“Who is the most beautiful man in the world?” The red-haired gargoyle screamed inches from my face.

When I did not answer, his freckled hand, thick as a catcher’s mitt, slowly pulled the back of my neck forward like a sadistic chiropractor. First, the vertebrae in my neck began to crack, but when the pressure spread to my spine I feared that something was about to break and said, “You, Gene!” Although this was the first time I had met Gene LeBell, I had known him my entire life.

Like many of my Southern California peers in the 70s, my parents divorced when I was young, and both worked long hours at their respective careers. Most nights, after dinner, my sister and I posted up in front of the Sony Trinitron to watch “The Brady Bunch,” “The Partridge Family,” “Dragnet,” or “Adam 12.” If I was good, our babysitter would let me stay up and watch a weekly physical morality play. Each episode began with announcer Jimmy Lennon’s ritual incantation, “Week after week, the crowds are bigger, the wrestling is greater, at the Olympic Auditorium. Make your plans to be here, but phone for reservations—RICHMOND 9-5171.”

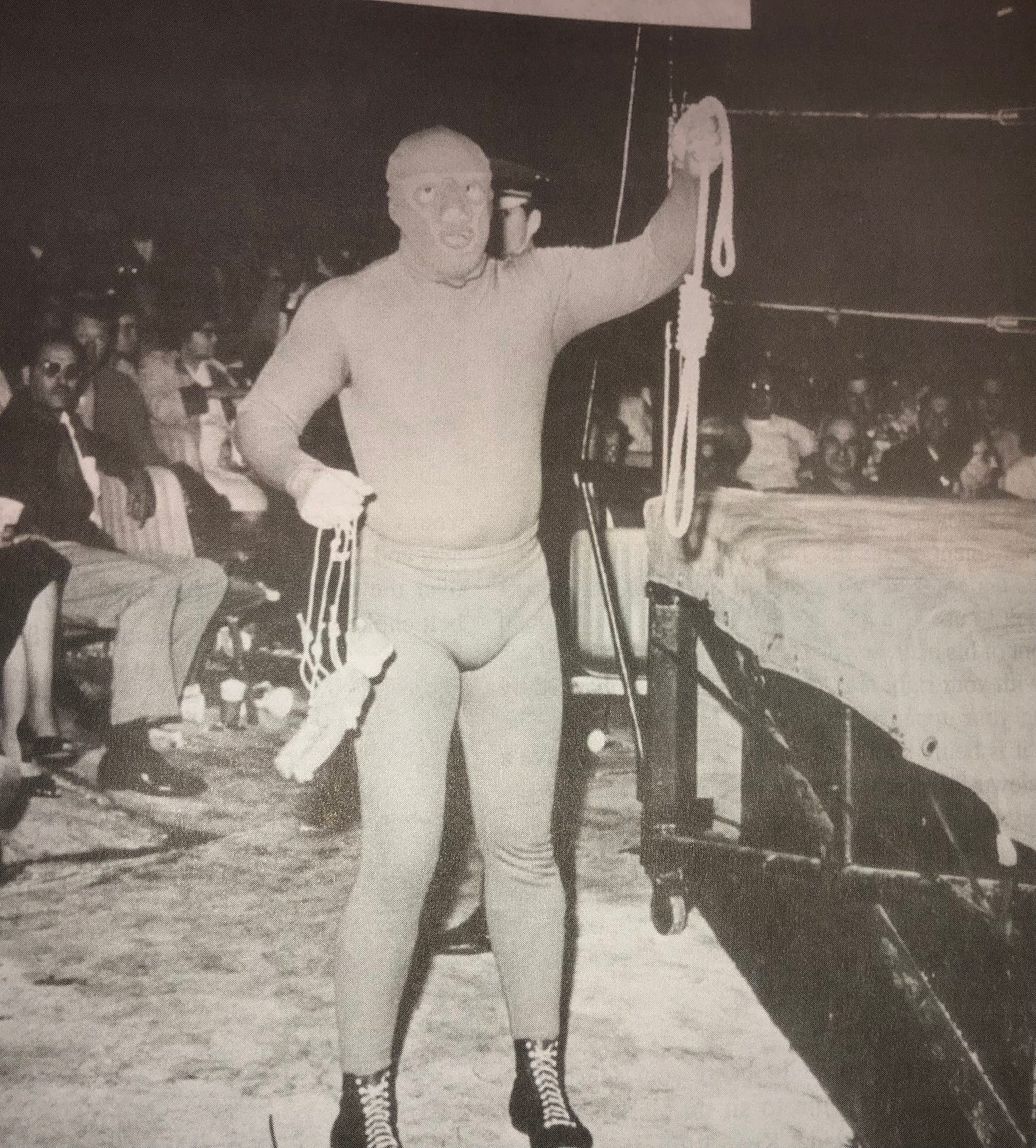

My heroes—Chavo Guerro, John “The Golden Greek” Tolos, and Mil “Man of A Thousand Masks” Mascaras—faced off in “Texas Death,” “Loser Leaves Town,” “Battle Royale,” cage, and tag team matches, against villains like “Classy” Freddie Blassie, “Rowdy” Roddy Piper, and George “The Animal” Steele. There was one wrestler, however, who scared me more than any other. Clad in a full body suit that covered everything but his eyes and nostrils, “Hank the Hangman from Bounty Hunter Gulch” would limp into the ring holding a noose in one hand and a voodoo doll in the other. First, he would torment the crowd, then he’d attack his opponent before the bell had rung when his back was turned. Little did I know that “The Hangman” was none other than Gene LeBell.

On August 9, 2022, Gene LeBell died at his home in Sherman Oaks, California. Although the Judo champion, professional wrestler, and mixed martial arts pioneer appeared in more than one thousand movies and television shows during his career as a stuntman, he was probably best known for “allegedly” choking Steven Segal unconscious on the set of his movie “Out For Justice.” LeBell also provided the inspiration for Brad Pitt’s character “Cliff Booth” in Quentin Tarantino’s “Once Upon A Time in Hollywood.” The film’s depiction of the grappler’s “attitude adjustment” of Bruce Lee was as insulting as it was inaccurate. It would take a Raymond Chandler, or a John Fante, not a Hollywood filmmaker who has never set foot on a mat or stepped into the ring, to do justice to the remarkable story of this native Angeleno.

The second son of Maurice and Eileen LeBell was born into affluence in Los Angeles in 1932. The couple married after they graduated from Los Angeles High School. Maurice became an osteopath and Eileen work in a law office and studied law. Gene was just a small boy when a family beach outing went horribly wrong and Maurice LeBell was paralyzed, and later died, from a surfing accident.

Now that Eileen LeBell had to support two young boys, she made a deal with a San Luis Obispo boarding school called the California Military Academy. In exchange for Gene’s and his older brother Mike’s room, board, and tuition, she took over the academy's advertising. Next, Mrs. LeBell got the advertising contract for Los Angeles Athletic Club (LAAC), owners of the Olympic Auditorium. The promoter who was leasing the auditorium was not making money, so the LAAC put her in charge of the auditorium’s business management, and she hired her future husband, Cal Eaton, a California State Athletic Commission inspector, to handle fight promotions. Under LeBell, Eaton, and matchmaker Babe McCoy (who was banned from boxing for life for fight-fixing in 1956), the Olympic’s boxing take jumped from an average of $900-$1200 a show to $11,000 a show.

Known behind her back as “Madame Nhu,” “The Dragon Lady,” “Ma Barker,” or “The Man-Eating Lotus Flower,” Eileen LeBell Eaton grew into one of America’s savviest boxing and wrestling promoters, and she was the first woman inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame. Turning the Olympic Auditorium into a world class boxing and wrestling venue was no small feat due to the large role played by organized crime in Southern California’s fight game. Gangster Mickey Cohen sold candy at the Olympic as a kid, fought professionally there as a young man, and when he was not in prison, could be found in the auditorium’s “gambler’s section” on most fight nights.

Now without a father, Gene LeBell sought and found a remarkable series of male role models, and was, quite literally, raised by wolves. He met the first one when he was seven and his busy mother sent him to the LA Athletic Club to get him out of her hair. When the boy saw a group of extremely fit men with bent noses and cauliflower ears, he walked up to them and declared, “I want to be a wrestler.” “What do you want to learn? Boxing, Greco-Roman, freestyle, Savate or grappling?” replied the legendary Ed “Strangler” Lewis. “What’s grappling?” asked the boy. “That’s a combination of all of them,” he explained, “You can hit ’em, eye gouge ’em.'” The seven-year-old was sold and from that day forward considered himself “a grappling man.”

Dubbed “The Strangler” after choking an opponent unconscious with a sleeper hold, the 5’10,” 265-pound Lewis had been wrestling professionally since 1905 and had become a household name in the 1920s when he provided the muscle for “the Gold Dust Trio.” His manager Billy Sandow and wrestler/promoter Joseph “Toots” Mondt were among the first to add story lines, hero and heel characters to pro wrestling. The trio played a large role in transforming the sport into the dramatic physical spectacle that it is today. Although many of the matches were as fixed then as they are now, wrestlers like Lewis and his protégé Lou Thesz were incredibly skilled fighters because they learned their trade as “catch wrestlers.”

During the 19th and early 20th century, American carnivals featured “athletic shows” in which spectators, incentivized by cash prizes, could fight the carnival’s resident wrestler or strongman. These matches were not rigged, they were “shoots,” a carny term for real, unscripted fights. Because the catch wrestlers faced local toughs—cowboys, farmers, fishermen, loggers—in each and every town, they tried to win their matches as quickly as possible by using “hooks” or technical submission moves like chokes, joint locks, and neck cranks that were and are illegal in amateur wrestling. Legendary “shooters” like “Farmer Burns,” “Strangler Lewis,” Lou Thesz, and Karl Gotch came of age in this environment and kept these techniques and traditions alive.

While professional wrestling matches in the post World War II era were “works” (fixed fights), wrestlers were always careful to maintain “kayfabe,” code for believability in the ring. They tried to keep the fact that the fight’s outcome was prearranged and that the animosities were not real, an inside secret. Wrestlers, unlike actors, have to remain “in character” both in and out of the ring in order to maintain their illusion.

When Gene LeBell returned to the California Military Academy after his encounter with the pro wrestlers, he put his new grappling skills to work on a cadet who had been bullying him. After he choked the student unconscious, LeBell hid in the school’s stables where the old Cossack who took care of the academy’s horses found him. Instead of turning him in, the precocious, red-haired boy, who had already been labeled a troublemaker, found another mentor who taught him how to ride, train, groom and understand horses.

The LeBell brothers spent all of their summer vacations and school holidays in Los Angeles and began working at the Olympic Auditorium when they were very young. Gene climbed scaffoldings and changed light bulbs, mopped floors, sold refreshments, and met more wolflike male role models like gangster Mickey Cohen, matchmaker Babe McCoy, wrestler Gorgeous George, and countless bookies, gamblers, and standover men. Whenever Mickey Cohen saw LeBell at the fights, he bought “the kid” candy and hotdogs. “Mickey’s bodyguards weren’t very subtle,” he recalled, “their jackets would sometimes fall open to reveal big pistols holstered under their arms.” The gangster once made a hot dog vendor put two hot dogs in one bun for the boy, paid the man with a five-dollar bill, and told him to keep the change. Although he always got his hot dogs for free because his mother ran the auditorium, Gene said nothing, “I didn’t want to cost the hot dog guy a big tip.” He was not yet a teenager, but “the kid” was growing up fast.

By 12, Gene LeBell was cross-training in boxing and drove his scooter from the Olympic to The Main Street Gym (where many of the gym scenes in “Rocky” were shot). Opened in 1933 and located in downtown LA’s Skid Row, the Main Street Gym was the West Coast’s equivalent of New York’s Gleason’s Gym.

While Jack Dempsey, Rocky Marciano, and Sugar Ray Robinson trained on the heavy bags and sparred in the ring, men in derbies smoked big cigars, and discussed the Olympic’s next fight card with owner Howie Steindler (Burgess Meredith’s character “Mickey” in “Rocky” was based on Steindler), who ran the gym with an iron fist (his 1977 murder remains unsolved). “I was a young kid at Main Street Gym and Sugar Ray Robinson came in with his hair greased down and he looked beautiful, he had his initials on his Cadillac. He got in the ring and his sparring partner didn’t show up,” said LeBell, “Howie Stein says, ‘Anyone want to work out with the Sugarman?’ And I says, ‘Ya, if he isn’t afraid of me.’ In other words, if your head is this big [holds his hands far apart] no good boxer is going to miss it. In the first round, he hit me 300 times. He taught me a couple of things.”

After losing a fight to a smaller boy who knew Judo, Gene LeBell next began to train in Judo with his typical, single-minded zeal. First he trained with Larry Coughran and Jack Sergil, then Coughran sent LeBell to Tadasu Iida and Tusuke Hagio at the Hollywood Dojo where only Japanese was spoken. Many of LeBell’s classmates had spent World War II in Japanese internment camps and took out their frustrations on the teen. “Gene experienced an enormous amount of racism throughout his career. He was a real ground breaker in so many ways,” said AnnMaria De Mars, the first American to win a gold medal in a world Judo Championship, and fighter Ronda Rousey’s mother, “Here comes in this big white guy, red hair, obviously not Japanese, and he wants to learn their thing, and a lot of people just said, ‘Go away.’…Even the ones that let him work out, just tried to beat the crap out of him.”

Like Bruce Lee, one of Gene LeBell’s greatest strengths as a martial artist was his ability to see the similarities between the different martial arts, take what was useful, and throw away the rest. Just because he was wearing a Gi and doing Judo, much to the chagrin of his opponents, he also used techniques that he had learned from the pro wrestlers. “A lot of the moves that I learned from the pros were pretty much the same moves in Judo but I was learning variations,” he wrote, “There’s a lot of different ways to do a hip lock for example, and the pros showed me a lot of ways of applying moves that my Judo opponents weren’t ready for.” When LeBell entered his first Judo tournament, the skinny, fourteen-year-old greenbelt was disqualified for cranking opponents’ necks and knocking the wind out of them with his throws.

Gene LeBell’s martial arts progress ground to a halt when he was hospitalized for anemia. He was in bed at Cedar Sinai Hospital when he learned that Mickey Cohen had been shot outside of an after hours club on the Sunset Strip and was in a guarded room in the same hospital. He walked to his friend’s room in his underwear. The cop guarding the door would not let him in the room, but the gangster’s bodyguards greeted the teenager warmly and ushered him in. “There was Mickey Cohen,” said LeBell, “buckshot wounds red with blood through the bandages and he says, ‘I hear you don’t feel so well kid. Anything I can do?’”

After Gene LeBell was discharged from the hospital he became a physical fitness fanatic in an effort to rebuild his atrophied body. His daily regimen included medicine ball training, 500 sit ups, 500 push ups, and 1000 jumping jacks. Eager to push himself even further, LeBell was constantly searching for bigger, tougher training partners. Prior to the 1954 AAU national Judo championship in San Francisco, his mother suggest that he go to Hollywood Legion Stadium and train with the pro wrestlers there. “The wrestlers were from the old time shooter and hooker tradition and each and every one of them could really wrestle,” said LeBell, “and by wrestling I mean grappling.”

His new training partners, Vic and Ted Christy, Lou Thesz, and Karl Gotch, had bottomless arsenals of legal and illegal wrestling techniques. “Lou [Thesz] showed me more finishing holds than any of my teachers,” recalled LeBell, “Lou Thesz was my mentor and when I was a kid he’d tell me where to go, who to train with so they could beat the living tar out of me.” In addition to techniques, Thesz encouraged his student to be merciless on the mat, “Thesz told me life is grappling. You’re in competition with everybody. If you fight for a living you can’t give a damn about the opponent because they’re trying to take food out of your mouth and your kids’ mouths.”

The wrestler who probably had the biggest impact on Gene LeBell was Karl Gotch. The former member of the Belgian Olympic wrestling team who was now wrestling professionally said, “I only put on pajamas when I go to bed,” when LeBell stepped onto the mat in his Gi. Gotch destroyed all comers and impressed LeBell with both his skill and brutality. “I saw him get hold of Olympic wrestlers and just gobble them up with front facelocks, choke them out, or break an ankle.” “When he [LeBell] was with me, he changed his ideas pretty fuckin’ fast,” said Gotch. “I’ve seen Gotch hurt a lot of people in the ring and I used to just watch him. ‘Here’s a guy I don’t like.’ He’d just have them for lunch, which I thought was kind of entertaining ’cause my elevator didn’t go to the top, so I was in good company. The holds he did were practical, devastating and sadistic.”

It was Karl Gotch who explained to LeBell that it was not enough to defeat your opponent, you had to punish them for having the temerity to step into the ring with you. If they got injured, so be it. “I’ve got to give him [LeBell] credit for one thing,” said Gotch, “he had guts!” “Sadistic Bastards can really take care of themselves, and there were only a few of ’em, including Karl Gotch, Lou Thesz, Vic Christy, and me,” said LeBell, “Karl Gotch was my favorite because he promoted me to Sadistic Bastard.” More than his black belts, trophies, or titles, the martial arts accomplishment Gene LeBell was proudest of was the title “Sadistic Bastard” that Karl Gotch bestowed upon him.

Combining the submission wrestling techniques he learned from the pro wrestlers with Judo, not only did one-hundred-sixty-three-pound LeBell win the 1954 AAU Judo championship in his weight division, he won the grand championship against the winners of all the other divisions. “The professional wrestlers helped me with Judo because what is called an uchi mata in Judo is called a whizzer in wrestling,” wrote LeBell, “All of the Japanese techniques that were said to be invented by Jigoro Kano in 1882 were used centuries before that in pro wrestling only with different names and instead of a gi, they wore wrestling attire.”

After his victories, Gene LeBell told his fight promoter stepfather, Cal Eaton, that he now wanted to wrestle professionally. Eaton laughed, then named a fifty-year-old pro wrestler and bet him $100 that the old pro wrestler could beat him five times in five minutes. LeBell accepted the bet and when he showed up at the Hollywood Legion Auditorium for his match, the wrestler turned to Eaton and told him to save his money and called off the bout. Gene LeBell again won his weight division and the unlimited division of the 1955 AAU Judo championship, then he traveled to Japan. The first Gaijin to compete in a Judo event in the post- war era, LeBell won eighteen matches in two days.

With nothing left to win in Judo, much to the dismay of the Judo establishment, Gene LeBell began to wrestle professionally. One day a wrestler, who also worked as a stuntman, got him a part in “The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet” and he received his Screen Actors Guild card in 1955 after playing a bully who gets thrown into a wall at a high school dance. “Ozzie was such a considerate person,” said LeBell, “In addition to caring physically, he also taught me about contracts and residuals. That education made me a lot of money in the long run.”

Gene LeBell showed up in his Gi to audition for the Superman television show. He did a few dramatic falls when Superman himself, George Reeve, announced, “That’s it. He’s our guy. Tell everyone else to go home.” Playing the role of the evil Mr. Kryptonite, LeBell did numerous live appearances at theatres and television stations with Reeve who he called “the kindest man I ever knew.”

Next, he appeared on the Jack Benny Show in 1960 and got beaten up by the septuagenarian comedian. “I liked him right away. Guys like Jack Benny were human beings who brought a sense of humor to the job with them.” LeBell also took smaller, stranger jobs like wrestling a bear named Victor at supermarket openings. “Victor was a sweatheart. Wrestling him at supermarket openings, then later for movie stunts was great for my Judo,” said LeBell, “If you can get used to being grabbed by a 700-pound bear, then a human wasn’t much of a challenge.”

Not everyone was happy with Gene LeBell’s career decisions. His local Judo dojo kicked him out of their school because he was doing stunt work in the movies. “I was shaming Kodokan Judo. Kodokan Judo is very good, but the movies made money,” said LeBell, “When I did Judo, I’d win all my matches. When I did movies, stunt work, I lost all my matches. Now you look at those pieces of tin up there, gold plated, that’s from winning. You look at my bank book, that’s from losing. What would you rather own? A bunch of trophies or enough money to go out and buy a car cash?”

Even after he began his career as a stunt man, Gene LeBell continued to wrestle professionally and by the 1960s, he wore many hats at the Olympic Auditorium. He wrestled, refereed, and conducted locker room interviews. “When the family needed an enforcer to step into the ring with a wrestler who didn’t want to go along with the program,” said professional wrestling icon “Classy” Freddie Blassie, “all they had to do was open Gene’s bedroom door and tell him to get into his wrestling gear.”

Gene LeBell also worked as plainclothes security at the Olympic at the often unruly boxing matches. Every time the auditorium’s head of security, policeman Tom Cornwell, threw someone out, he followed them out to make sure that nobody else got involved. One night, Cornwell was escorting a big guy to the exit and he punched him in the face and knocked out the policeman’s front teeth. LeBell hustled the perpetrator to a nearby office and when the police came into the office to arrest the man, he was unconscious, and now missing his front teeth. “I think he drank too much and fainted,” said LeBell.

By now, everyone gave Gene LeBell a very wide berth. He was a very dangerous man who was not to be trifled with or disrespected. “In Texas I hurt a guy,” said LeBell, “and I had to leave town, you might say.” LeBell had recently married and another wrestler “grabbed my wife by the ass.” When the pair met in the ring, “I fucked him up. What can I tell ya?” recalled LeBell, “payback’s a bitch.”

In 1963, an article entitled “Judo Bums” appeared in Rogue Magazine. In it, writer and boxer Jim Beck called Judo players, and more generally, Asian martial arts, complete frauds. “Every Judo man I’ve ever met, was a braggart and a show off,” he wrote and then issued a challenge. “Judo bums, hear me one and all! It is one thing to fracture pine boards, bricks and assorted inanimate objects, but quite another to climb into a ring with a trained and less cooperative target. My money is ready. Where are the takers?” Incensed by this blanket dismissal of martial arts, Hawaiian Kenpo karate pioneer Ed Parker showed up where Gene LeBell was training in Hollywood and asked him to take the fight.

LeBell asked Parker why he chose him and he said, “Gene you are the most sadistic bastard in the world.” Because they could not sanction a fight like this in California, the bout would be held in Salt Lake City on December 2, 1963. The grappler arrived at the Fair Ground Coliseum in Salt Lake City and learned that his opponent was not amateur boxer Dave Beck. Instead he would be fighting Milo Savage, the former number five ranked light heavyweight in the world. “It sounds like I’m blowing my own horn, and I don’t mean to—I represented all the martial arts,” said LeBell, “I never said one art is better than the others. They’re all good. You should learn everything. You’re not a complete martial artist unless you do everything.”

Read Part Two of Gene LeBell’s story here.

Wonderful story, Peter. As an aside, my sister was a Nurse in NYC and Jack Dempsey was a patient on her floor for several weeks. Despite his failing health he was charming, sweet and wanted to talk. His hands were still the size of a large ham, his ears were misshapen and his body crumbling but he always greeted her w/ a smile. Dempsey grew up in a different time than La Bell but you'd have to figure he was as much street fighter as boxer, certainly growing up. The human side of the pugilist and grappler, at least the ones from many years past, is always interesting to learn about. Looking forward to Part 2.