This is Part Two of “The Most Beautiful Man in the World.” You can read Part One here.

By the time Gene LeBell agreed to fight against a boxer in Salt Lake City, Utah, in a $1000 winner-take-all challenge match, he was one of the most despised “heels” in professional wrestling. In the lingua franca of pro wrestling, a “heel” is a bad guy who is typically pitted against a good guy or “face” (short for “babyface”) in a “worked” match. A “work” is a fixed fight in which the loser helps “put over” the predetermined winner in a realistic way so that the audience does not realize that the fight is fixed. Works, however, are delicate dances that sometimes devolve into brawls. Although world champion wrestler Lou Thesz would take dives against inferior opponents, if that opponent tried to make a fool out of him, according to LeBell, “Lou would hurt him.”

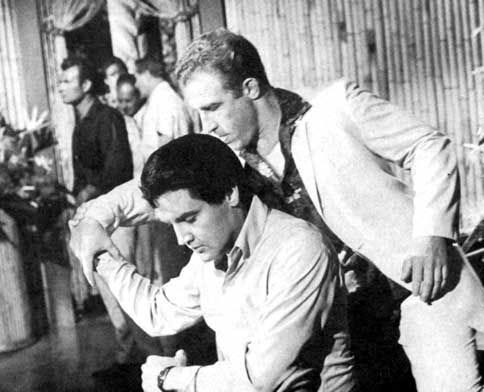

To Gene LeBell, who grew up in Hollywood, pro wrestling was just another part of his life in show business. By 1960, LeBell had been punched out by John Wayne in Big Jim McLain, subdued by George Reeves in The Adventures of Superman, smashed into a wall by David Nelson in The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, and thrown by Elvis Presley in Blue Hawaii. “We performed in anything and everything back then,” he said. “There were only about fifty stuntmen back then and you worked every day.”

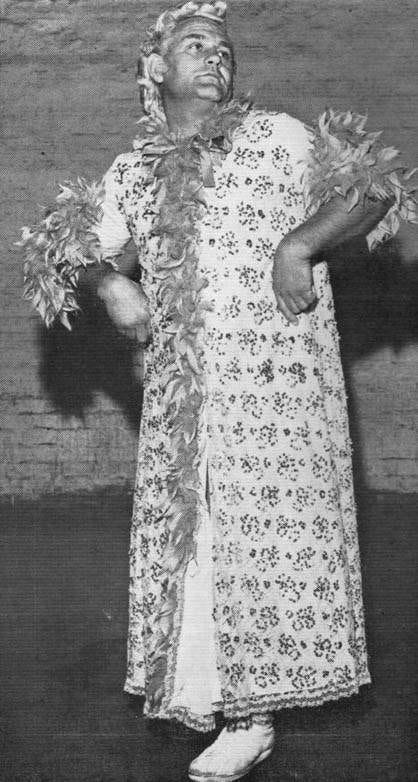

LeBell’s mother, Aileen Eaton, helped transform a mediocre wrestler named George Wagner into “Gorgeous George,” the biggest attraction in pro wresting in the 1950s. The effeminate wrestling heel became famous for his platinum blonde hair, gold bobby pins, and valet “Jeffries,” who sprinkled rose pedals in his path and sprayed the ring, and often his opponents, with what he claimed was “Chanel #10” perfume.

LeBell described the first time he saw Gorgeous George fight, “I looked around and saw everybody was mad. I was mad! Fifteen thousand people coming to see this man get beat, and his talking did it. I said, ‘This is a good idea.’”

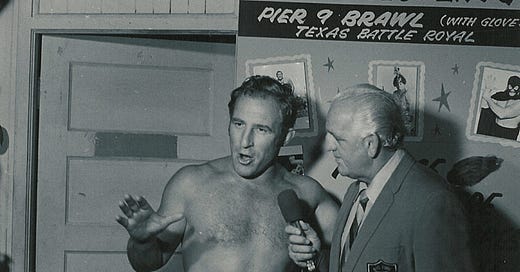

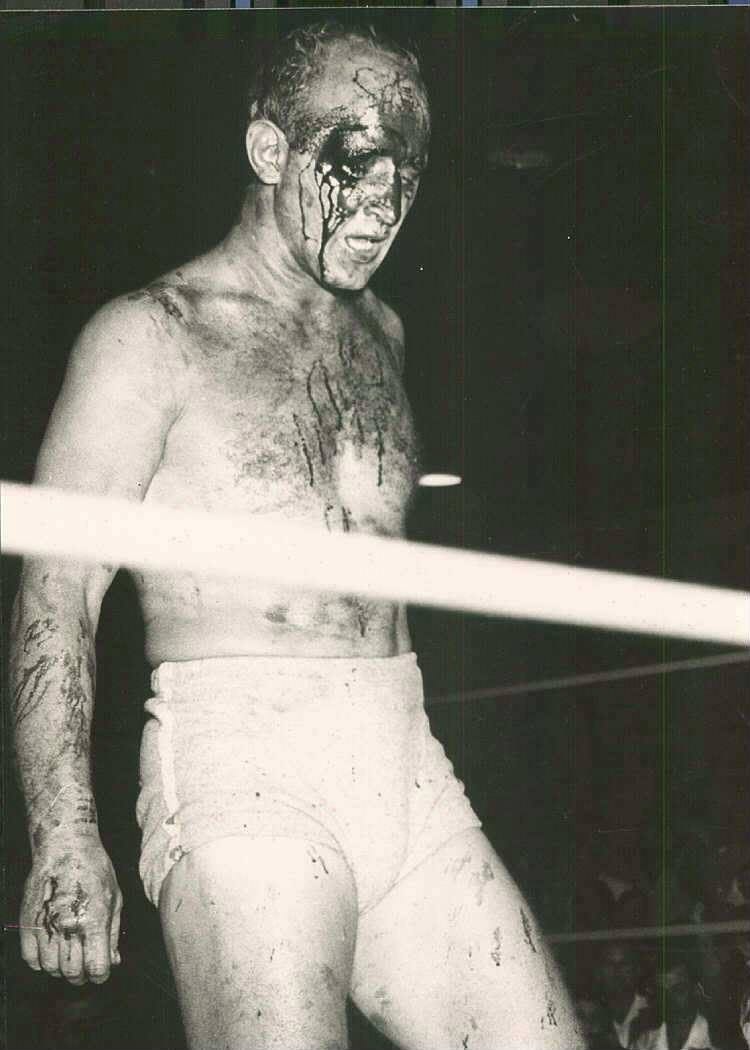

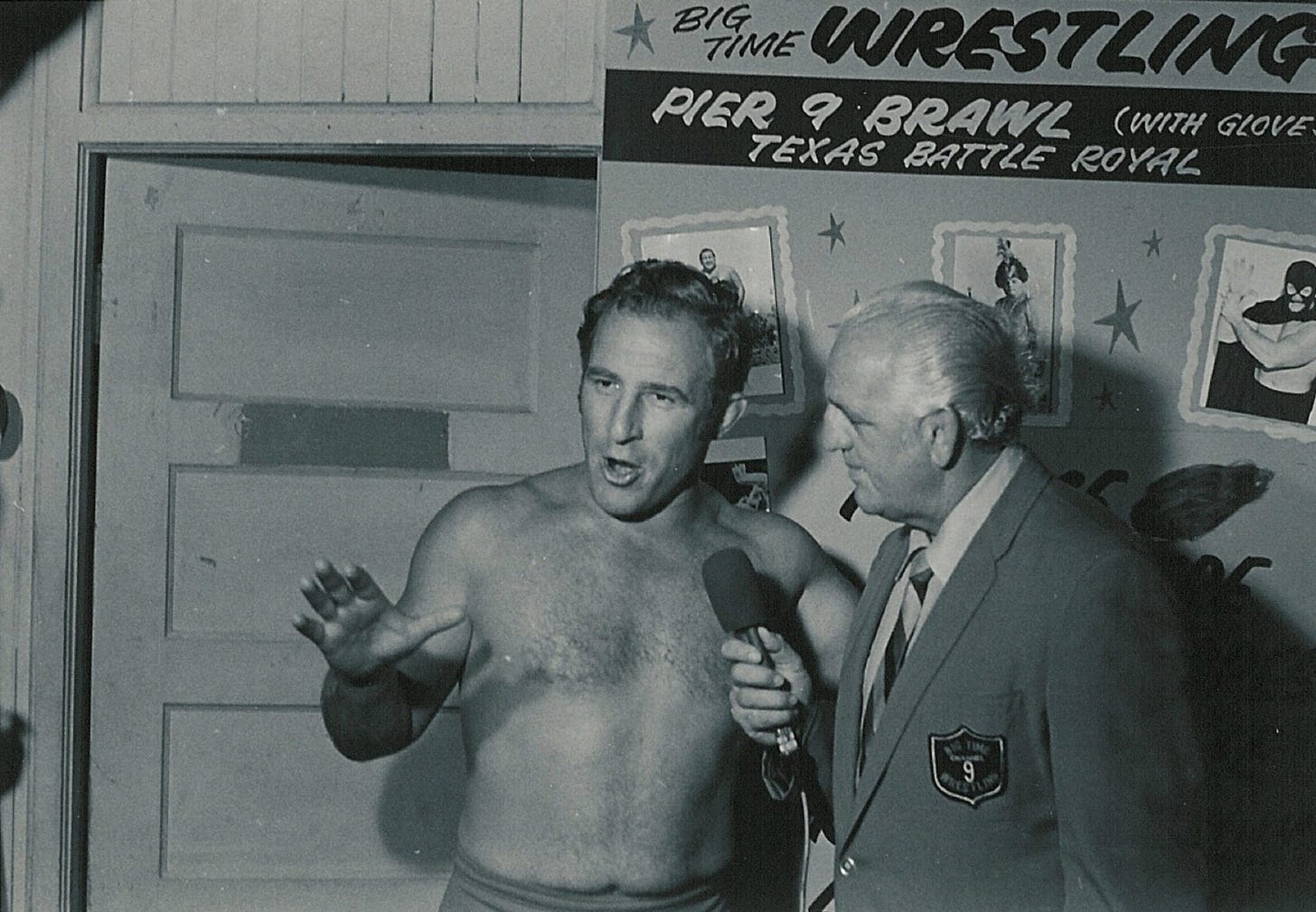

Although Gene LeBell would become best known for his exploits as a wrestler, announcer, and referee at the Olympic Auditorium, it was in the Amarillo, Texas-based Western States Sports Promotion where he first made a name for himself. Owned by former wrestlers Karl “Doc” Sarpolis and Dory Funk Sr., it was one of the most successful leagues in the United States. A master of “blading,” using a concealed razor to cut a fighter’s brow to make him bleed, Sarpolis’s creative fight cards included midget wrestling, cage matches, barbed wire matches, and submission-only jacket matches.

On June 12, 1956, the Amarillo Globe Times announced, “Gene LeBell, 23-year-old athlete from Los Angeles who probably is the greatest judo wrestler ever developed in America, will make his Amarillo debut on Thursday night’s Sports Arena program.” In addition to LeBell’s twenty minute submission “jacket match” against veteran wrestler Martino Angelo, the fight card also featured Big Bob Orton, Tokyo Joe, and midgets Little Beaver, Cowboy Bradley, and Tom Thumb.

During his first week in Texas, Gene LeBell inflamed Texas wrestling fans when he got on television and said, “one Californian can beat any 10 Texans.” After he noticed signs in the wrestling venue that read, “Colored Drinking Fountains” and “Colored Bathrooms,” and realized that the Texans were “very, very prejudiced,” he went one step further. LeBell ventured into the black section of the segregated Amarillo Sports Arena and began to sign autographs. When a five-year-old black girl approached him, he picked her up, hugged her, and the crowd began to boo. Afterwards, when the television commentator chastised the wrestler for giving “a pickaninny” his autograph, LeBell grabbed the man and bellowed, “Look my mammy is black.”

Next, promoter Dory Funk Sr. began to capitalize on the fans’ hatred of Gene LeBell and offered $100 to any audience member, born in Texas, who could beat him. Instantly, there was a line of big cowboys and farmers in ten gallon hats and cowboy boots lining up to fight the bigmouthed, Jewish wrestler from California. After LeBell made fast work of all the challengers by choking them unconscious, the Texan pro wrestlers “would jump in the ring to save the day,” recalled LeBell. “and they'd beat the shit out of me and body slam me and everything.” The crowds grew each week and the challenge matches continued for sixteen straight weeks.

Gene LeBell traveled all over Texas and often wrestled seven nights a week. In order to maximize his ring time, one of the promoters had a one-eyed, masked costume made for him in Mexico, and LeBell fought as “Henry, the one-eyed Batman.” “You’d wrestle in some of the small towns, and then you’d come back and wrestle as another character with a different gimmick,” he said. “and then I'd come back and Gene LeBell was the asshole, with different styles.” “He loves to belittle Texans and his bold confidence could easily be described as arrogance,” wrote the Amarillo Daily News before conceding, “but Gene LeBell, when it comes to judo wrestling, might be rated the best in the profession.”

Throughout his pro wrestling career and his life, it was often hard to distinguish between Gene LeBell the outrageous “heel” pro wrestler and Gene LeBell the disciplined martial artist who was the first American to fight and teach mixed martial arts. Even his older brother, fight promoter Mike LeBell, told Sports Illustrated that he had fired Gene on occasions and “sometimes even I thought he was crazy.” As a result of this confusion, he has never received the long overdue credit he deserves for being America’s first mixed martial arts (MMA) fighter and teacher.

“Too many people think of me only as a Judo expert,” LeBell complained to one Texas reporter prior to his first official MMA fight in Utah, “but I can take care of myself in any ring situation.” Because Gene LeBell grew up boxing, he believed that every serious fighter needed basic boxing skills. However, this did not mean that the grappler had lost faith in his wrestling. Instead, he believed that skill in both disciplines gave him more strategic options and a huge advantage over his opponents. “If I'm going against a champion wrestler, he better be able to block an overhand right,” LeBell explained. “If he's a champion boxer, you tackle him, go behind, and grab a leg, and ankle.” He admitted that he had been kicked out of a lot of gyms over the years, “If I was at a judo school, I’d tackle them or slap them a little ‘accidentally.’ Or in a boxing gym, if a guy started beating me too bad, I’d suplex him. Everything I did was practical. You have to strip things down and get to the practical stuff.”

Gene LeBell did not like rule-and-tradition-bound martial arts. “If I get you in a leg lock, it’s not legal in judo but it works so who cares? I didn’t like it when they brought more rules in—if I can use your hair or your jamoke [penis] as a handle, hey it may not be acceptable but it works.” LeBell’s MMA had little to do with what people consider MMA today; it was much closer to Bruce Lee’s martial art of Jeet Kune Do. After studying Wing Tsun Kung Fu in Hong Kong with the legendary Yip Man, Lee sought to free himself from what he described as “the classical mess” of traditional Asian martial arts. Lee began to study other martial arts like boxing, Muay Thai, Savate, and fencing. He cherry-picked the best techniques from each art, then combined them into a practical, real life fighting system called Jeet Kune Do. Although Gene LeBell and Bruce Lee shared the same “if it works use it” mentality, the American was doing this decades before Lee, and at a much higher level. Unlike Lee who never competed, LeBell had competed and won at a world class level in both judo and wrestling and was also a skilled amateur boxer.

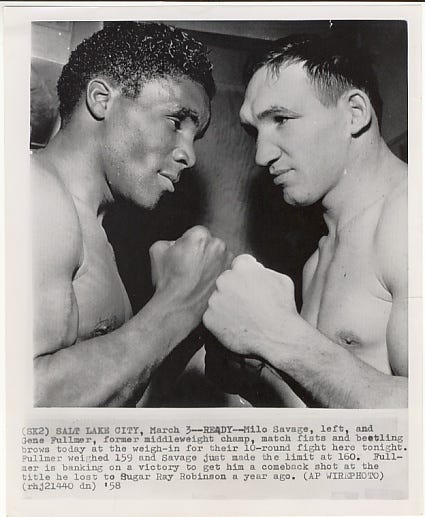

Gene LeBell, his manager, and Judo teacher arrived in Salt Lake City in December 1963 for his fight with amateur boxer Jim Beck, the man who issued the $1000 challenge in his Rogue Magazine article, “The Judo Bums.” When they met with the fight promoter, he informed them that LeBell was not fighting Beck, but pro boxer Milo Savage instead. “They brought in a ringer,” he recalled. “Savage had gotten a lot of attention for busting a local karate instructor’s jaw so they thought he could take me out without breaking a sweat.” Born in 1924, George Jethro Ware fought under the name of “Milo Savage” and had been fighting pro since 1946. A top middleweight during the 1950s, Savage lost two close decisions to middleweight world champ Gene Fullmer.

The day before the fight, Gene LeBell sat down for a prefight interview at a local television station. When the hostile interviewer asked him how he planned to win, the pro wrestler slipped into “heel” mode. “I'm going to strike him, freeze his body and hammer him into the ground,” he said. “I'll leave him in the ground until summer, defrost him and pull him out, then choke him out.” The skeptical TV host told LeBell that chokes don’t work, then compounded his error by inviting him to try to choke him. Before he even knew what happened, the grappler “snatched him, choked him out, and dropped him on his head.” With the commentator now sleeping soundly on the floor, LeBell picked up the mic and announced: “Our commentator went to sleep. I guess he’s quitting. Now it’s the Gene LeBell Show! Come to the arena tomorrow night and watch me annihilate, mutilate and assassinate your local hero because one martial artist can beat any 10 boxers.”

At the prefight rules meeting, Gene LeBell pulled out his instructional book on judo and pointed to a photo. “Can I pick him up over my head like this?” he asked. Then he put both hands over his own throat and began to pantomime the choking motions, “Can I choke him?” By the end of the rules meeting, Savage’s handlers were laughing at what they now thought was a red haired buffoon. In the end, the fighters agreed to fight five, three-minute rounds. Savage was allowed to punch, but LeBell was relegated to only Judo holds, and throws, and he was not allowed to kick.

On December 2, 1963, Gene LeBell and Milo Savage squared off in front of a sold out crowd at the Salt Lake City Auditorium, and thousands more watched America’s first MMA fight on television. Because Savage fought out of Salt Lake City, he had a decided home court advantage, and the very partisan crowd included Salt Lake City resident and former world middleweight champ Gene Fulmer. While Gene LeBell wore his full Judo Gi, Milo Savage wore a thin karate Gi, that his cornerman had smeared with Vaseline, and boxing trunks. Instead of boxing gloves, Savage wore fingerless, 4-ounce speed bag gloves that LeBell and his cornerman (judo blackbelt and future California superior court judge, Dewey Lawes Falcone) claimed had a “metal or plastic plate under the leather running from the knuckles to the wrist and the tip of the thumb.”

When the bell rang, it was clear that the boxer had done his homework. He was careful to throw only jabs and fast, controlled punches. Towards the end of the first round, Gene LeBell got Savage in a clinch, but aggravated an old shoulder injury in the process.

The two men fought the next two rounds cautiously. The injured wrestler avoided most of the boxer’s punches, and the boxer did not allow himself to get taken to the ground. Finally, in the fourth round, Gene LeBell parried a Savage left, ducked under a powerful right, drove the boxer into the ropes, then threw him, and landed with all of his weight. Next, the wrestler took the boxer’s back, and when he began to choke him, Savage bit his finger and LeBell said, “Milo, you bite my finger, I’m going to take your eye out.”