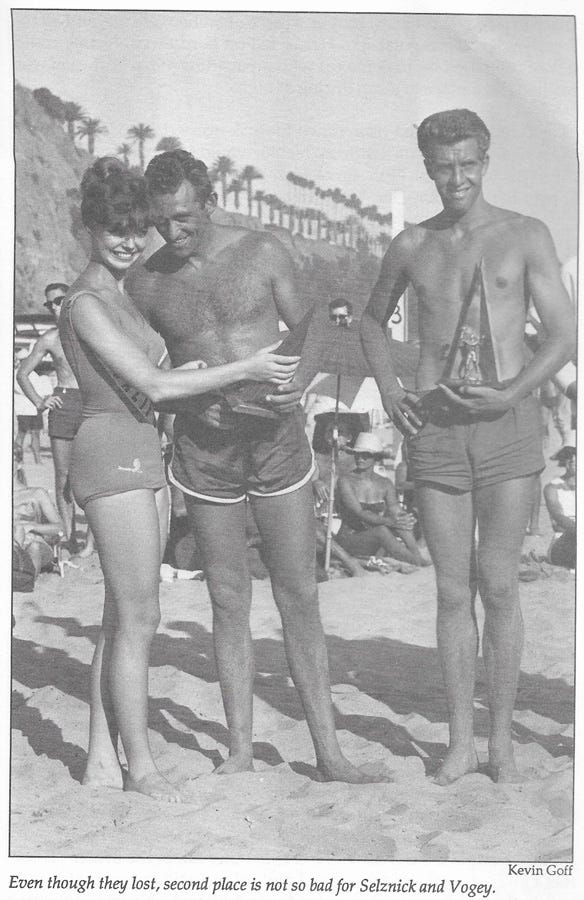

While the first “King of the Beach,” Gene Selznick, ruled the volleyball courts, generations of Santa Monica’s legendary watermen ruled the surf.

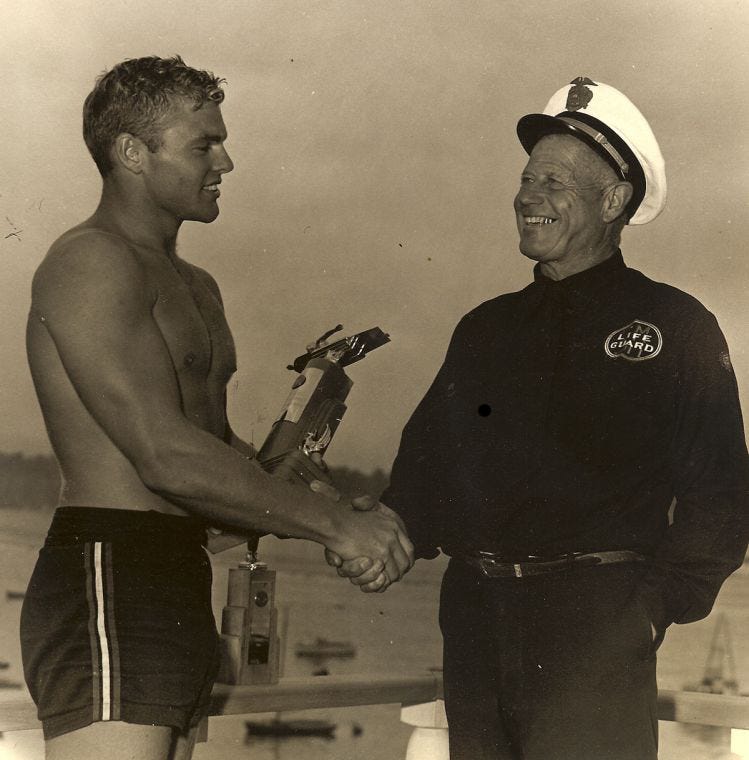

What do George Freeth, Duke Kahanamoku, Tom Blake, Pete Peterson, Tom Zahn, Joe Quigg, Ricky Grigg, Peter Cole, Buzzy Trent, Mickey Munoz and Mike Doyle all have in common? These founding fathers of surfing all served as Santa Monica lifeguards.

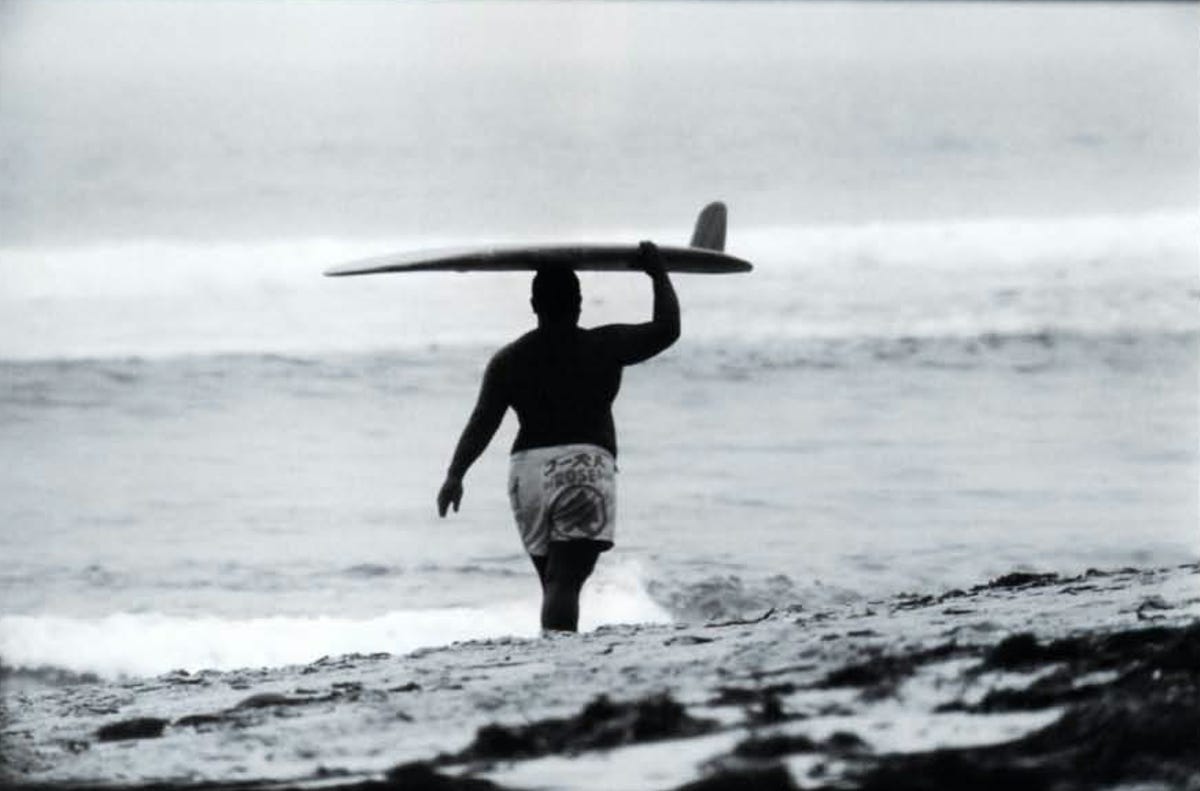

The word “waterman” once carried great weight. It was the maritime equivalent of a black belt in a great martial art. It was not enough to surf. A waterman had to have mastered all the aquatic arts: he was a skilled diver, canoe surfer, oarsman, meteorologist, sailor, ocean swimmer, body surfer, lifesaver, fisherman, spearfisherman, and board/boatbuilder who could ride any size surf on any craft put beneath him.

Jim Ganzer’s surfing role models were Herculean figures like Santa Monica lifeguards Tom Zahn and Pete Peterson. Each morning, Ganzer and his friends would watch lifeguard, surfer, and champion paddleboarder Tom Zahn launch his board in the shore break and practically disappear over the horizon on his daily marathon paddle.

In addition to winning surfing, paddling and tandem surfing contests from the 30s through the 60s, Peterson was also a stuntman, a hard hat diver, inventor of the lifeguard buoy, and a marine salvage expert.

“He was a big, quiet guy who lived in Santa Monica Canyon. He was in the ocean every day and was just a waterman extraordinaire,” said Ganzer. “We were all in awe of him.”

The teenager’s entry into surfing was eased by his friend, Denny Aaberg, who lived next to Palisades Park. Kemp, the oldest Aaberg brother, was a lifeguard at Malibu who gained a modicum of surf stardom when a photograph of him arching across a sparkling Rincon wall became Surfer Magazine’s first logo (he was also one of the featured surfers in Bruce Brown’s 1958 film Slippery When Wet): “We all looked up to Kemp because he was a lifeguard and a great surfer. He and his good friend, Lance Carson, were the two best surfers in Pacific Palisades. He drove this funky car that always had surfboards sticking out of the back. ”

What Ganzer remembers most about Kemp is his room, because it was a veritable shrine to surfing. “The walls were covered with surf pictures. Kemp had a poster of Jim Fischer riding a giant wave at Makaha that he called ‘Fischer’s Wave.’ I was terrified by it and asked him, ‘What do you do if one of those breaks on you?’”

“He answered my question with a story. There was a story behind every picture and every piece of memorabilia. Going into that room was like going into a museum and he was the docent. It really made me want to become a surfer.”

Middle brother, Steve Aaberg, lived in the garage. His walls were covered with vinyl 45 records, grass mats, neon beer signs, and the only furniture was tuck-and-roll car seats. “Steve was a super built gymnast who always wore his black and gray ‘Deacons’ car club jacket,” recalled Ganzer. “He was a badass. Not only did he have a gold and white Chrysler DeSoto hotrod, he also painted his motorcycle gold and white to match it.”

When Jim Ganzer told Steve Aaberg that he had tried surfing and wanted to buy a board, Aaberg said, “‘I just happen to have one for sale’ and headed towards the back of the house. A few minutes later, he came back with a battered, balsa Velzy and Jacobs that had a foam nose. ‘$40,’ he said. So I come back with $40 and he says, ‘$45!’ I get all disgruntled, go away, and come back with another $5. When he said, ‘I want $50!’ I said, ‘Fuck you!’ Steve laughed and said, ‘OK, OK’ and sold me the board. This was the era of the rat fuck. I learned young to watch my back and stand my ground.”

Jim Ganzer and his friends, Robbie Dick, Lanny Hoffman, and Denny Aaberg, surfed State Beach as much as they could, and they progressed quickly. Soon they all had knots on their knees and crater-like open sores they called “volcanos” on the tops of their feet. “We used to compete to see who had the most flies around their craters,” said Ganzer. Their favorite place to surf was in front of Mike Doyle’s lifeguard tower just south of State. “We knew Doyle from the Aaberg’s house,” said Ganzer. “He’d come up to see Kemp all the time in his woody he called ‘The Trestle’s Special.’ When we’d come in from surfing, Doyle would let us sit in the tower, and he would critique our surfing and give us pointers, ‘I liked it when you did the nose tweak and then hung five.’ He was a really nice guy and eventually got all of us on the Hansen surf team.”

Mrs. Aaberg was from East Texas and “even though she was tiny, she was a big person and very smart. She wore her hair in a bun and was pretty unflappable. She’d just shake her head and say, ‘You boys!’ Big Wednesday could have been so much better if it had been about the Aaberg brothers and the dynamic between them and their divorced mother.” What Ganzer remembers most about the Aabergs’ house is their parties (immortalized in the film Big Wednesday).

“Denny would say, ‘Hey! They’re having a party! Come by!’” Ganzer remembers the summer night he approached the Aaberg’s house and heard Fats Domino’s “Blueberry Hill” floating through the balmy nighttime air. As he walked around Dewey Weber’s 1933 Ford panel truck that was parked on the lawn, he almost bumped into a guy taking a piss: “He had one arm around a girl, a gallon jug of Red Mountain Wine in his other hand, and a girl holding his pecker. Inside the house, these older, beautiful, stylish girls were doing ‘The Slow Wicked Stroll’ to Bill Doggett’s song, ‘Honky Tonk.’”

At one party, Henry Ford got especially drunk, so they covered his face with peanut butter and stuffed him into the oven. These gatherings were as much tribal councils as they were social events. Duke Boyd, Henry Ford, the lifeguards, and the best South Bay and Malibu surfers all attended. “At some point in the night, the hodads, the guys with their hair slicked back into ducktails, would show up to trash the party. The surfers would close ranks and kick their asses,” said Ganzer, “The kids ran the show at the Aabergs’ and the neighbors were aghast!”

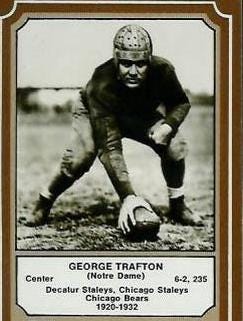

There was, however, one neighbor who was not aghast and who nobody fucked with: Mr. Trafton. NFL hall-of-famer George “The Brute” Trafton was the star center on Knute Rockney’s famous 1919 Notre Dame (“win one for the Gipper”) team, then played for and coached the Chicago Bears, and wrestled and boxed professionally. Red Grange called Trafton “the meanest, toughest, player alive.” Although he was old, “Mr. Trafton carried a big cane with a giant hook handle that he used to hook around people’s necks and pull them close for a little chat.”

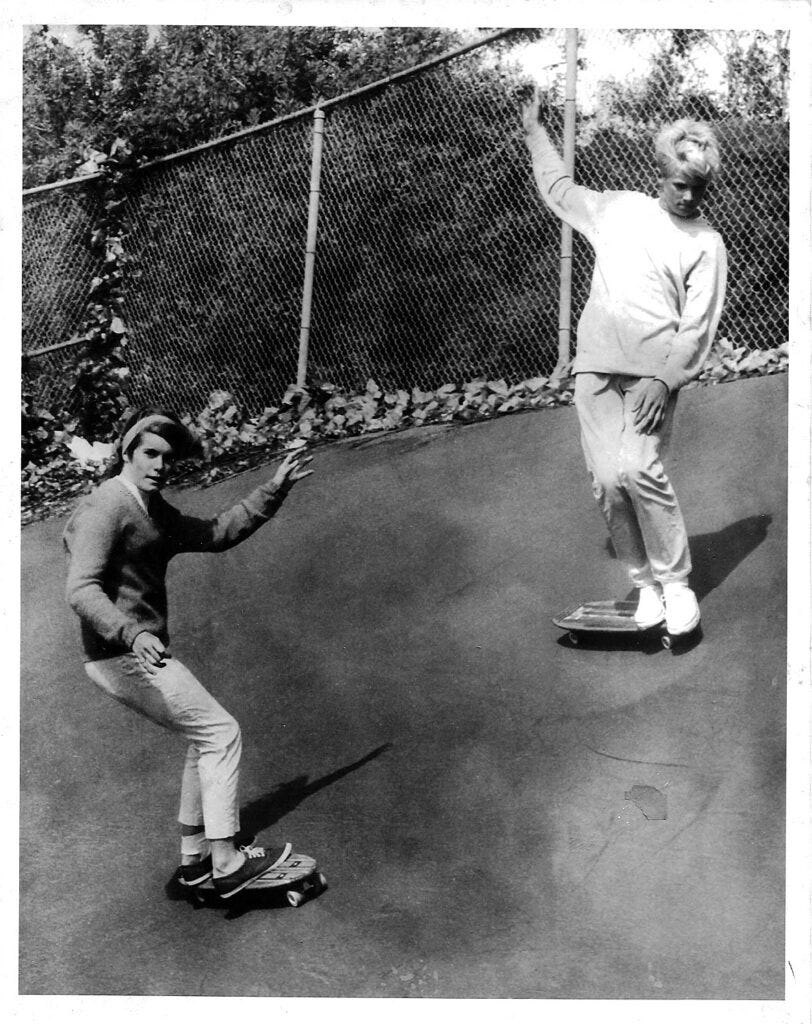

His son, George Jr., was younger than Ganzer and always hanging out of his bedroom window checking out the action at the Aaberg’s house. “One day we were nailing iron wheels onto 2x4s, making the first skateboards, then pretending that we were surfing on the sidewalk. George Jr. leaned out his window and asked, ‘Hey, what are you guys doing?’ The next thing you know, he’s down there skateboarding with us, and in what seemed like a few weeks, he was better than all of us,” said Ganzer.

“People have lost sight of the fact that skateboarding’s true ground zero was Pacific Palisades. More than a decade before Dogtown, Woody Woodward, George Trafton, Danny Bearer, Jim Fitzpatrick, John Fries, Scott Archer, Steve and Davey Hilton, Torger Johnson and a handful of others, were the first pioneers.”

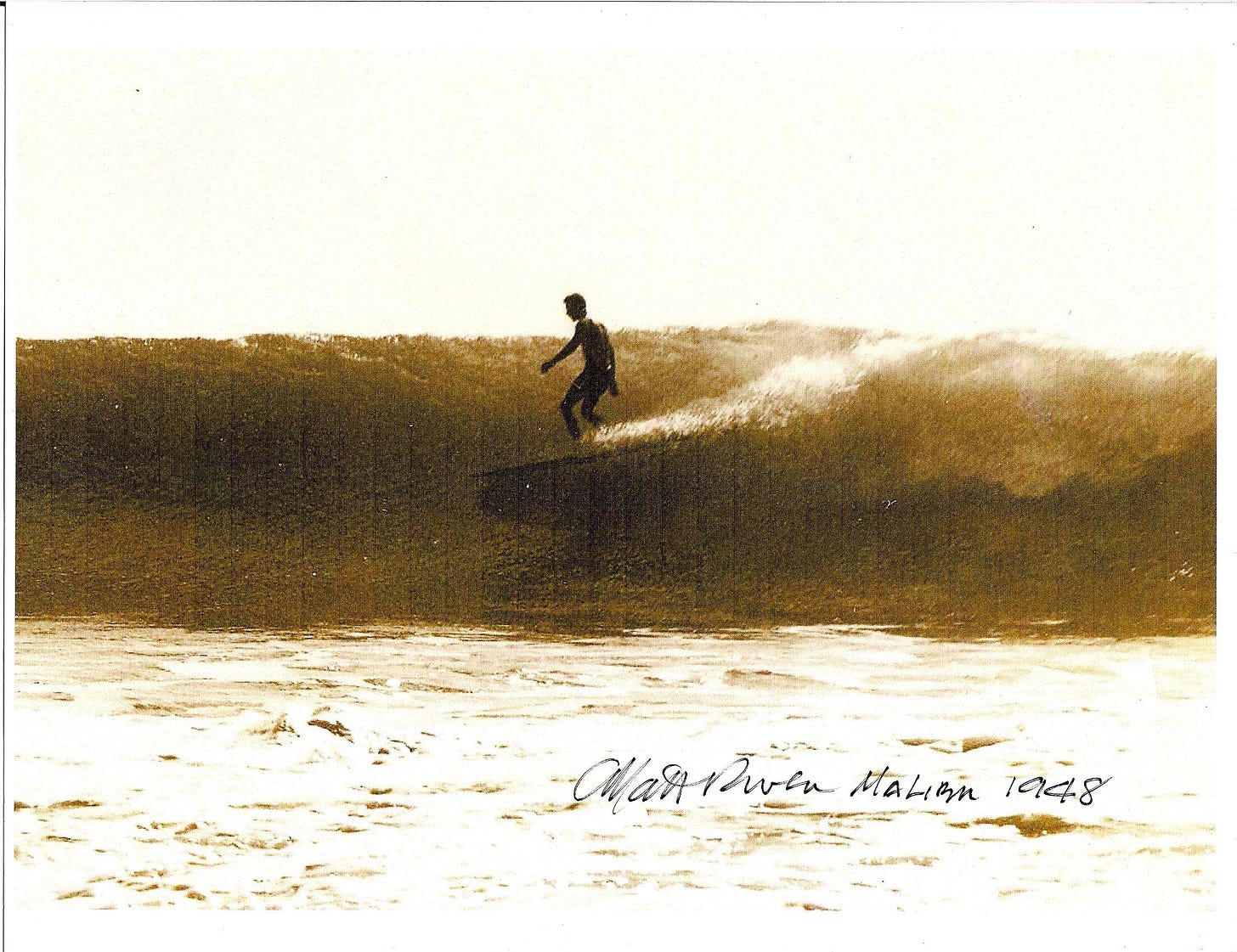

The first time Jim Ganzer went to Malibu he hitchhiked there and the waves were firing.

“Malibu was much more of a frontier town back then,” said Ganzer. “There were no cops except for Broderick Crawford driving around drunk in his fake police car.” Unlike Santa Monica’s athletic, waterman culture, Malibu was a lawless, libertine place that was home to “dropouts” and “surf bums.”

When Ganzer spotted a barbed wired area filled with discarded furniture and a palm frond hut, he paused because he knew that this was “The Pit,” the notorious place he had been warned about. “I tried to sneak by The Pit unnoticed but was intercepted by a sinister guy I had once seen tip over an armoire at a party. After all the china inside shattered, he laughed maniacally. First, the guy made me stand at attention as he rifled through my possessions and took anything of value. Then, he called over one of his stooges, a guy I knew from the Palisades, and barked, ‘Hit him!’ I could tell he didn’t want to do it, but he punched me in the stomach.”

Jim Ganzer went home so upset that his father immediately noticed something was wrong. “My dad and his brothers were all tough guys from Chicago. He did not raise me to turn the other cheek. After I told him what happened, he took off his wing tips, put on tennis shoes and a tee shirt, and said, ‘Get in the car!’ I’d never seen him like this.”

The Ganzers pulled up to his assailant’s house, and his father answered the door. Mr. Ganzer said, “‘I think your son would like to speak to my son.’ The man sensed that something was up and probably realized his son was out of line and said, ‘Come on down, there are some guys here who want to talk with you.’ He stayed upstairs and wouldn’t come out of the house.” It all worked out in the end, as Ganzer was at Malibu the day his sinister Pit tormentor got his comeuppance, “He was eating a half a watermelon and some guy he had obviously wronged walked up and punched him in the mouth right through the watermelon and dropped him.”

The Ganzers were a family of athletes, and although Jim had been an excellent wrestler, football, and baseball player in Chicago, once in California, he drifted away from team sports. “The coaches didn’t like surfers,” said Ganzer, “When Robbie Dick and I went out for football, the coach said to us, ‘Oh no! I know you guys. When the first good swell comes, you guys are going to Malibu!’”

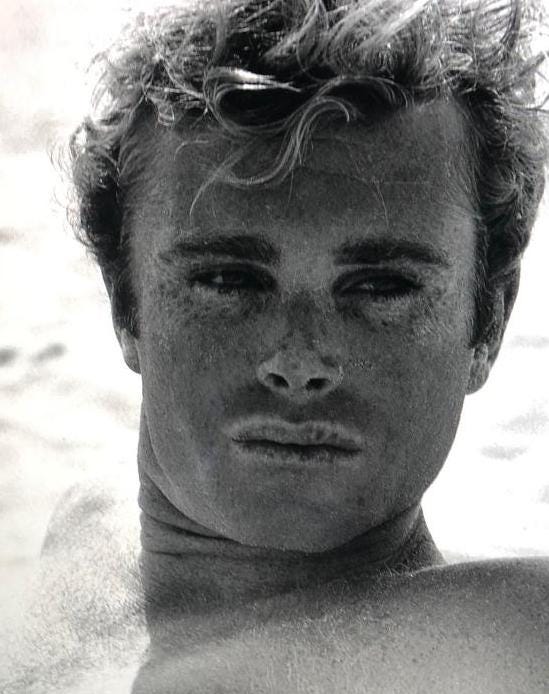

The coach was right, they were spending more and more of their time at Malibu where they became friends with locals like Ray “The Enforcer” Kunze, Mysto George, Tim “The Glider” Lyon, and also got to know more ominous characters like Miki Dora, bank robber Eddie Lavo, Hawaiian transplant “Mokey,” and Malibu’s dignified resident hobo “Old Joe.” “Originally from Italy, Old Joe came to Malibu to work making tiles at Malibu Pottery and never left,” said Ganzer. “He was a proud guy who always wore a suit, refused handouts, and was always a perfect gentleman. There were some real characters at the point who had a very inventive attitude towards life.”

After Ganzer got a job hosing the fish guts and scales off the Malibu pier, he and his friends often spent the night on the beach up by Third Point and Malibu Colony. Many of Malibu’s local surfers lived in Malibu Colony, the movie star enclave just north of the point. “There were some great surfers from the Colony. Butch Linden, the Horner brothers, Jim Rapf and, of course, Johnny Fain. Johnny was a great surfer who had a big bottom turn and a really dramatic cutback. He was a total hustler, at one point I think he was Malibu Colony’s tennis pro,” said Ganzer. “He and Miki used to play tennis. They had a love/hate relationship. Most people just accepted the fact that Miki was going to stooge you, but Johnny didn’t stand for it at all. He had a sense of self-importance and once Miki realized that, it was over.”

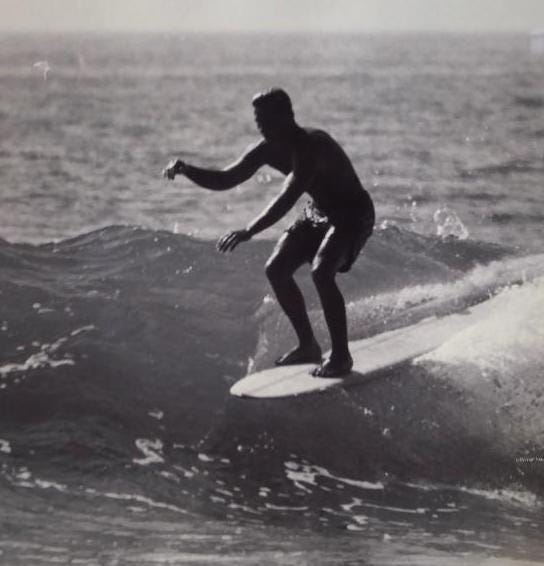

When it came to surfing The Point, nobody rode the nose better than Lance Carson. “He started surfing really young. His dad made him these miniature boards and used to take him up to The Point. Lance had more of an upright, bob-and-weave style and did amazing tail block stalls. This was very different from Miki Dora and a lot of the Malibu guys who had more of a smooth, narrow-stanced, trimming style.

“Miki would move 3/4s up his Yater spoon, get in the dish, and do his sashay turns from there. Dora’s boards had soft rails, and he’d make them go rail to rail and when it washed down to the bottom of the wave, he’d set the inside rail, and woosh! Dora’s stance was almost parallel at times with a slight arch. If you’re really in trim, all you have to do is move your head to adjust. The arch isn’t just a pose, the arch is a practical move—there’s substance in that style.”

When the big, south swells hit, everyone made their summertime pilgrimage to Malibu: Actor Peter Lawford, LA Times owner Otis Chandler, Tom Morey, Joey Cabell, Bob Cooper, and many others showed up at The Point. “I remember Chubby Mitchell pulling up to The Point in a stand-up drive mail truck full of the guys from the South Bay. Chubby was 5’9”, close to 300 pounds, he rode a 13’ tandem board, and was such a nimble surfer,” recalled Ganzer.

“Dewey Weber and the South Bay guys had a very different, bob-and-weave style. I think it came from Phil Edwards. These summer swells were a real gathering of the tribe. Photographers Grant Roloff, Bud Browne, and Don James would all have their cameras set up on the beach.”

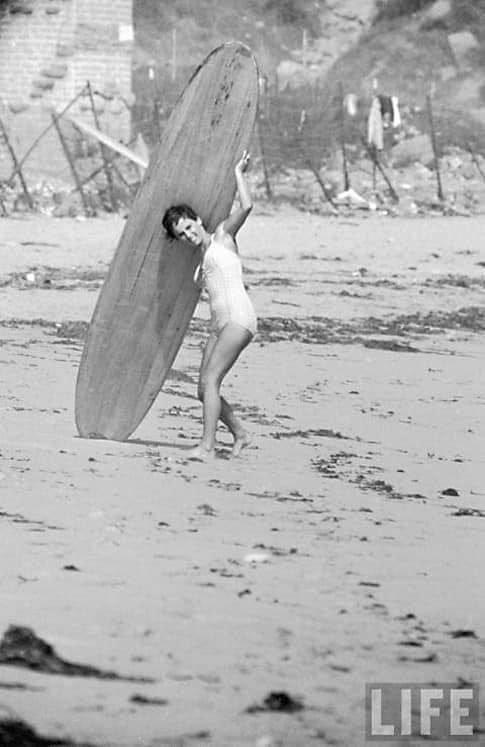

The film Gidget came out in the spring of 1959, and Jim Ganzer and Denny Aaberg saw it on opening night at the Bay Theatre in Pacific Palisades. “There was a big line out front, cars were cruising by honking their horns, guys doing BAs out the window, it was a big scene. We go to the ticket booth and a small, cute brunette, a little older than us, handed us our tickets. Denny said, ‘Thanks, Gidge.’ We got out of ear shot and Denny turned to me and said, ‘That’s her, that’s the real Gidget.’” Kathy Kohner Zuckerberg, the daughter of German émigré screenwriter Frederick Kohner, grew up in the Palisades and learned to surf at Malibu. She told her father about the characters she met at Malibu and all the dramas she witnessed. “He wove them into the book Gidget that was a huge hit when it came out in 1957, but when the movie came out in 1959, forget it, everyone wanted to become a surfer.”

Read “West of the 405 - Part Two” here.

One more generation and all of this will be lost to the wind. It's nice that you are capturing these little snapshots of American history. The era you describe might have actually been the high water mark.